The “Eureka!” moment when you come up with a fabulous idea to implement at your museum is a great one, but it is also sometimes accompanied by trepidation: What if visitors don’t respond to the idea? How can I get my colleagues on board? Will this idea really help push my institution forward?

At these moments, visitor studies can be a crucial resource in refining the initial concept and turning it into something that is truly audience-centered. Visitor studies, a set of research and evaluation activities designed to elicit feedback from attendees of informal learning centers, can take on many forms and occur at many different times in the project life cycle. But, while I have a fondness for visitor research at any stage, there is a special place in my heart for front-end research.

What is front-end research?

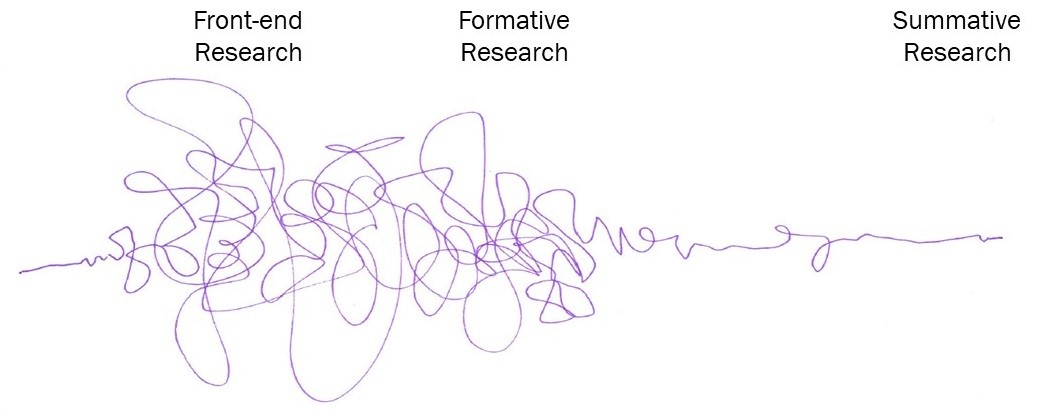

At the Cleveland Museum of Art, we typically conduct visitor studies at one of three different stages in the project life cycle. One way to think about a project is by the path it takes from the initial concept until it’s complete.

While the concept may start off simple, there’s often a lot of activity and change that takes place between the initial idea and the completed project. As the project evolves, it’s important to keep your audience front-of-mind. To that end, visitor feedback can be gathered at several points along the project life cycle:

- Front-end research: Done in the early stages of a project, this highly exploratory research focuses on gathering feedback from visitors before major decisions are made about a project.

- Formative research: Once some of the major ideas of the project have been finalized, research done during the formative stage is often focused on gathering feedback on specific elements, such as testing a prototype of a new interactive game.

- Summative research: Completed at the end of a project, research at this stage focuses on assessing the project’s outcomes and how effective it is at achieving specific goals.

Front-end research for audience growth

At the Cleveland Museum of Art, we use front-end research to inform a variety of projects. One case where we often use it is during the planning process for special exhibitions. During this planning, our primary goal is to gather information that will allow staff—particularly those from our curatorial, interpretation, and marketing departments—to run some concepts by potential visitors to the exhibition and learn where the opportunities and barriers might be in engaging them. We design research projects around key questions which can generate data applicable to multiple departments, to ensure that we get the most information possible for the greatest number of staff. For example, we might ask what potential visitors do and do not know about the themes explored in an exhibition, which helps curatorial and education staff develop interpretive elements, and also provides insights for marketing to use when developing messaging and talking points around the exhibition.

Our front-end exhibition research projects tend to be qualitative, as we seek to encourage deep discussion amongst participants and gather their wide-ranging feedback. Typically, these projects are focus groups comprised of participants who meet either specific demographic or psychographic criteria, and we aim to conduct the groups approximately ten to twelve months before the exhibition opens so visitor feedback can be incorporated into planning. For big projects, we work with an outside firm to recruit participants; but for projects with smaller budgets, we post screener surveys on social media, comprised of questions about visitation frequency, demographics, and time availability, and then contact relevant potential participants to come to a discussion held on-site.

In designing front-end focus groups for the exhibition The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s, the CMA Research and Evaluation team worked with curators from CMA and Cooper Hewitt, as well as CMA education and marketing staff, to determine the key questions that they were grappling with when thinking about the next steps for the exhibition. From there, an external firm recruited focus groups comprised of both members and non-members who visit less frequently but attend other local arts and culture attractions.

During our focus groups, participants discuss their overall impressions and associations with the CMA before delving into topics directly related to the exhibition at hand, such as key themes and ideas, terminology or relevant historical events, images of objects that would be featured in the show, possible titles and program ideas, and advertising mock-ups. For the The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s project, staff working on the exhibition’s planning were able to watch the focus groups from behind a one-way mirror so they could hear the feedback directly, which the research team has found can cultivate buy-in on a research project. The curators found learning about visitor perceptions and biases around historical terms, such as “art deco” and “Jazz Age,” particularly helpful. While this feedback didn’t change what was included in the exhibition, it provided a key baseline for understanding how to interpret them in the exhibition, and for deciding what images to feature in marketing collateral. Once the exhibition was on view at the CMA, the team conducted a summative evaluation and found some of the highest visitor satisfaction levels ever recorded for a ticketed special exhibition, with a Net Promoter Score of 90 and 54 percent of visitors rating their experience as “Superior” on the Overall Experience Rating (OER).

Front-end research can also be a great tool to use with broader strategic initiatives, such as new marketing campaigns. In planning an institution-wide marketing campaign, the CMA used focus groups, interviews, and surveys to understand motivations for institution-wide target audiences, including young professionals and parents and guardians of children. These discussions revealed key insights on which groups are the most likely to be interested in attending CMA, what barriers have the most impact on attendance, and what perceptions—both correct and incorrect—people have about the museum. Gathering this information early in the process allowed us to build the campaign around these key insights, saving resources and effort along the way. The “Must CMA” campaign, refined with this feedback, has resulted in positive attendance outcomes for the museum.

Conclusion

Front-end research activities are an important way to bring in new voices, allowing for more perspectives to be heard and incorporated into planning. Whether it’s feedback from your core audience or people who have never stepped into your museum, front-end research is a critical tool to have in your planning toolbox. While it may sometimes feel like yet another step in an already complex process of turning an idea into reality, we have found that adding front-end research to the mix can actually save time and resources, by homing in on the aspects that are most critical to making a project a success.

About the author:

Elizabeth Bolander is the Director of Audience Insights and Services at the Cleveland Museum of Art and President of the Visitor Studies Association.