Developing an exhibition on the many faces of identity unmasks the slippery nature of truths and beliefs about gender.

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2020 issue of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

At the Exploratorium in San Francisco, interactive inquiry-based experiences exploring a variety of phenomena are central to all of our museum offerings. Within the context of exhibition planning, individual exhibit development is often driven by the interests and passions of individual team members. This was the case with “Self, Made: Exploring You in a World of We,” an interactive exhibition that examined the topic of identity that ran in the summer of 2019.

Throughout the exhibition development process, we were sensitive to and worried about how exhibits that challenged visitors’ ideas of race and gender might impact them. But going into the process, we didn’t realize how developing these exhibits would challenge us and illuminate our own diverse experiences and perspectives. Ultimately, this exhibition was as rewarding for our museum and its staff as we set out to make it for our visitors, and the work continues to inform our active institutional dialogue around inclusion practices.

Designed with families in mind, “Self, Made” included a mix of films, artworks, and artifacts alongside our typical stand-alone interactive exhibits. The exhibition offered ways to explore how identity is constructed personally, socially, and structurally. Four guest curators with diverse backgrounds offered outside advice and contributions. Elements ranged from challenging to expansive and joyful.

While developing the exhibition, the team often spontaneously engaged in conversations about identity and equity, developing activities for each other about race, gender, and privilege that informed our work. We wanted visitors to actively question their ideas about people different from themselves and question the source of those beliefs—so we began to practice this ourselves.

Prototyping Gender

When staff members had previously confronted hard subjects like race, skin color, and privilege, they had navigated challenging conversations with each other. Gender proved no different.

One team member shared that she is raising a child who identifies as non-binary. A former women’s studies minor, she was surprised when her child said to her, “Mom, your ideas about gender are so stereotypical.” She shared her own learning journey, and from this authentic personal experience, we began our research and prototyping on the topic. Concurrently, other staff members were conducting their own experiment with the phenomenon of socialized gender in a museum setting (see “Bathroom Boundaries,” below).

The first prototype to emerge was intended to illuminate and playfully complicate the powerful urge to “decide” gender from surface cues when encountering someone. Inspired by a kids’ mix-and-match flip book, this gender blender offered ways to creatively combine a variety of animal heads with an equal number of torsos and legs in a range of clothing normative to ideas of male and female. The urge to assign gender quickly becomes obvious when the available signals of heads, legs, and clothing are mixed or ambiguous. Choosing to use animal heads disarmed expectations for matching faces to clothing.

But was asking visitors to question gender assumptions that played with surface cues commonly associated with normative male/female clothing enough? Our adviser and guest curator, Ramzi Fawaz, a scholar of queer and feminist studies, pressed us to offer visitors a more expanded view of gender that clearly decoupled gender from sex and included a way to explore queer, fluid, and emerging identities. He challenged us to present gender as the evolving, growing network it is today.

At first, this felt like a daunting task. But research uncovered Sam Killerman’s “Genderbread Person,” which offers a model that not only clearly separates gender from sexual orientation, but also introduces a multitude of gendered experiences in a range of male/female flavors. We began experimenting with the language and modalities to help communicate the differences between sex and gender, between a gendered body and a gendered expression.

In attempting this, we saw how everyone experiences gender differently. The many fraught conversations among team members were a sign of the topic’s heft. We realized the importance of peeling apart gender for our visitors—separating body, identity, and expression into three distinct and variable parts of a person’s gender experience. But would this approach be perceived as too facile or frivolous by those who struggle with forms of gender oppression daily?

Exposing the Layers

Another important discovery from our gender research was the book Who Are You? The Kid’s Guide to Gender Identity by Brook Pessin-Whedbee. Simply and clearly, this book portrays gender as the complicated, layered personal experience that it is. Designed for young children, Who Are You? offered clues to clear and inclusive language. The author provides an interactive wheel in the back of the book that allows children to mix and match aspects of identity expression. This resource inspired the next gender prototype that would become part of the exhibition.

Though our version of the gender wheel was inspired by the book, its design was ultimately driven by our overwhelming desire to expose visitors to the broadest range of gender options beyond male/female. The prototype we created includes four stacked discs that can be individually rotated to select your word of choice. The beginning of the phrase is matched with one of the many word choices available from the disc below. For example, “I am . . .” aligns with options like female, trans, gender fluid, non-binary, or just me. “I love . . .” has options like sewing, animals, dancing, and more. In completing each phrase, visitors are invited to consider gender as more than one part of themselves.

The centermost ring asks each visitor to think about their body (“I have . . .”). This ring had the fewest choices, and we struggled to reach consensus on the options to offer. After much debate and outside guidance, we landed on the following: “a body that makes people guess boy,” “a body that makes people guess girl,” “a body I am comfortable in,” and “a body I am not comfortable in.”

We wrestled with the responsibility to communicate clearly while potentially introducing unfamiliar words—often with fluid meanings—like “tomboy,” “genderqueer,” and “trans.” We knew what we were doing was hard and risky. With each new prototype, someone on the team became concerned that we might neglect to represent options that aligned to a visitor’s experience, causing them harm. Each version revealed the limits of language.

But a trans colleague encouraged and reminded us, “Gender is complicated and discordant, and we don’t have all of the language we need to address it. If all I cared about was you calling me he and him, I’d have a much easier life, as would my trans brothers and sisters.”

We were not prepared for the sensitivities that emerged in creating the gender wheel, and we struggled to find words and to empathize with each other. As the exhibition opening neared, we were still debating specific word choices and whether to include the wheel in the exhibition.

A colleague argued that our visual gender exhibit with the animal heads was too easy—we were doing the safe thing. By providing the gender wheel, we would be doing the brave thing by allowing all kinds of bodies to be included. The wheel effectively acknowledges that there is a somatic experience to gender, but that alone cannot address the sum total of how gender should be described or assigned.

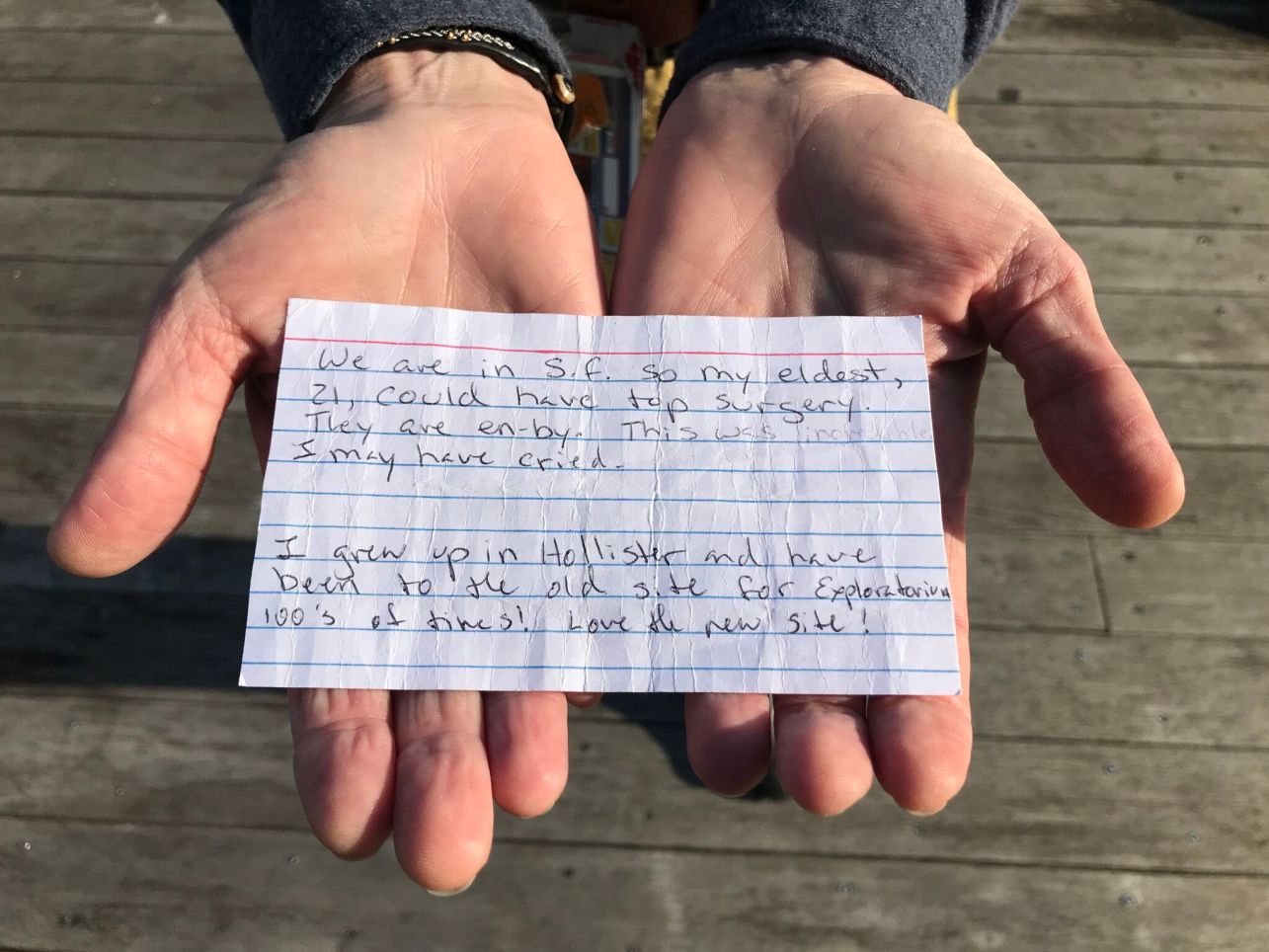

To our delight, most visitors to “Self, Made” greeted our two gender exhibits with enthusiasm. We paired the exhibits so that visitors could quickly and playfully realize how easily they assign gender based on surface cues and then take their time to explore their own layers of gender. Both Gender Blender and the interactive wheel remain in the Exploratorium’s human phenomena gallery where they continue to help families have conversations about gender.

Lessons Learned

Gender is dynamic and complicated. Our attempts to separate it from sex and create a more expansive view ultimately required us to confront our own gender perceptions. While many of us take gender perceptions for granted, others must daily weigh the value of comfort against the expectation of conforming.

Seeing the value in every personal experience, and making progress to create exhibits that represent these experiences, requires compassion, empathy, and patience. But when we have honest conversations and examine our own personal biases, we can make something that helps others (including ourselves and our colleagues) feel “seen.”

As the museum evaluates the exhibition’s impact on both visitors and its internal culture, museum staff have continued to engage with one another on the topic of gender. Creating “Self, Made” was an experience full of discomforts, but our ultimate reward was not just our visitors’ engagement, but our own opportunity to grow personally and culturally.

Our advice to any other museum looking to tackle a complicated topic like gender? Expect it to be hard and to make mistakes, but take the risks. Be open to accepting the limitations of your own experience. Listen to others and keep the conversation going.

Resources

Who Are You? The Kid’s Guide to Gender Identity kidsguidetogender.com

The Genderbread Person www.genderbread.org

Bathroom Boundaries

By Sal Alper and Sam Sharkland

How can we experiment with the phenomenon of socialized gender in a museum setting? At the Exploratorium, we looked to our restroom signs.

As we developed the “Self, Made” exhibition, museum colleagues conducted an experiment on some of the staff bathrooms by changing the signage from symbols representing “men” and “women” to signs that read “brown eyes” and “blue eyes,” along with instructions for “other colored eye people” to go in an all-eyed bathroom in another part of the offices. For many of us, it was the first time we’d ever had to ask if we belonged in the bathroom of choice.

This intervention led to Bathroom Boundaries, a series of mediated inquiry experiences for visitor bathrooms during museum adult hours. In the experience, a visitor heading to the bathroom looks for familiar bathroom signs but is faced with unexpected, seemingly arbitrary categories. This moment quickly leads to confusion or discomfort.

By problematizing the basic necessity of toilet use, we challenged groups who previously may not have considered binary separation as an issue. We encouraged visitors to ask themselves who has the right to access and relief through an empathetic experience.

Here’s how we developed Bathroom Boundaries.

We found allies. Tackling a topic that challenges deeply embedded norms in a personal area requires understanding and support. Our process started in casual conversation but led to staff experiments and a museum-wide discussion. This allowed for buy-in from decision-makers, which in turn supported the programmatic engagement for the public.

We prototyped. Experimenting with Bathroom Boundaries in staff areas gave us direct and honest feedback from our colleagues. We shifted variables to test reactions and feelings of comfort.

We engaged our audience. We used existing labeling practices to mark the site of the experiment and offer guidance for the experience. A writing board and visible staff to take feedback or contextualize the discussions allowed visitors to process the experience, which also provided anecdotal data for us.

Read more about the experiment at https://www.exploratorium.edu/sites/default/files/pdfs/Bathroom_Boundaries.pdf

Melissa Alexander is director of public programs and Dina Herring is a senior new media exhibit developer at the Exploratorium in San Francisco, California. Sal Alper is manager of the Field Trip Explainer Program and Sam Sharkland is public program developer in the Cinema Arts Program at the Exploratorium in San Francisco, California.