This article originally appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

In January 2020, it came to light that the National Archives had altered a photograph that introduced the exhibition “Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote” celebrating the centenary of women’s suffrage in the US. The work, by Getty Images photographer Mario Tama, captured demonstrators at the January 21, 2017, Women’s March on Washington, DC, which became a rallying cry for those concerned about the threat to women’s rights represented by President Donald Trump, inaugurated the day before.

The modified image obscured several of the protesters’ signs, including some with Trump’s name and others with terms representing women’s genitalia. This altered photo had been shown at the archives for some eight months—since the exhibition opened. On the cusp of the 2020 Women’s March on Washington, a Washington Post article called out the revision, and a National Archives spokesperson initially justified the institution’s actions as an attempt to remain apolitical and family-friendly. She also argued that it was defensible to alter the photo because the work was promotional material rather than part of the exhibition.

But within a day of the Post’s report, facing a barrage of criticism from practitioners, scholars, and the wider public, Archivist of the United States David S. Ferriero issued a public apology and, soon afterwards, the altered image was replaced with the original photograph. In his apology, Ferriero acknowledged the National Archives’s responsibility to truth and to the stories of women. He also framed the incident as a crisis of credibility that could only be repaired by greater transparency and scrutiny of internal policies and practices, none of which, however, he identified.

He was careful to stress that the photograph was not censored by an outside party; “the decision was made without any external direction whatsoever,” he declared. Yet, Ferriero did not admit that the alteration was an act of institutional self-censorship.

Defining Self-Censorship

In contrast to censorship, in which a party outside an organization exerts authority to suppress ideas, including artistic expression, self-censorship is exercised internally. In museums and archives, self-censorship can best be understood as the suppression of ideas, including artistic expression, by an individual practitioner—an artist, a curator, or an educator—or by the institution itself in the development and presentation of content.

Self-censorship is often challenging to recognize because the boundaries between it and the routine processes of responsible editing are often blurred. Self-censorship can be distinguished, however, by the impetus that motivates it—fear.

Acts of self-censorship can usually be traced to fears about possible retribution from the state or private funders, or potential lost visitorship. The growing impetus to become a safe space for exploring difficult issues, given the complex dynamics of diversity politics, has created a museum environment increasingly characterized by the fear of offense. Such fears are bolstered by risk aversion—the drive to lower uncertainty—even when risk assumption will more likely lead to successful outcomes.

Though some amount of risk-averse thinking is fundamental to responsible practice, it becomes detrimental when it clouds decision-making. In the case of the National Archives’s self-censorship of Tama’s photograph, the alteration was undoubtedly motivated by fears of repercussions from the Trump administration, the political right, and conservative audiences. Its risk-averse course of action created huge reputational damage when a more confident stance was essential to achieving the exhibition’s goal of recognizing women’s empowerment.

In the fervor to avoid offense, institutional self-censorship often functions as a kind of “othering” that reinforces the marginalized status of disenfranchised groups. Such was the case in the altered Tama photograph; obscuring signs critical of President Trump and those that proclaimed the rights women have over their own bodies was a disempowering act. Celebratory frameworks championing diversity and inclusion in the name of social cohesion, such as the “Rightfully Hers” exhibition, too often exculpate contentious issues and analysis that might have been deployed to transformative effect.

The Ubiquity of Self-Censorship

The fact that Ferriero did not say that the institution had engaged in self-censorship in his apology is not surprising, given that the phenomenon is widely denied and misunderstood. In Western democracies, publicly exercising institutional self-censorship is frequently viewed as a violation of principle. Denial of institutional self-censorship also stems, in part, from the myth that museums are neutral spaces. Sharon Heal, UK Museums Association director, explains this phenomenon:

The very low level of awareness of self-censorship is partly rooted in the complete misconception that museums are neutral spaces. In this misconception, there is no curatorial voice, no authorship, just a neutral narrative—and thus no censorship. I think that message really persists. If you don’t tackle the idea that museums are not neutral spaces, you can’t then talk about what you do and don’t display, what stories you tell, and which voices you exclude.

Acknowledging the illusory nature of neutrality is particularly challenging terrain for federal institutions such as the National Archives. In his apology, Ferriero insists that the archives must maintain “a commitment to impartiality” despite the fact that this commitment and its underlying assumptions undercut the equality agenda of the exhibition.

While it may be comforting to maintain the illusion that self-censorship occurs “over there” and “not here,” it occurs in all kinds of museums in all parts of the world, not just in countries ruled by authoritarian regimes. For instance, at the UK Museums Association’s 2016 annual conference, a poll of 63 delegates attending a session on institutional self-censorship revealed that 51 percent had consciously withheld information from audiences due to its controversial nature. Moreover, the limitlessness of self-censorship makes it more dangerous than censorship, which, in its dependence on external apparatus, is necessarily limited.

Today, unlike during the US “culture wars” of the late 1980s and early 1990s, pressures to self-censor come not only from politically conservative camps but, equally, from the left. Even the most progressive institutions find that a certain level of self-censorship is endemic to their work. For example, museum staff writing interpretive texts need to follow the protocols of institutional terminology documents.

And while social media has introduced empowering platforms that allow audiences to shape museum discourse and action, when weaponized with a mob mentality, these platforms can readily induce museums to attempt damage control by self-censoring exhibitions and programs. Such was the case when the Guggenheim Museum in New York pulled two videos and one installation piece featuring animals from its 2017 exhibition “Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World.”

An online petition signed by more than 700,000 people gave the false impression that the most transgressive of the video pieces, Peng Yu and Sun Yuan’s 2003 Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other, was being performed live at the museum. Nonetheless, the Guggenheim self-censored the pieces, citing threats of violence. Museum leadership did this despite the fact that the curators had conceived the installation piece, Huang Yong Ping’s 1993 Theater of the World, to be a linchpin of the project, as reflected in the exhibition’s title.

Only after the self-censorship occurred did the curators acknowledge the culture clash between contemporary Chinese artists working in the aftermath of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre and animal rights activists speaking from a privileged position today.

The Ethics of Self-Censorship

Self-censorship does not, however, implicitly and inevitably represent an ethical wrong. In fact, self-censorship is sometimes an ethical good.

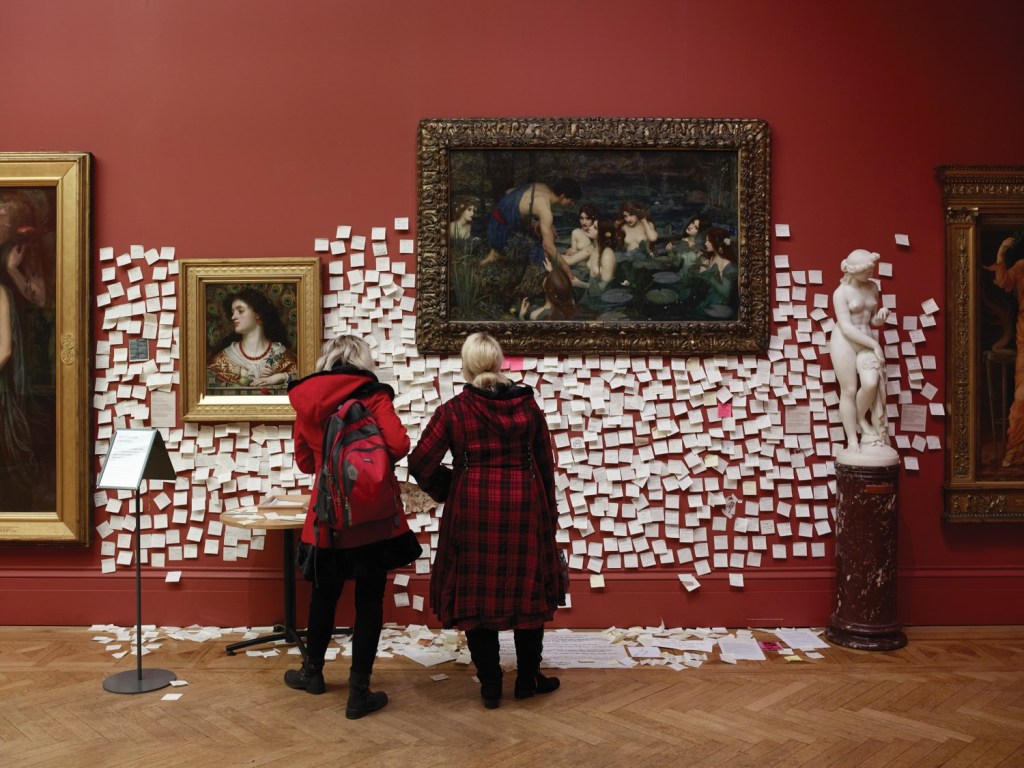

Sometimes it is performed as a means of unsettling sexist, racist, or classist assumptions and practice. For example, in 2018, the Manchester Art Gallery in England removed John William Waterhouse’s 1896 Hylas and the Nymphs from the gallery walls for one week as part of a project by artist Sonia Boyce. The artist was interrogating the display and interpretation of historical works that are increasingly seen to objectify their subjects. This act provoked constructive discourse, as evidenced by the comments on sticky notes Boyce invited visitors to leave in the space where the painting had hung.

Of course, in authoritarian states, where censorship is ubiquitous, self-censorship is a necessary part of everyday work. Practitioners must remove potential triggers in order to protect artists, staff, and the museum itself from potentially grave repercussions.

But because self-censorship is often enacted in the name of protection, it is vital to consider who is being protected and for what reasons. Museum professionals must decide if and how to resist the pressures to self-censor by weighing the ethical costs. This is fundamental to museum work today.

In fact, museum practitioners do have agency when confronted with the pressures to self-censor. The binary construction of censor as perpetrator and censored as victim that has dominated censorship discourse in the arts is no longer productive. The goal is not always to eradicate self-censorship but to accept that developing and presenting museum content is often a delicate dance between resisting and exercising self-censorship.

In some parts of the world, practitioners do not have the freedom to speak openly about their experiences of self-censorship. But where we do, we owe it to ourselves and others to be transparent about these issues, or the phenomenon will remain needlessly opaque. Only with robust self-reflective dialogue can museums make ethically informed, deliberative decisions when faced with self-censorship.

Photograph by Michael Pollard

Self-Censorship: Questions to Consider

- Who am I concerned this project might provoke and why?

- What might the reprisal be?

- How realistic are these fears?

- What risk does the potential self-censorship itself entail?

- What are the real ethical costs of resisting versus enacting self-censorship?

- Have I put proactive strategies and tactics in place (as identified in the Resources on p. 20) to fully appreciate and confidently navigate the potentially contentious nature of the project?

- Have I collaborated both within my organization and with partner organizations for knowledge exchange, mutual support, and joint advocacy?

- How should I weigh my pursuit of professional integrity with my respect for diverse cultural contexts, which might be at odds with my vision?

Resources

Julia Farrington, “Taking the Offensive: Defending Artistic Freedom of Expression in the UK,” Index on Censorship, May 2013 indexoncensorship.org/takingtheoffensive

Janet Marstine and Svetlana Mintcheva (eds.), Curating Under Pressure: International Perspectives on Negotiating Conflict and Upholding Integrity (in press), summer 2020

Farida Shaheed, “Report of the Special Rapporteur in the Field of Cultural Rights: The Right to Freedom of Expression and Creativity,” Human Rights Council 23rd Session, United Nations General Assembly, March 2013 digitallibrary.un.org/record/755488?ln=en#record-files-collapse-header

National Coalition Against Censorship, Guidelines for State Arts Agencies, Museums, University Galleries and Performance Spaces, 2019 ncac.org/resource/guidelines-for-state-arts-agencies-museums-university-galleries-and-performance-spaces/

What Next?, Meeting Ethical and Reputational Challenges: Guidance whatnextculture.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Meeting-Ethical-and-Reputational-Challenges-Guidance.pdf

Janet Marstine recently retired as associate professor from the School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester. She is now an independent researcher and consultant in the US focusing on museum ethics, including self-censorship.