What Chinese museums did during their month-long closure

Almost all Chinese museums closed immediately on January 24, only one day after the city of Wuhan locked down, to reduce the risk of infection in crowded places. Beginning in early February, China’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism launched online public culture and tourism services, which aimed to enrich the cultural life of the public while they were locked in their homes. Viewers could browse thirty virtual exhibition halls of the National Museum of China, search for information about historical relics at the Palace Museum, and attend open courses from the National Library of China. Many of the country’s provincial museums—including those in Zhejiang, Hebei, Jiangxi, and Jilin—developed a platform to gather their resources (virtual exhibitions, online storage, online shopping, etc.) together on one website. According to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, museums across China have moved more than two thousand exhibitions online, attracting over five billion visits during the Spring Festival (January 25-January 31).

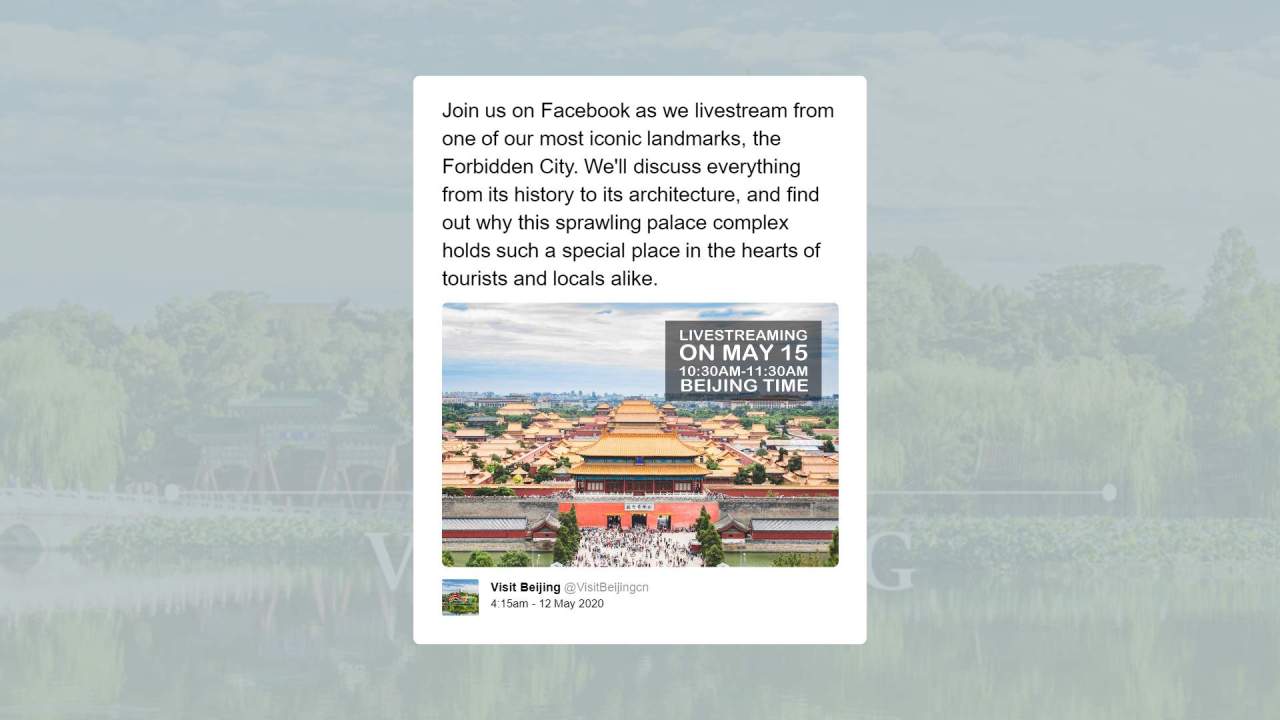

Chinese museums also collaborated with some influential online platforms for livestream events. On April 5, China’s Palace Museum, also known as the Forbidden City, went live online for a two-day streaming extravaganza. Through popular apps including People’s Daily (the largest newspaper group in China), Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), and Tencent News, museum staff took viewers on tours of the ancient imperial mansions, cultural relics, and springtime flora and fauna in the compound. This event attracted over one hundred million views, an astronomical number even for a country with one-fifth of the world’s population.

Some online live programs focused not on Chinese museums, but on other museums around the world. On February 15, the British Museum went live online for the first time on the Kuaishou app (another TikTok-like platform). A Chinese docent at the British Museum led a guided tour of Egyptian culture, Renaissance art, and the East Asian collection at the museum. Unlike on traditional television programs, the docent could interact with the audience, and got immediate and direct responses via “bullet-screen comments.” This ninety-minute event attracted two million views and five hundred thousand likes.

How Chinese museums reopened

On March 17, more than 180 museums in China reopened after month-long closures, according to a release published on that day by the National Cultural Heritage Administration. Only museums, memorials, and cultural heritage sites in low-risk outbreak regions were allowed to gradually resume operations, with the prior permission of local authorities. In medium-risk regions, open areas of cultural heritage sites and ruins-based museums could resume opening to the public in an orderly manner, while their indoor areas had to remain closed. Museums in the high-risk outbreak regions could not open at all. In the middle of April, several museums in Beijing, Guangzhou, Dalian, and Xiamen that had reopened were required to close again due to the rising number of COVID-19 confirmed cases in these areas.

Continuing precautions to control the pandemic, museums asked visitors to make online appointments and pledged to limit the total number of visitors, stagger visiting periods, and offer digital tour services to avoid public gatherings. The Shanghai Museum, for instance, releases two thousand online appointments every day, only 30 percent of its capacity. Although the appointments on its first reopening day were booked quickly, only 996 of the two thousand registered visitors went to the museum.

The new arrangements mean that visiting a museum is not an easy thing. Visitors must remember to bring their ID and show their green health QR code, to prove that they haven’t been to high-risk regions or had close contact with sick individuals. They are required to wear face masks and the museum should check that their body temperature is below 99.1 degrees Fahrenheit. They must stagger their visiting periods and keep six feet from others. All the cafes and restaurants are closed, and only vending machines provide beverage and snacks.

Reopening museums during the pandemic also means new strategies for exhibitions and programs. Because of travel restrictions, many temporary exhibitions and other academic and educational programs had to be postponed or even canceled. Many museums had to extend the temporary exhibitions opened before closure, and curated special exhibitions with their own collections. Some museums also tried to find cooperative opportunities with museums in other East Asian countries, both because of geographical convenience and better control of the pandemic in these counties compared to others around the world. All group visitors and onsite educational programs are still postponed, leaving a gap in engagement for students.

The financial implications of COVID-19 also concern Chinese museum practitioners. A February 2020 survey of 514 practitioners in visual art organizations (including museums, galleries, auction houses, art media, and art funding) showed pessimism for the near future of this field. 42.4 percent of respondents thought COVID-19 would have a strong negative effect on the art industry, a quarter estimated that they and their organizations’ income would decrease by more than 50 percent, and only 5.6 percent thought their income would remain the same in the first half of 2020.

Although many public museums in China are free and rely on national and provincial special funds, the cancellation of activities that charge a fee still affects their income. For private museums, the situation is worse. They lost their income from tickets and events during the month-long closure, and some of them had to change their plans for temporary exhibitions this year and even next year. In the survey, respondents wanted the government to provide tax concessions (70 percent) and rent and utility subsidy (67.6 percent). During this hard time, some provincial governments offered financial help to museums. For example, on March 27, the Henan province in central China announced a plan to offer loans of no less than one billion yuan ($141 million) to help revive the cultural and tourism sectors that have been hammered by the novel coronavirus outbreak. Museums which “have a relatively mature market and the potential for cultural product innovations” would be supported by this fund.

What can we learn from COVID-19?

During this time, it is important for museums to think not only about how to survive, but how best to serve the public.

Almost all middle-scale and large-scale Chinese museums have continued to put virtual exhibitions online, since many people are still restricted from traveling outside or are afraid of going to public spaces like museums. However, these exhibitions have been criticized for their homogeneity and lack of creativity, including by Jian Liu, Deputy Director of the Shanghai Museum Data Center. Museums should think about the unique characteristics of the digital space and treat the online exhibition as an independent project instead of an appendage of onsite exhibitions. Even with the same objects and themes, the ways of curation and storytelling are different. The COVID-19 pandemic is an opportunity to think about the meaning of digitization and what makes a lively online experience, with content that goes beyond pictures and videos of objects.

There are also shortfalls to livestreaming. Although the live online viewing of the British Museum on June 30 gained great attention and had many visitors, many watched it for just a few minutes and then left the page; the average viewing time was only 2.3 minutes, as estimated by Udazrenz (see this translated screenshot for a data breakdown). On the Zhihu app (a Quora-like platform in China), viewers commented that they were attracted by the big name of the Palace Museum, and the unique opportunity to enjoy the palaces with nobody there, but left disappointed by its poor recording effect, slow pace, and lack of interaction. On the other hand, sometimes too much interaction with the audience is not a good thing either. The docent of the British Museum, for instance, had to deal with live comments like, “How much are these artifacts, can we buy them?” and “the British Museum should return these Chinese national treasures to China.” Museums must consider not only technical issues but, just as important, how to interact with the audience in a new way in the virtual world.

About the author:

Yiru Zhang is a graduate student in public humanities at Brown University, originally from Shanghai. She is interested in public art and museum education. She has had museum education experience both at the Shanghai Museum and Harvard Chinese Art Media Lab.