A doctor friend recently shared a social media post listing a five-point coronavirus plan:

- Masks

- Close bars

- Socially distance

- Test & isolate

- Outside > inside

Like her, it was matter-of-fact, succinct, and assured. But the “Outside > Inside” bullet made me think about a much mushier question: What are museums to do in these times of virus and protest? Outside is a very important place these days. It’s where the virus disperses and the demands for justice coalesce. Our sidewalks are critical spaces now, and I think our museums should be spending more time on them.

I’m not alone in thinking this. Organizations like Micro and The Floating Museum are helping push forward the concept that museums should work outside their walls more, particularly in communities of color where museums are rarely located.

To help museums that are considering this approach, I wanted to share my experience developing immersive outdoor exhibitions, hitting upon some of the tenets of good storytelling I’ve discovered in the process.

Public Space > Great Halls

For the past fifteen years, sidewalks, alleyways, parks, and publicly accessible buildings have been the stages on which I produce walkable stories. My projects (under the Walking Cinema title) combine smartphone audio, augmented reality (AR), and GPS with installations (both official and whimsical) to create hour-long immersive walks. In the museum context, audio guides are interpretive aids, but in a Walking Cinema project the audio and the world around you become the exhibits themselves. We enhance the experience with small installations and artifacts audiences discover as in a scavenger hunt, but the overall goal is to lock these objects into a compelling narrative—a page-turner, if you will—driven by their footsteps. I see these tours as a critical extension of the gallery experience, especially as museums make efforts to reach out to their surrounding communities.

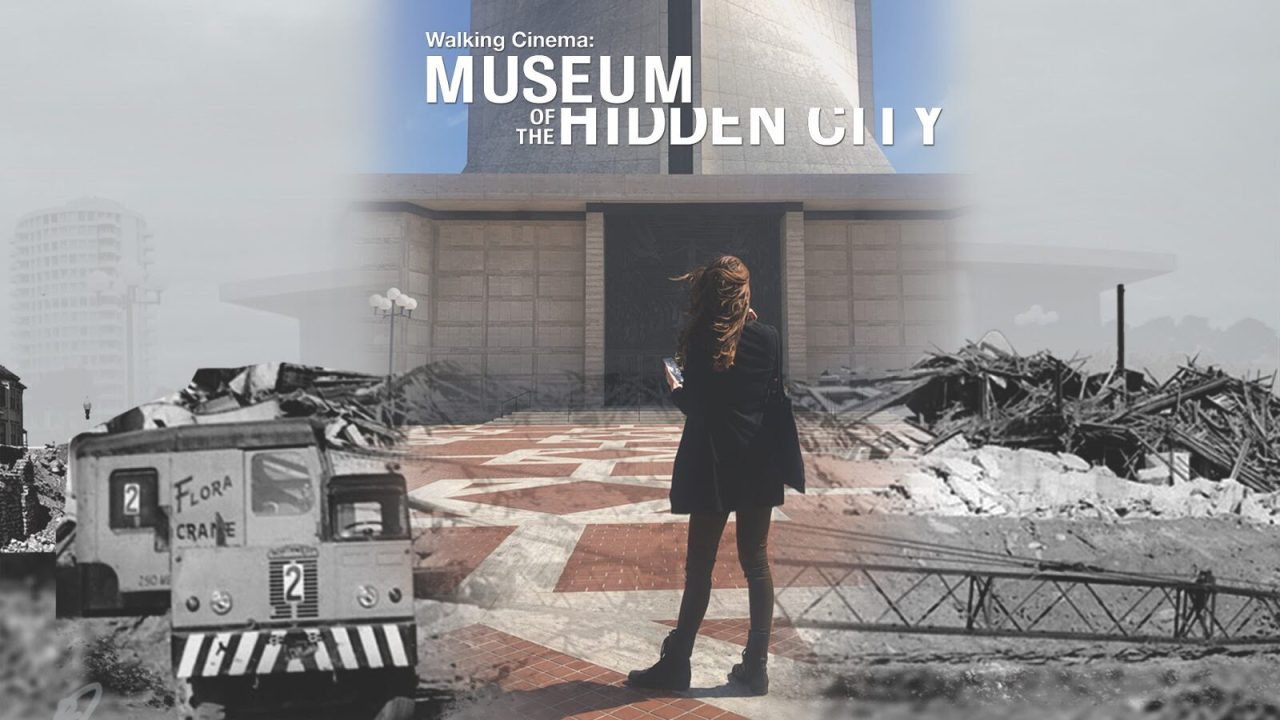

Two years ago, Walking Cinema embarked on a project to create a multi-site, multi-episode exploration of San Francisco’s affordable housing history called “Museum of the Hidden City.” The goal was to make gentrification and other intersectional issues of race, urban design, and housing easier to visualize and understand for a range of audiences. After getting a couple local and national grants to build the first episode of the project, we began a production process that I think is instructive for museums these days, both in a BLM and a COVID sense. By telling the story of how we built “Hidden City,” I hope museums will begin to consider this format as a means to run exhibits during a pandemic and start critical conversations about race, equity, and voice.

Blind Spots > Monuments

“Museum of the Hidden City” was awarded the 2020 Gold MUSE Award for mobile apps, with the judges being particularly struck by how “the echoes of the past [are] brought to life with a compelling and interesting narrative.” To produce that “compelling and interesting narrative,” I use a process called “scripting with the landscape.” It’s a combination of historical research and on-site landscape studies that results in audiowalks that feel cinematic, like a movie you can walk into.

A key initial step in this process is to find “tent poles.” These are sites, artifacts, views, or secret spots that audiences will want to tell their friends about after the experience. They often serve as symbols for the overall story being told. While typical historical walking tours look for the monumental, postcard-friendly sites in a neighborhood, strong narrative experiences often involve revealing small details in the landscape that crack open huge questions looming in a neighborhood’s, a city’s, a nation’s psyche.

Many such details in the housing saga can be found in the Fillmore neighborhood of San Francisco. We decided to set the first episode of “Museum of the Hidden City” there, because it’s where a large-scale utopian vision of civic architecture came head-to-head with a vibrant but economically declining Black neighborhood in the 1960s. Under the banner of creating more opportunities and better lives for its inhabitants, the city’s Redevelopment Authority flattened eighty blocks of mostly Victorian housing and effectively destroyed the “Harlem of the West.”

What appeared to be a slum to outsiders had highly functional components for its African American inhabitants, details that the project’s designers just couldn’t see. These kinds of design blind spots are still extant in the existing streetscape: communal gathering spaces which now sit empty, purely residential blocks devoid of the once-ubiquitous corner stores, hastily built security fences, plaques for a lost jazz culture, and single Victorians engulfed in block-style housing. As I was discovering these “tent poles,” I started developing a story around them by finding compelling characters to tell it.

Fewer Characters ∝ Stronger Story

Initially, I thought I would focus the narrative on M. Justin Herman, the kingpin of redevelopment in San Francisco in the 1960s (often compared to Robert Moses of NYC). I was fascinated by his layers of civic duty, covert racism, aesthetic fascination, and bulldog force to build, build, build. But through active feedback from our advisors on the project (from the fields of African American studies, geography, history, and architecture) I was dissuaded from using the lens of a white man to tell the story of the destruction of a Black neighborhood. Still, I knew that the story would be stronger with characters who were torn between Justin’s vision and drive to change the neighborhood and an understanding of the richness of the Black community that lived there.

With that in mind, I worked with two talented journalists to conduct weeks of on-site and archival, character-driven research. After interviews and walks with over twenty individuals, we decided to zoom in on two who were living and working in the neighborhood at the time of redevelopment: an architect trying to innovate his craft through community input, and a preacher’s daughter questioning her father’s leadership of the redevelopment efforts. We conducted hours of interviews with them, and what emerged were stunning parallels in how they both welcomed the renewal process but came to doubt its positive impact as it progressed. They each had to confront doubts about those they admired: the girl confronted her father and the architect confronted Justin Herman. This kind of emotional arc and zoom-in on singular characters can be counterintuitive for some historians and curators who have an urge to be encyclopedic in their collecting. But when stepping outside the museum, such streamlining works to your advantage, especially if audiences are also navigating the use of a new media platform.

With our characters’ stories in mind, we revisited our tent poles, which brought new meaning to existing ones and helped others emerge. One of the most important tent poles to emerge in this process were two lost church murals, related to the preacher’s daughter’s story. Her story pivots around the point when her father is forced to destroy his own church as part of the redevelopment plan. Whereas he could have tried to have the building moved or saved, he wanted to show the community he too was willing to sacrifice to build this new city. He told us in an interview that he did manage to save two of the massive murals that adorned the walls of the church, but he didn’t know where they were. We searched and searched, and some people said they were gone, or they were in storage outside the city. But then we discovered that they indeed were still around the neighborhood, pegged to the walls of a nondescript office building lobby. These murals, when combined with an AR overlay of the destruction of the church, turned into a perfect tent pole, cementing the girl’s growing doubt of her father and the entire redevelopment process.

Poetry + Prose

But even after finding these voices and sites, we still had to find a way to speak to younger audiences. One of our main targets was high school and college students, and while our interviews were informative, they lacked the pace and intensity younger audiences tend to respond to. Through a partnership with Youth Speaks, a non-profit that teaches literacy through spoken word poetry, we found two young African American poets to give a voice to the architect and the preacher’s daughter. I then worked painstakingly with the poets to write a script that stuck to the facts from the interviews but also included their own perspectives. In the end, we co-developed a sound that was both factual and poetic.

To hone the young poets’ writing, we did some exercises. We went to various tent-pole sites, where the poets free-wrote to capture their emotional reactions. We played cuts of the interviews for the poets so that they could understand their character’s perspectives on specific events and places. And as they wrote their poems, I wrote narration for them to put the poems in context and properly guide audiences through the walk. The effect is a flowing, lyrical narrative that is lovely to walk with and draws in younger audiences. One young beta tester who lives in the Fillmore commented, “I found myself mourning for a place that ceased to exist long before I was born, all the while, in my ear, the question is asked ‘Should these have been saved at all, devoid of the place for which they were intended?’ I’ve walked by these artifacts probably hundreds of times and never knew they were there.”

Backyard > Lecture Hall

As the Museum of the Hidden City rolls out this year and develops more episodes, we plan to look deeper at how we can connect audiences with the communities being highlighted. Based on user testing, we struck upon the idea of monthly group walks that end in an outdoor space where a “docent” from the community fields questions about the issues raised in the walk. Other concepts are to link a more formal institution like the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts to the Museum of the Hidden City, thus giving the center, in a sense, an auxiliary gallery during COVID. We are also looking into ways to help spark audience action after they have gone on the tour. Although I don’t think of this project as political, I believe it is a mechanism to open audiences’ eyes to how racially biased policy is inscribed in San Francisco’s and many cities’ urban fabric. And by tuning your eye, you can see opportunities to further housing justice in your own neighborhood. Such connections to the real world, to current issues, to our cities and civic duties, can only be enhanced as museums embrace the displacement of the gallery to the streets. And as they begin to work from a premise that outside is indeed greater than inside.

Project Website: www.seehidden.city. Download the app here (Android and iPhone).

Running: now-at least end of 2020. On-site experience is much better, though it can be listened to remotely.

About the author:

Michael Epstein is a screenwriter, transmedia director, and expert in place-based storytelling. He has an M.S. degree in Comparative Media Studies from M.I.T., where he specialized in developing multiplatform documentary films. In 2006, Michael founded Walking Cinema, which has developed cross-platform apps for MTV, PBS, the Venice Biennale, Audible, and many museum and broadcast clients. He has taught at the California College of Art, the University of Missouri, and the Berkeley School of Journalism Advanced Media Institute.