This article originally appeared in the November/December 2021 issue of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

Deepest gratitude to the Getty Foundation, which has supported for over a decade the AAM-Getty International Program at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo to forge connections between museum professionals in the US and globally in a shared understanding of museum missions, practices, ideals, and aspirations.

The Path to Colonial Reckoning

The Path to Colonial Reckoning

By Wesam Mohamed

On July 26, 2021, the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities announced the repatriation of a Nikaw-Ptah statue from the Netherlands. The statue was first unearthed in Egypt by local looters as part of illicit digging organized by people looking to get rich on the high demand for Egyptian antiquities.

Illicit digging is a real problem for archaeologists because they cannot identify who was digging, where they were digging, when the object was discovered, or how it was moved out of Egypt. Therefore, most of the object’s background is lost forever. The story of the repatriation process most likely replaces the original history of the object since it has lost its original context.

This story is all too common in many parts of the post-colonial world. In Egypt, tales of illegal digging, artifact trafficking, looting and looters, and repatriation of antiquities are frequent, especially in crisis situations such as war or political upheaval. The Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities and the Tourism and Antiquities Police need the international community to stop these assaults on Egypt’s tangible past.

For centuries, most of the Western world ignored Egyptian heritage altogether. That changed in 1798, following Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign. From that time forward, many Western museums and private collectors established their collections from looted Egyptian antiquities. No one record exists of all Egyptian antiquities in museum collections, much less those privately owned. These colonial practices disconnected Egyptians from their own heritage. Removing these items forever altered their historical and cultural context.

Here is one example of this in my work in Egypt.

In April 2021, 22 mummies of the most important kings and queens of ancient Egypt were moved from Cairo’s classic Egyptian Museum to the newly constructed National Museum of Egyptian Civilization. The mummies’ journey to their new museum home helped reverse more than 150 years of systematic looting of Egyptian heritage in ancient Thebes (now Luxor).

Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities organized “The Pharaohs’ Golden Parade” in the streets of Cairo to celebrate the mummies’ move to their new home. The parade evoked an unprecedented wave of local pride and connection to Egyptian heritage. It brought ancient history into the streets where Egyptians walk and wander daily and inspired large numbers of Egyptians to visit the National Museum to see the new display for the royal mummies.

What can we all learn from this example? First, we should be tireless in our efforts to reverse the impacts of cultural colonialism. Organizational and individual acts are necessary to help Egyptians reconnect with their history and to end the cultural colonization of Egyptian heritage.

Second, decolonization is one of many tools museums have to enhance cultural life and connect people to their own heritage. One of the first steps is accessibility to collections. Egyptians inside Egypt have the right to connect with Egyptian collections in London, learn from Egyptian collections in Turin, and enjoy Egyptian collections in Paris. We must make this a priority.

Finally, organizations with colonial pasts have an ethical responsibility to the communities to whom those collections belong. These obligations include promoting cultural awareness, building relationships with heritage, enhancing identities, and provoking ownership.

At its heart, decolonization is as much about doing the right thing as it is about allowing for cultures to regain a sense of ownership of their past. It must become a priority for museum professionals worldwide.

Wesam Mohamed is curator at the Ministry of Antiquities in Egypt.

Homeland Museum of Knjaževac

Museums for All

Museums for All

By Milena Milošević Micić

Though museums should never be neutral, they must be as objective as possible as they serve their roles as truth- and science-based emitters of knowledge and forums for public debate. Museums should be communication channels and places of change and dialogue, initiators of the peace-building processes among, for, and with their communities.

Museums also play a significant role in teaching the importance of cultural heritage to the past, and to the present. They not only help us understand who we are as individuals and what is, or should be, our role as humans in the world, they are also initiators of, and mediums for, cultural communication.

I have seen all of these principles (and more) in action as part of the Balkan Museum Network (BMN) (bmuseums.net/about-us). The group exists to celebrate, preserve, and share the complex common heritage of the Balkans and to create a strong, collective voice for Balkan heritage and the museum profession. BMN promotes museums as institutions of learning, discovery, and inspiration. We believe museums are active agents of social change—owned and guarded by society, open to everybody, and for the benefit of all. We approach this work with a spirit of cooperation and commitment to overcome provincial politics as we encourage museums throughout the Balkans to be resources for education, communication, peace building, and conflict resolution. In September 2021 BMN hosted the Meet, See, Do international conference where we reassessed our roles and relevancy in a post-COVID world in the areas of common heritage in danger, risk management, collection management, audience development, and access and inclusion.

As a member of the network’s Balkan Museum Access Group (BMAG), a group of museum professionals from the region who have been trained by UK experts in the areas of access and inclusion, I have focused on another imperative: accessibility. This peer-learning group of nine individuals from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Greece, North Macedonia, and Serbia are putting accessibility into their daily museum practices. We have managed to identify, overcome, or even remove some of the barriers that exist in our institutions and societies, exchange knowledge and experience, re-establish connections, and change attitudes. These bridges will open new perspectives and possibilities in the region that will improve not only the quality of work in our museums, but also the quality of life of people in our communities. They will help us grow and develop both professionally and personally in our shared journey toward fulfilment of our mission as dedicated museum professionals and activists.

Throughout my museum and cultural heritage career, I have seen the significant role museums play in the sustainable development of the local community. My everyday museum practice; active participation in professional associations and international exchanges; and engagements with BMN, BMAG, and the AAM-Getty International Program have all helped me better understand how museums open new spheres of possibilities. Museums can help people express their right to freely participate in the cultural life of their community, allowing them to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

Milena Milošević Micić is museum advisor and art historian at the Homeland Museum of Knjaževac in Serbia.

Humanizing the Museum Field

Humanizing the Museum Field

By Germán Paley

“Accessibility is much more than guaranteeing the access to what already exists but actually it consists in bringing into existence the world you DESIRE.”

Museum practice is both social and collective, moved by affection for and professional inspiration from colleagues around the globe. Museum professionals worldwide share a common belief that the social dimension of our institutions helps us expand our horizons.

We are truly nodes in a network that gives us significance, and we can strengthen our field if we focus on people. Collections serve as a departure point for meaningful connections, providing a web of resilience based on respect, empathy, and a common ground of shared knowledge to surmount the collective traumas of homophobia, classism, racism, ageism, and credentialism, among others.

I like to think of a museum as energy. What is the energy of your museum right now? What do you perpetuate? What do you change? How can you transform your space, objects, and experiences into more meaningful experiences for others?

Between the Inherited Past and Uncertain Future

2020 was a watershed, a year when museum practice changed forever. The COVID-19 pandemic forced museum professionals globally to reflect more deeply on our responsibilities to not only our visitors but our communities.

Moving forward, we must continue to reimagine new bonds and connections to take our institutions to a place where they are meaningful for the people that animate them (visitors, staff, communities, etc.). We must be innovative in the ways we fulfill our mission; we must reimagine museums with a humane core, activating new narratives (and poetics) based on a museology of affection. This ideal deconstructs the very notion of museum and urges reconsideration of all of our inherited ideas about museum practices. In doing so, we open up new experiences where the “visitor” becomes the real focus of the museum, perhaps, becoming a “local.” 😉

The Museum as an Exercise of Community

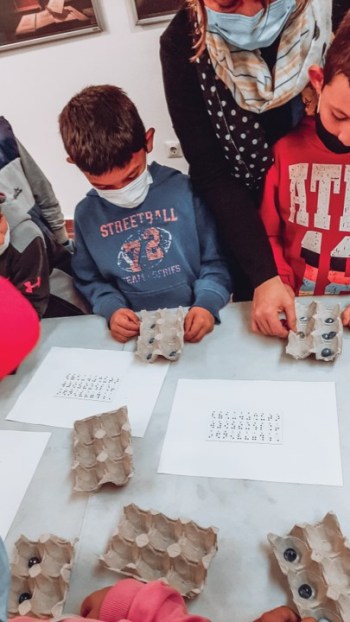

Here is one example from the “before times.” In 2016, I began to develop the Community Outreach Program at the Museum of Modern Art of Buenos Aires. Our goal was to transform the museum into a participatory experience in which we encouraged visitors to relate our collections to their own life and experiences.

Our core purpose was El Museo Humano (“Humanizing the Museum”). We used art as a medium to address issues such as inequality, solitude, and exclusion along three interconnected lines of thought and practice: senior citizens, mental health and accessibility, and citizenship participation.

As educators we listened to people and built bonds of learning together with them. Seniors taught the museum about resilience and hope, children on the autism spectrum taught us different ways to discover a painting, and people who are blind allowed us to see through perception.

New Questions Are Required

As the world continues to grapple with this global pandemic, I’m struck by how these experiences are a powerful reminder of the many ways museums serve our communities, creating a space for dialogue and belonging. Museums must seize this moment to continue to be more people-centric. Colleagues such as Tatiana Quevedo at Bogota, Colombia’s Contemporary Art Museum or Encarna Lago at Lugo´s Museum Network in Galicia, Spain, have inspired me to address the museum field’s most urgent task: providing alternative avenues of connection when public health protocols require distance and isolation.

As museum practitioners, it is our responsibility to open our institutions (and, more importantly, ourselves) to a genuine dialogue with others to transform what we do, how we do it, and with whom. Museums are alive and made by people. Who gives life to your museum? How is life respected at your museum? Use these questions as the compass in charting new routes.

As we emerge from the pandemic, my hope is that the lessons we learned will firmly debunk the perpetual inside-outside binary our field seems to cling to.

Germán Paley is a social museologist and art educator who collaborates as an external adviser on accessibility at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) in Mexico.

The Twilight Zone

The Twilight Zone

By Ignacio Paravano

When you are an exhibit designer, migrating from a physical space (walls, displays, and showcases) to a virtual reality feels like stepping into the Twilight Zone. The fear of this unknown often makes us too conservative in practice. The results are often tepid, mere reproductions of the traditional museum model presented in the virtual space.

We must resist the urge to follow this path as it misses the opportunity we have to dream up a new kind of virtual museum experience, one that leads to a more all-encompassing, inclusive exhibit design.

When that unknown realm no longer scares us, when we overcome doubts, when we dare to rupture the classic idea of a museum, we can then begin to imagine and create a different, bolder, more daring virtual museography. Ultimately, it is a museum with no space limitations.

Physical museums have boundaries. Exhibition halls have walls that limit us; the museum’s location impacts visitation. These dimensions narrow the possibilities for exhibitions. As those boundaries expand, as we blur lines, crack limits, and capture the power of virtuality, museums become more reachable, more democratic.

My work as an exhibit designer is mainly geared toward memory museums and activism. Through immersive and interactive practice, institutions connect with visitors through resources that mobilize and raise awareness, create open dialogue, and offer spaces for reflection. I have found the internet to be among the best tools for this work.

Embracing virtuality has not only helped me open new spaces and a direct interaction with visitors, but it has also become a platform to reach an audience that would not otherwise visit the museum. In creating the Virtual Memory Museum of Guatemala, I sought to break down those walls through established structures and a new space for activism. Our goal was a museum for all: available everywhere and anywhere.

The original Guatemala Memory Museum served first as a place to gather and debate. It was an educational space of a more inclusive history of Guatemala, including the country’s past history of violence and genocide—the many stories missing from official government accounts.

The museum’s work is vital in a nation where oblivion is state policy. Having to close this space due to the pandemic was a hard blow for the memory, truth, and justice this Central American country has sought for so long. Virtuality was the option to stay “open” and keep memories alive.

So 2020 was the year of our virtual museum. It became a useful resource for educational institutions, for those young people who want to know the unofficial history of Guatemala in a high-impact, far-reaching, inclusive space. What was devised as a counterpart to the physical exhibition became a great outreach tool, a new place to gather and reflect.

The objective of a virtual museum is to be inclusive. It is how we can take our exhibits to homes, schools, and communities in the most remote regions of Guatemala. Just a few months after its launch, the virtual exhibition has had several thousand visits, thus multiplying the usual flow of visitors into the museum.

Virtuality is the key to creating new narrative forms, even some not thought of until now. I don’t believe virtual museums will ever replace the physical museum, but we cannot ignore this new tool. We have the choice, as museum creators, to use these new technologies and ponder the new possibilities they afford, thus democratizing museums and making them more inclusive.

Isn’t that the goal after all?

Ignacio Paravano is an exhibit designer at Casa de la Memoria de Guatemala.

Wherever and Whoever You Are

Wherever and Whoever You Are

By Rebeca Richter

Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC), the National University´s Contemporary Art Museum in Mexico City, is not only a museum. It also perceives itself as a vehicle for social and cultural change; a laboratory of aesthetic, playful, and meaningful experiences that develop critical thinking; and a museum with a democratic and open character that challenges plurality and offers multiple visions of reality.

The COVID-19 global pandemic forced us to embrace a digital perspective in response to the isolation of quarantining. Connecting and participating with others has become more urgent, and thus we have been focused on advancing programs that are more necessary and timely than ever.

Similar to diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI) initiatives in the US, MUAC has its DIA Project, which proposes a series of curatorial, artistic, pedagogical, academic, and communicative strategies that measurably improve our institution’s diversity, inclusion, and accessibility. We also put special emphasis on building communities from an empathic and affective perspective of shared knowledge and co-creation. Here are some of the highlights of our new programs.

We solicited viewpoints and ideas on inclusive and diverse museums, through an open call to museum professionals and museum-goers, to produce a collective manifesto: “Museums for all” to include many voices, images, and sign language. It was intended for the general public and students of the Center of Attention for Students with Disabilities of the Ministry of Education nationwide (muac.unam.mx/evento/manifiesta-tu-museo).

We launched Brillantinas (@brillantinas_muac), a digital mediation space on Instagram that shares artistic practices and methodologies through the lens of gender. Brillantinas also includes free downloads of publications, conversations, music, stickers, and videos, spreading the message beyond the digital realm.

Another initiative is called “Ni bonitas ni calladitas” (neither quiet nor pretty), a Mexican saying that empowers women to be more than a suppressed object of desire. This program for self-care highlights gender issues through workshops, talks, a bazaar, stand-up presentations, and more. It is a venue for the women of a low-income community to share empathic tools to become more supportive of each other and thus stronger in the face of everyday challenges.

MUAC is also digitizing our artistic and documentary collection and, at the same time, organizing an international academic meeting, Heritage in a Bit, to bring together digital preservationists, heritage curators, activists, artists, and cultural critics to reflect upon the contemporary conditions of digital preservation from cultural and museological practices.

And finally, there’s #MUACdondeEstés (#MUACWhereverYouAre), a digital response to the pandemic that includes diverse and engaging content. Our #TBT (throwback Thursday) posts have included audiovisual presentations of past exhibits; video tutorials on how to make several artsy gadgets at home; editorial recommendations from our past exhibition publications (with free PDF downloads at muac.unam.mx/publicaciones); Sala 10, a virtual space showcasing multimedia contemporary art, mostly new releases—some specifically created for this space; and podcasts like Gran Hotel Abismo that discusses art, critical theory, and visual culture from an enigmatic, philosophical, spectral, and very much metaphorical hotel on the edge of a cliff (muac.unam.mx/podcasts/gran-hotel-abismo).

Throughout it all, and throughout this past year, we have found that our greatest strength lies when WE (staff, interns, visitors, our communities) work together with artwork, collections, and accesible physical spaces as well as with knowledge, emotional understanding, and digital equipment. Broadened perspectives are an asset to our team and our continuous advancement toward an active, innovative, and inclusive museum.

It has been difficult, to say the least, to keep up with the digital avalanche, with a closed physical museum space, within a lonely house/office, under Zoom-mania and insomnia, with all the frustrations, fears, and losses that come with this pandemic.

But I’ve realized that this work is not about me; its not personal. So many things that have bothered me or given me this sensation of being lost, less professional, less empowered, less effective are just because I can’t feel the others. In the end, people who work at museums do it for someone else. The result is seeing people at the exhibitions or workshops or seminars enjoying themselves, learning, participating.

Now I can’t actually experience this, but I know they, you, are there reading and watching and listening. And hopefully feeling less lonely and more motivated. So yes, museum work and diversity, inclusion, and accessibility programs are about and for you, and me, but substantially, they are for us.

Rebeca Richter works in Strategic Alliances at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) in Mexico.

Museums and Radical Change

Museums and Radical Change

By Dr. Winani Thebele

Museums around the world are locked in conversations about decolonization, change, equity, diversity, innovation. For most museums this means acknowledging our colonialist histories and doing what we can to mitigate the damage. Nowhere is this truer than at the Botswana National Museum.

Many museums in the Global North and South were founded with colonial tendencies. This explains the existence of outdated public spaces that are racist, elitist, and full of demeaning narratives and stereotyped displays of colonized people and cultures. This also explains the global outcry for museums to decolonize, review their collections, conduct provenance research, and, above all, restitute cultural property back to countries of origin.

Decolonization entails breaking away from all colonial shackles and assuming a new and different posture that stands for all equally. Museums that ignore the harmful effects of colonization will remain irrelevant and isolated. Museums of the international community often stay relevant by addressing a wide range of contemporary issues (in Botswana it is HIV, xenophobia, passion killings, women empowerment, unemployment, refugees, and restitution). We’ve learned already that our museums should open doors to all members and classes in society and also act as a platform for the practice and expression of our visitors’ talents and views.

Central to all of these innovations is the need to reassess our collections, do provenance research, and repatriate items to their countries of origin when applicable.

The Botswana National Museum, in partnership with the University of Sussex (project host), the Brighton Museum, and the Khama III Memorial Museum in Botswana, is involved in one such project with the colonial-era collections of the UK’s Brighton Museum. The project, “Making African Connections: Decolonial Futures for Colonial Collections,” is a two-year research project inspired by calls for the return of African colonial-era collections in UK museums and by actions toward the decolonization of museums.

The partnership is a collaboration between regional museums in Sussex and Kent with African institutions, museum professionals, and historians and African diaspora interest groups. Though our ultimate goal is the repatriation of Botswana’s material culture, our work seeks first to include Africans in the interpretation and future of African collections in UK museums. This includes making the UK museums’ collections digitally accessible to African publics and the diaspora and centering African voices and views in interpretation.

The project demonstrates that decolonization is possible through co-curation of collections, provenance research, and collaboration with colonialist museums. It supports my own research area and thesis, The Migrated Museum: Restitution or a Shared Heritage?, that decolonization and shared heritage are not mutually exclusive; the two concepts are actually inseparable.

“Making African Connections” demonstrates how the role and responsibility of the global museum has evolved from being the custodian of objects to being a civic space and a public asset. It has become a prism of identity and steward of cultural heritage and collections. Our work together shows effective decolonization efforts across international borders. That the involved museums are meeting their expected roles in less traditional ways should inspire museums lagging behind in the call for decolonization, restitution, and community orientation.

Respecting cultural heritage is the very least we should expect from our international colleagues.

Dr. Winani Thebele is chief curator and head of the Ethnology Division at the Botswana National Museum.