This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s January/February 2023 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

“I greatly appreciate learning about cultural objects, ancient history, and global cultures different than my own, but this should not be at the expense of perpetuating the harms inflicted by colonialism.”

—2022 Annual Survey of Museum-Goers, open-ended comment by respondent

Collections lie at the heart of museums, and values regarding the ownership and control of collections are central to museum ethics. As we look toward the future of the sector, it is vital to acknowledge that the field is at a tipping point where these values are radically shifting. In recent decades, an avalanche of legal battles, legislative action, and community outcry has expanded the terms of debate from legal compliance to broader ethical issues, especially regarding items in museum collections linked to war, looting, and colonialism.

Epic shifts in standards and practices are being validated by global, national, and institutional examples. The landmark report The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage in 2018, commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron, prompted museums around the globe to reconsider their positions on the repatriation of material looted from Benin in the 19th century. In 2022 the Canadian Museums Association (CMA) released a report sparked by the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Advocating a proactive approach to the return of cultural property, CMA exhorts museums “Don’t Wait, Repatriate!”

In the US, the Smithsonian Institution is leading the way, revising its policies to allow shared ownership and the return of objects for ethical rather than legal reasons. In October 2022, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art transferred ownership of 29 Benin Bronzes to the National Commission for Museums and Monuments in Nigeria. At the ceremony announcing the return, Lonnie Bunch, Secretary of the Smithsonian, declared, “Not only was returning ownership of these magnificent artifacts to their rightful home the right thing to do, it also demonstrates how we all benefit from cultural institutions making ethical choices.”

Claimants Rights

Societal shifts drive the evolution of law and vice versa. In the past, governments were more likely to focus on protecting owners, including museums, from demands for repatriation. (See, for example, Australia’s 2013 Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan Act). Recent legislation is more likely to strengthen and expand the rights of potential claimants. One example: in 2022 New York state passed a bill that requires museums to identify art stolen from the Jewish community during the Nazi era—essentially codifying what had been until now voluntary guidelines for the museum sector.

This ethical and legal evolution is complicated by rapid changes in technology. Reproduction of objects (whether as digital images or the digitally enabled creation of physical duplicates) creates the potential for what has been dubbed “digital repatriation.” This can allow museums to retain original material and give digital or physical copies to the cultures of origin, or the other way around.

The ethics, logistics, and effectiveness of these approaches are still the subject of debate. The Institute for Digital Archaeology (IDA) has been urging the British Museum to replace the Parthenon Marbles with robotically carved copies, guided by 3-D scans, and return the originals to Greece. The accessibility of digital technologies is even eroding museums’ ability to control the process. When the British Museum refused to cooperate in a demonstration project, IDA staff used smartphones and tablets to scan the collection in the gallery without permission.

Shifts in public opinion are also raising new questions regarding who has standing to call for repatriation of objects and what groups or individuals museums should work with to effect returns. Even as momentum gathers for the voluntary restitution of the cultural heritage of Benin, looted by the British in the 19th century, the Restitution Study Group has challenged how this should be done. Speaking on behalf of descendants of enslaved people living in the United States, the Caribbean, and Britain, the study group argues that these looted materials should not be returned to Nigeria, as the representative of the former Kingdom of Benin, because they represent wealth extracted from Africa by the kingdom through the slave trade. Instead, the group is calling for ownership of the relics to be transferred to descendants of people enslaved in the region. How might this campaign affect how museums proceed with voluntary repatriation and who they deal with in negotiating returns?

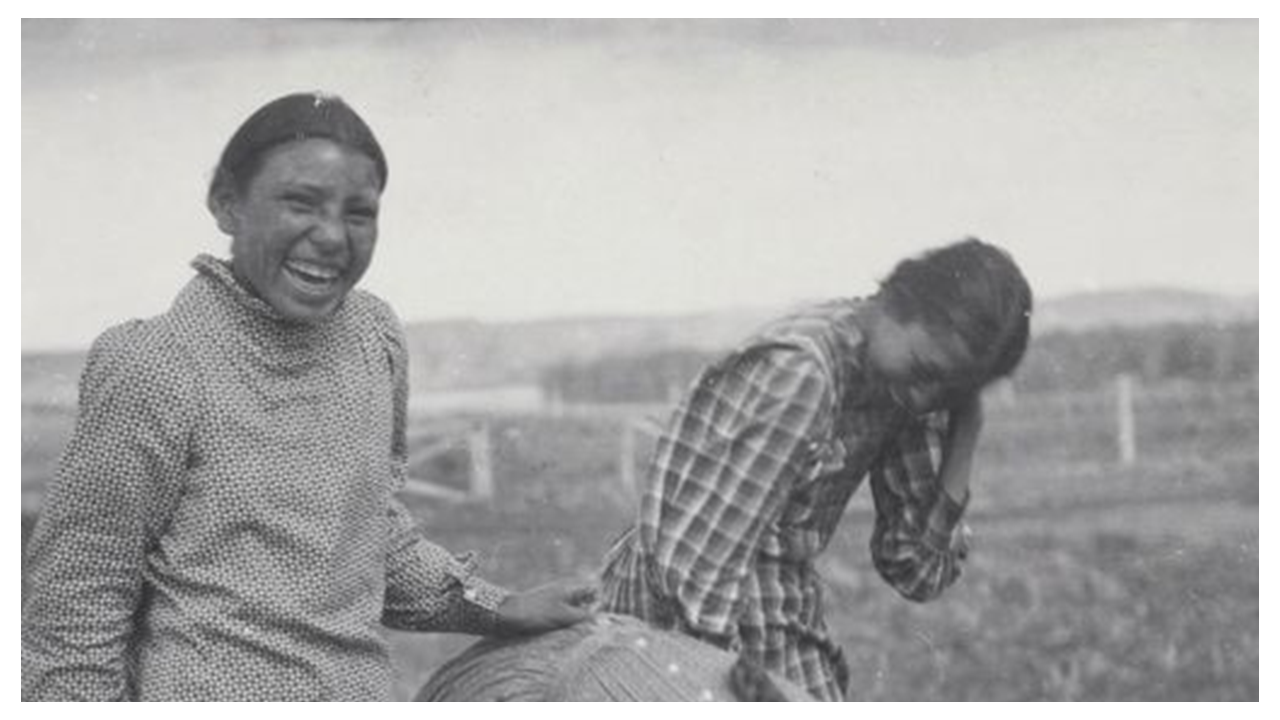

In 2019, Connecticut resident Tamara Lanier sued the Harvard Museums, asserting that the museum should transfer to her historic photographs depicting her enslaved ancestors. While the courts rejected this claim, they allowed that the claimant has a plausible case for damages related to emotional distress caused by the museum’s ownership and use of the photographs. Might this case hold broader implications for other historical images in museum collections?

Reparations Rethought

Finally, the conversation around reparations is growing beyond the ownership of material, per se, to a consideration of what is owed to countries and individuals harmed by past appropriation and exploitation. The city of Oakland, California, is in the process of granting a “cultural conservation easement” for five acres of a city park in perpetuity to the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, an Indigenous women-led nonprofit, and the Confederated Villages of Lisjan. In 2020 the Yale Union arts center in Portland, Oregon, voluntarily transferred its land and building to the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation in what the governing board characterized “a radical act of decolonization.”

While calls for financial reparations are most frequently directed at governments, some museums are taking action on this front as well. The Mattress Factory—a contemporary art museum in Pittsburgh—is implementing an artist-led project to pay financial reparations to selected residents for displacement and gentrification caused in part by the museum. How might museum reparations take the form of power sharing over appropriated resources, whether collections or land?

The attitudes and legislation defining rights and ownership are changing. The debate is swiftly moving from what museums are allowed to do to what they should do, up to and including sharing power and decision-making about the assets they steward, return of those assets, and reparations for past harm. Where will that arc take us a decade hence?

Museums Might …

Start by ensuring the museum is in compliance with all current local, national, and international law. Review collections and establish a process for flagging any objects with unclear provenance or that might be subject to legal claims for repatriation.

- Engage the board and staff in discussing the following questions:

- Where does the organization currently lie on a spectrum of action that encompasses legal compliance, voluntary repatriation of collections, and reparations for damage inflicted by the museum or by society?

- How might the museum work productively with communities and individuals who self-identify as having a moral, cultural, or legal claim to collections?

- Where is there agreement, or disagreement, on the values that should guide the museum’s decisions regarding ownership and control of cultural heritage?