After twenty years of working in museums, I’ve seen all sides of the field—the good, the bad, and even the ugly. But regardless of the negative experiences, my hopes are still as high as when I began my career. I still believe deeply that museums can and should be happy and healthy places to work.

If anything, they should be better places to work than average, given the nature of their missions. Museums are designed to spark curiosity and wonder, care for and present manifestations of creativity, share intellectual achievement, record our existence on this planet, and serve as anchors of learning within a community. Working toward those values should naturally be a joyful, meaningful experience.

And yet, even as more museums are embracing an audience-centered, community-oriented approach, where people (namely visitors) come first, the staff experience does not always seem to be improving at the same time. Stories continue to abound of dissatisfying and even toxic environments, in which colleagues and managers are unkind, unsupportive, and even abusive.

So, why are museums—despite namely being about learning, well-being, and inspiration—sometimes unhealthy places to work? The answer lies in the foundations of the museum field, and the solution lies in emotional intelligence.

Debunking the Myths

Many of the issues in our field stem from myths about what makes a successful workplace that have proliferated for generations. Only by dismantling these false beliefs can we resolve the disconnect between our values and practices.

The first myth we must overcome is that content expertise, technical skills, or intellect naturally make someone a great employee or manager. These qualities are important, of course, but they are the baseline, not the indicator, of success. Research shows that 90 percent of the competencies that differentiate outstanding from average employees relate to the realm of emotional intelligence, like the ability to remain calm under pressure, resolve conflict effectively, and practice empathy. But in the museum field, which for a century has privileged knowledge and intellect above all else, these are not skills that most employees are trained in or evaluated on.

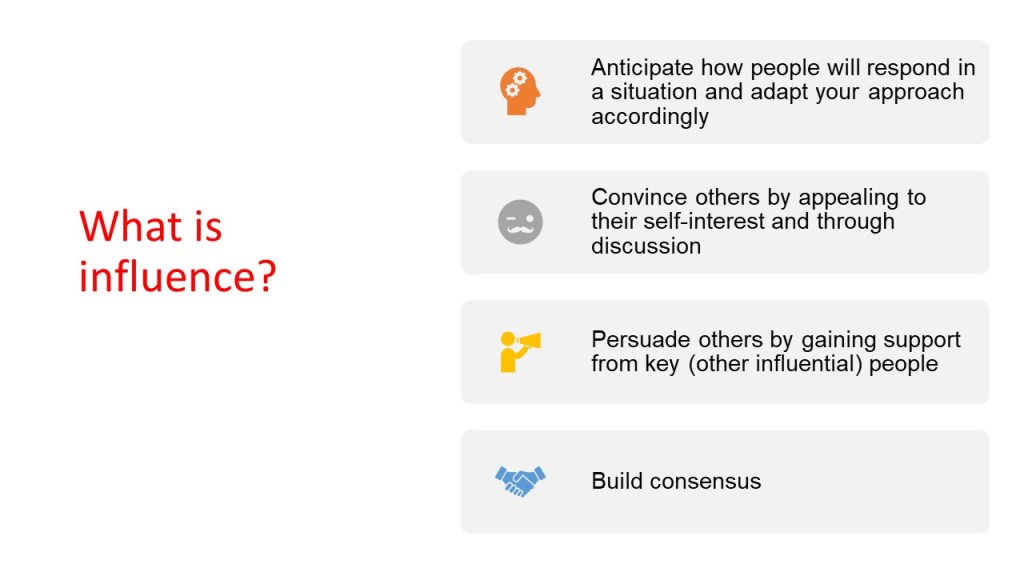

The second myth we must overcome is that authority equals influence. While leaning on hierarchical power can achieve results in the short term, those results are rarely sustainable without the genuine faith of the people you work with. True influence is developed through trust, investment in relationships, respecting the unique contributions of others, building consensus for ideas, and positivity. To influence others effectively and sustainably, you must understand yourself, have empathy for others, and know how to genuinely engage with others.

Unfortunately, lack of training in these tenets of strong leadership has resulted in generations of museum employees unprepared to navigate the complexities of cultivating successful professional relationships. But not all is lost. Human beings have a unique capability that can repair the field—emotional intelligence.

What is Emotional Intelligence?

Humans are first and foremost emotional beings. Though the exact science is still unsettled, there is considerable evidence that our biology plays a significant role in how we feel and behave in response. Beginning in the 1990s, social scientists began to explore whether facility in understanding these emotions could be measured in the same way that knowledge and reasoning are with IQ tests. This concept of “emotional intelligence” rose to broader cultural consciousness beginning in 1995, when psychologist Daniel Goleman published his book Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ.

At its most basic, emotional intelligence means the ability to recognize both one’s own feelings and those of others, and to manage emotions within oneself and in relationships with others. There are many models of the concept, but in my work I have found the most resonance with the one outlined by Goleman and his writing partner Richard Boyatzis.

Many of these models describe the brain as consisting of two systems. System 1 is fast-reacting; it is constantly looking for perceived threats and responding to them emotionally. System 2, on the other hand, is slow, logical, and rational. But because system 1 is the older of the two, embedded deeply in human DNA as a survival mechanism, it is first to react and harder to ignore. Learning to regulate emotions means taking the time and effort to wait out these instinctive reactions long enough for system 2 to kick in and modulate them. This is what emotional intelligence is all about.

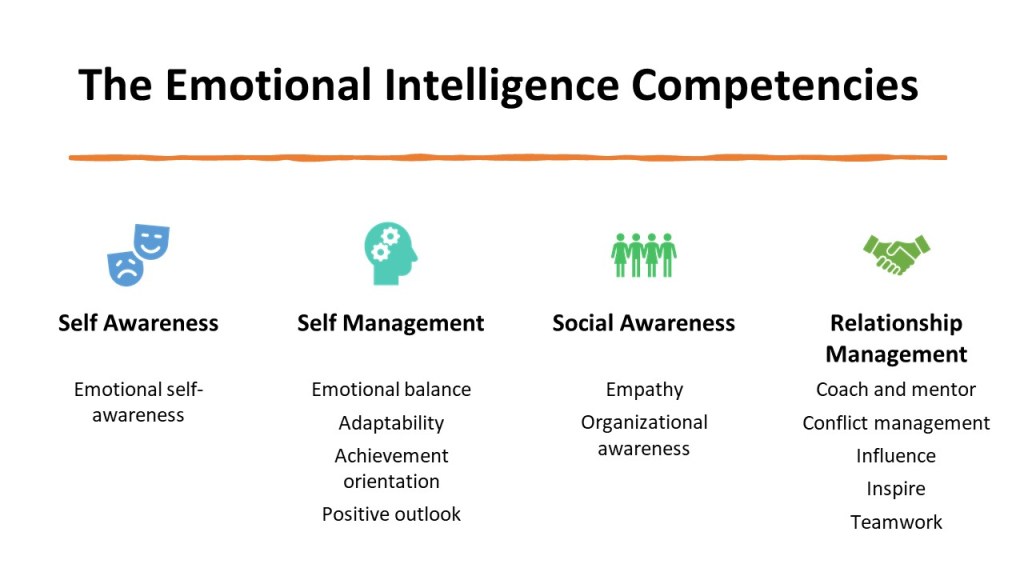

According to Goleman, there are four aspects of emotional intelligence: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management. He has articulated the competencies embedded with each of the four areas as follows:

It Is All about You: Self-Awareness

Self-awareness may just be the most important aspect of being a successful leader. In order to understand others and manage your relationships with them, you must first understand yourself. Self-awareness is about acknowledging your own emotions, the reasons behind them, and how they impact your behavior. A self-aware person is attuned to how others influence their emotional state, while also recognizing the implications of their emotions and behavior on others.

An emotionally intelligent person knows their own strengths and limitations, can articulate their core values and purpose, and is open to honest feedback (both positive and negative). A self-aware person presents themselves to the world with self-confidence, especially in the face of stress or opposition.

Because self-awareness is a combination of understanding yourself internally and how others perceive you externally, the best way to cultivate greater self-awareness is through reflection and gathering feedback.

Beware the Amygdala Hijack: Self-Management

Despite how intense they may feel, emotions are temporary. Acknowledging this fact, and waiting to react until the intensity dissipates, is key to self-regulation. This self-regulation is especially important in a professional environment, so that you can handle stress in a calm way, avoid acting on reckless impulses, and remain poised and positive even in challenging situations. But to build these skills, you must contend with what Goleman calls the “amygdala hijack.”

The amygdala is a small part of the brain that plays a key role in defining emotions and storing memories. This includes triggering what is known as “fight or flight” response—believed to be a hold-over from our earliest days as humans when any perceived threat likely meant life or death. This protective response can be useful in some situations, but in modern life, it is often triggered for threats that are much less serious. It is a rare occasion that in museum work, for instance, a situation is literally life or death. So, why can’t we always keep our emotions and behavior in check at work? Why do we lose control?

The answer, according to Goleman, is because information enters the amygdala milliseconds before it reaches the neocortex, where complex and rational thought takes place. So, even before system 2, that rational part of the brain, can figure out if something is a real threat, system 1 has caused an overreaction. This phenomenon is known as the amygdala hijack.

If you struggle with managing these overreactions, one way to hone self-regulation is to reflect after experiencing them. This way, you can come to recognize what sets off an overreaction and be better prepared to avoid it next time that type of situation occurs. In the long run, this personal reflection can make a major difference in the overall health of a workplace, preventing the toxic group dynamics that derail teams and lead to dissatisfaction.

Empathy and Connection: Social Awareness

A key factor in shifting organizational culture is social awareness, and its close cousin, empathy. Socially aware people respect and relate well to people of diverse backgrounds and perspectives, while demonstrating a genuine care for what others are going through. In working to understand other points of view, they listen attentively to others. They consider the reasons for another person’s behavior, acknowledging that there is something below the surface of it. They pick up on what is being said, and what is not being said; they are able to “read the room.”

Social awareness is essential for working successfully with others. Some of the traits most closely linked to ineffective leadership—like insensitive and abrasive behavior, a cold and detached demeanor, impulsive decision-making, and arrogance—come down to an inability to read the room and understand what others you work with may be feeling.

Building Empathy for Others: Think about the most difficult colleague you have. Take a moment to consider why you find them so difficult to work with. Now, flip the narrative…imagine you are that person. What challenges and pressures might they be experiencing that is causing their behavior? How might you reconsider your relationship with this person with this new insight? And how might you navigate that relationship differently if you approach it with empathy?

Influence: Relationship Management

The fourth and final competency of emotional intelligence is relationship management. In effective relationship management, emotionally intelligent people use their understanding of themselves and others to develop and navigate successful relationships, with a spirit of generosity.

This is especially important for anyone that manages other people. It is not just about getting along well with others, but acting with sensitivity to the feelings of the people you are dealing with. In other words, you learn to modulate your behavior with different people based on their self-interest and the context of the situation. Relationship management is about influence.

Relationship management is also about direct communication, transparency, coaching, and mentoring. The emotionally intelligent person does not shy away from conflict, but handles difficult conversations effectively—directly, and with confidence and compassion.

Those that have mastered these skills are genuinely inspirational leaders. They sense other’s needs and perspectives and guide them towards goals in a way that meets their needs.

Creating Happier and Healthier Museum Work Environments

While IQ, a traditional measure of intellectual ability, can be important for measuring someone’s content knowledge or skill level, emotional intelligence far outweighs IQ as an indicator of success and performance, at all levels within an organization, but especially in leadership. Being emotionally aware of oneself and others, and better understanding what drives behavior, is the foundation of healthy relationships and successful work environments.

Emotional intelligence is not just about likeability and sensitivity to others. It is also about having the courage and capacity to drive change. Staff at all levels within an organization have the ability to do this, working to disrupt the pervasive myths and structural deficiencies in our field and replace them with healthier alternatives. Through an accumulation of small acts, together we can accomplish these big changes.

Here are some of the ways you can help to promote emotional intelligence at your museum:

- Hold staff accountable for their behavior. Regardless of the content expertise someone may have, we must not excuse or normalize misconduct. While this is primarily the responsibility of leaders and managers, we can all play a part. For example, when we are confronted with toxic behavior ourselves, we can start by refusing to accept or engage with it, such as by leaving the room and reporting it to a supervisor. Emotional intelligence is not about suppressing emotions and suffering through abuse, but rather maintaining integrity and not letting the bad behavior of others influence your own.

- Work on yourself. Start the process from within by building your own self-awareness and your connections with colleagues. Take time to reflect on your interactions with colleagues, especially in difficult situations. Find ways to understand them, both as co-workers in the office and as people outside of work. For structured support, consider working with a career coach, who can support you in achieving your definition of success.

- Invest in emotional competency. If you are a leader or manager, prioritize training opportunities for your teams that explore skills beyond the typical content focus, such as team-building, communication, and management. Also build in time for your team to get to know each other beyond the tasks of their jobs. If you are not yourself a leader or manager, let your supervisors know that you would be interested in these opportunities.

Excellent Advice on an important topic!

Very helpful analysis with practical suggestions and insightful observations of the complex museum work environment today. Thank you.

Thanks Jen. Extremely well done and great advice. Best,