This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s July/August 2023 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

The Amon Carter Museum of American Art is engaging students in inclusive discussions of artworks where diversity is not necessarily apparent.

In the museum field, we recognize that inclusive teaching is important. Institutions have taken great steps to rectify historic inequities, including diversifying their collections and exhibitions.

The Amon Carter Museum of American Art, an institution located in Fort Worth, Texas, that originated with a Western art collection highlighting the works of Frederic Remington and Charles Russell, is focused on collecting works and presenting exhibitions that reflect the breadth of American art. Recent acquisitions, including work by Hank Willis Thomas, Anila Agha, and Shelley Niro, support museum educators in providing inclusive instruction. However, such acquisitions do not eliminate the need to reflect on our teaching practices related to the other artworks that comprise the bulk of the collection—pieces where diversity is not readily apparent.

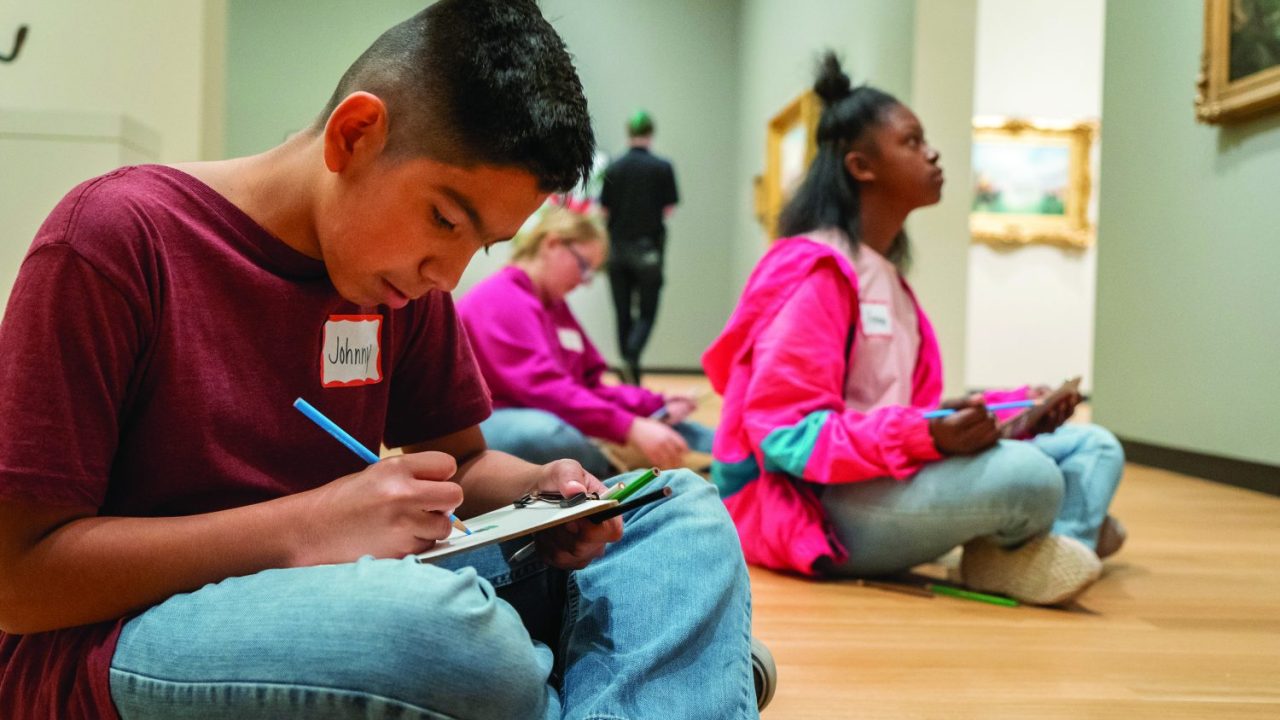

The Carter welcomes 15,000 elementary and secondary students on guided tours each year. Our museum staff includes 19 members of the education team. Of that team, eight members specifically focus on in-gallery programs for pre-k–12 students and educators, which include inquiry-based tours and collaborating on the creation of student program content. Beginning in 2019, Carter gallery teachers began developing new strategies for infusing diversity, equity, and inclusion into their instruction, as exemplified in the three works discussed here. These artworks are a selection from the teaching content we create each year and would not necessarily be taught together, but they reflect an overall, long-term transition in how we look at and teach the artworks in the Carter collection.

The Hunter’s Return

A perennial favorite artwork for student tours is Thomas Cole’s The Hunter’s Return (1845), shown on p. 26. In this oil-on-canvas painting, two men approach a log cabin from an autumnal forest carrying a deer. Women and children greet them from various places around the homestead; their efforts caring for the home are on display in the form of drying laundry, a well-tended garden, and a chimney with smoke indicating a fire.

In prior years, gallery teachers would have focused on the labor of these individuals and why this family would select this site for their home. In some ways, the lesson related to this artwork was one of the easiest to refine, as the work’s reference to manifest destiny invites discussion of the impacts of settler colonization. In reassessing our focus with this artwork, we developed the following questions to elicit meaningful student engagement. The questions can be explicitly stated or implicitly addressed through questions tailored to the audience’s developmental level.

- What did the artist include in this painting?

- What is the meaning or symbolism of these present elements?

- What did the artist choose to exclude from this painting?

- Considering the artist and the context of the time in which they lived, what message is being communicated?

Our students are primed to call out the obvious: the exclusion of Indigenous communities from this view. We then recognize the many nations that lived in the areas in New Hampshire, New York, and Connecticut that Cole used as inspiration for this painting: the Abenaki, Tuscarora, Oneida, St. Regis Mohawk, Onondaga, Seneca, Cayuga, Tonawanda Band of Seneca, Poospatuck, Shinnecock, and Mohegan.

As we walk students through the questions, we invite them to map out their responses visually. We provide a sheet of paper, or a reproduction of the artwork, and ask students to note the significant elements. They then overlay tracing paper to identify the meanings of each component and add excluded elements. Each time we complete this activity, new ideas come to light, which is exactly the point. Students bring their lived experiences into the museum, make meanings, and share their wisdom with their peers.

After inviting students to look critically at the artist’s perspective, we provide supplemental images and information on the Indigenous communities that inhabited these lands prior to white settler-colonists. We discuss how Indigenous communities used the land’s resources and how that influenced the settler-colonists who came later. It is essential to acknowledge the wisdom provided by Indigenous communities that allowed white settler-colonists to build the United States empire.

Ranchos Church, New Mexico

As important as it is to have students critically consider an artist’s framing of a subject or theme, it is also important to interrogate how we as museum educators frame topics and themes. As we reassessed our “Engineering in Art” programs, we noted a bias toward Western industrial structures. To refine this program, we identified a new objective: providing students with other perspectives of what design could be and is intended to accomplish.

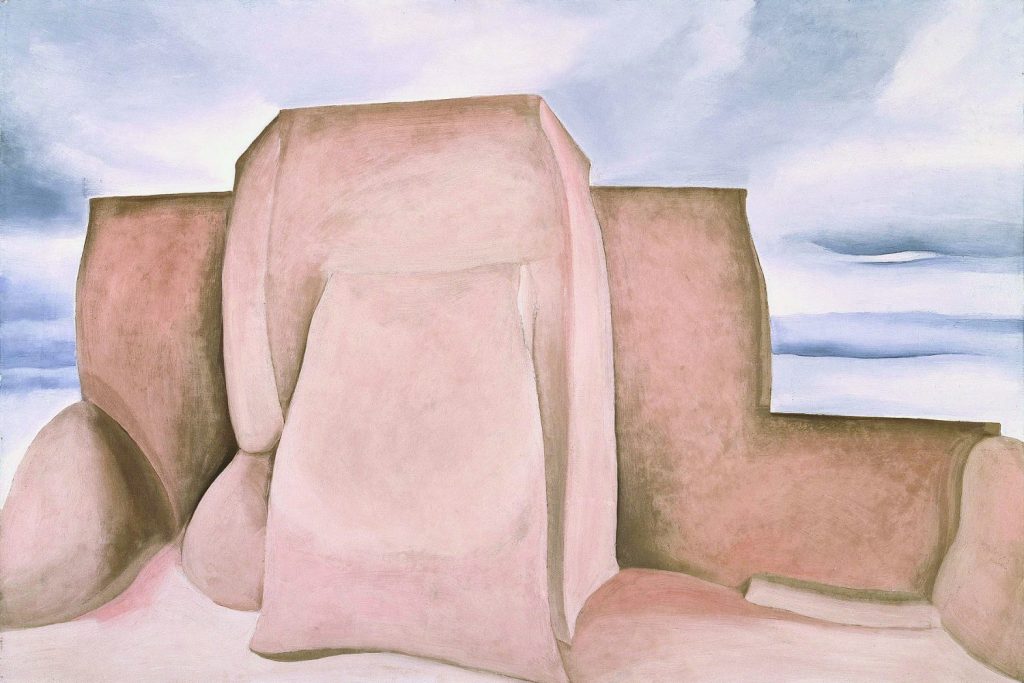

Thus, we added a new artwork to the program, Ranchos Church, New Mexico (1930–31) by Georgia O’Keeffe, shown above. In this oil-on-canvas painting, we see a rear view of San Francisco de Asís Mission Church, located near Taos, New Mexico, set against a cloudy sky. In our discussion, we want students to engage with the following questions.

- What is the purpose of engineering?

- What materials and processes have communities developed to respond to their particular needs?

With this artwork, we are able to zoom out from buildings in metropolis centers that often reflect Western priorities and values. While urban structures are impressive and worthy of discussion, what is ideal for one community is not ideal for another.

In the case of San Francisco de Asís Mission Church depicted in the painting, we discuss how adobe brick has many advantages for the community where it is found: it is strong and environmentally responsible and offers thermal regulation. For maintenance, the community comes together each year for the Enjarre, or remudding, of the church. While another design with modern, industrial materials could be sought, the heritage and community-building provided by this adobe design remains desirable for this church.

Conversation—Sky and Earth

Charles Sheeler’s Conversation—Sky and Earth (1940), shown above, is another artwork that lends itself to discussing community needs. In this oil-on-canvas painting, an electrical transmission tower dominates the foreground, with the Hoover Dam and an intensely blue sky filling the background. This painting highlights the might of the United States industrial complex at the outset of World War II, conveying the nation’s power through its distinctive vantage point from below the tower.

Prior lesson plans with this work emphasized the purpose of the Hoover Dam and the technological achievements involved in its construction, which remain important talking points. But the museum’s acquisition of Cara Romero’s Water Memory (2015) has helped us expand this conversation with students. The work is an inkjet print showing two Santa Clara Pueblo corn dancers suspended in dark, blue-green water. Romero, a member of Chemehuevi Indian Tribe, draws attention to the displaced Indigenous communities whose lands were flooded to erect dams.

With this in mind, we reviewed our lesson plans for Sheeler’s Conversation—Sky and Earth to include conversations about how decisions are made related to resources. Essential questions, like the following, underpin these conversations.

- How are the needs of multiple, diverse communities balanced, particularly when planning for infrastructure and land development? Specific to this image, why were the water needs of some placed above the needs and rights of others?

- How does the placement of certain industries impact communities?

- How do we balance short-term benefits (water access for growing urban centers) and long-term consequences (displacement of communities)?

There are no neat answers to these questions, and that is fine. Our goal is to have students grapple with the complex experiences of life in the United States, past and present. Admittedly, these are high-level, abstract questions. To scaffold this down, especially for upper elementary and middle school audiences, we ask students to think about where they live. What resources are found in their community? What resources would they like greater access to? Are there elements that they believe do not serve their community’s interests? Connecting to the students’ lived experiences is where the magic happens. We are honoring the diverse knowledge that students can contribute to conversations about the artworks.

You may be wondering why we would not just teach with Romero’s photograph instead of Sheeler’s painting. If the institution is actively collecting works of art by artists of color or from marginalized communities, why would the education team not utilize them for gallery tours?

The reality is that many of these new acquisitions are photographs or works on paper with limited time permitted for display due to preservation needs. While newer acquisitions by contemporary artists rotate on view, the contributions of white male artists primarily working in painting and sculpture remain the bulk of displayed artwork at the Carter. These works provide a rich opportunity to model for students new ways of critically engaging with art, history, and the many narratives that are created and perpetuated in the past and present United States.

The Journey Continues

With every lesson we facilitate, we need to critically examine what narratives are present and what narratives are absent. We are looking into the gaps, in the collection and the instruction. When a gap is present, we have an opportunity to establish new strategies for connection with students.

We have already made progress: 92 percent of educators surveyed between August 2022 and February 2023 said the discussion and activities during gallery tours allowed students to connect their lived experiences to American art and artists’ stories.

It might seem easier to have diverse and inclusive conversations with artworks that reflect the multiculturalism inherent in the United States, but we remain committed to intentionally having these conversations with any and every artwork. Doing so requires us to reflect on underlying assumptions, ask new questions, decenter familiar stories, and share authority with the students we serve.

Tips for Offering More Inclusive Education

Many perspectives are needed to create diverse and inclusive content. This can include staff, invested classroom educators, or community partners.

It’s easy to fall into old patterns and strategies. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel each time, but you should always be open to innovating and improving.

Be true to the collection you have, but acknowledge the context in which those artworks exist.