This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s September/October 2023 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

When we welcome diverse backgrounds and perspectives, we can increase our reach, relevance, and impact.

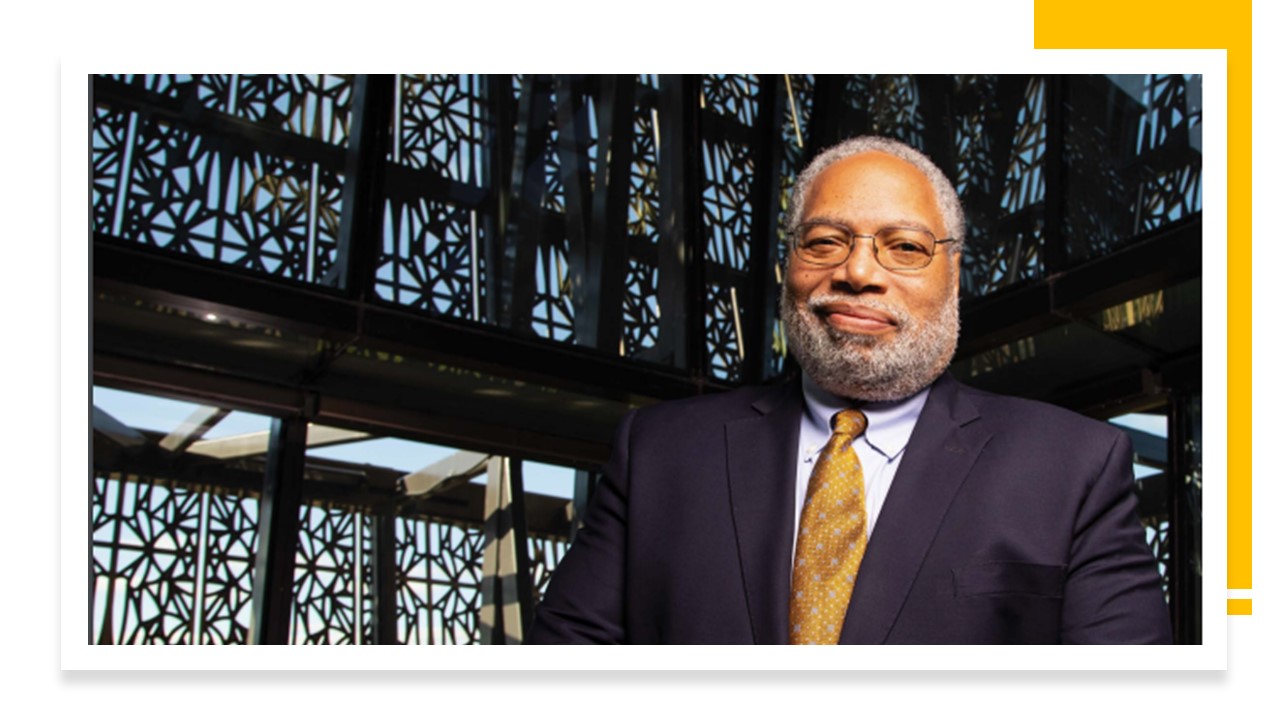

Countless times at the dinner table growing up, my father would tell me, “Only fools believe they have a monopoly on wisdom.” As I was creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture, his words echoed in my memory, guiding me as they had done so often during my unexpected career in museums. Besides its personal significance, his advice also teaches a universal lesson about how our organizations can more effectively serve the greater good.

Museums protect cultural heritage, conduct important research, disseminate knowledge, and create fascinating exhibitions and educational programming. The way our cultural institutions have stepped up recently in times of great need—during the pandemic, in response to climate change, addressing racial and social inequities—attests to their power to do good in the world. But it’s only when we listen to others that we can become more than community centers and truly reside at the center of our communities.

We must embrace the collective wisdom generated by diverse backgrounds and perspectives. We must challenge our assumptions about the way museums have operated in the past. And we must listen to all. By doing so, we can be respectful of tradition without being bound to it.

Broadening Our Perspectives

The origin of museums can be traced to the “cabinets of curiosities” or “wonder rooms” of the early 17th century. These spaces, created by wealthy elites and featuring a wide variety of art, natural history specimens, and religious artifacts, were inaccessible to the public. They were antithetical to my father’s axiom, knowledge doled out from on high to certain audiences.

It wasn’t until English antiquarian Elias Ashmole donated his wonder room collection to Oxford University in 1682, creating the Ashmolean Museum, that the template for modern museums was created. In the 18th century, other public museums, like the British Museum and the Louvre, followed suit. Still, they weren’t representative institutions in the way modern museums are. Access was typically limited to privileged white men, their collections often acquired in unethical ways rooted in colonialism and racism. Moreover, employment within these museums was largely inaccessible for women and people of color.

By the time I was hired by the Smithsonian as an education specialist at the National Air and Space Museum in 1978, museums were more open and attentive to diversity, but it was clear that much still needed to be done. In 2000, I wrote an essay for the American Alliance of Museums’ (AAM) publication Museum News that detailed some of my thoughts on the changes needed to prod our field in the right direction: tying accreditation and funding to diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI) benchmarks; increasing opportunities for minority candidates to enter the museum field; and leveling the playing field for women and Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) in cultural institutions.

A pivotal moment for the museum field came during the 2020 protests about George Floyd’s death. Museums across the country were galvanized and made commitments to become more diverse and inclusive institutions. And it wasn’t just rhetoric; we’ve followed through. According to a 2022 Mellon Foundation survey of art museums, the representation of people of color (POC) on staff increased by nine percentage points, from 27 percent in 2015 to 36 percent in 2022. Notably, there was a seven-point increase in POC representation among conservators, curators, and directors and an eight-point increase in women in museum leadership, rising from 58 percent to 66 percent. Moreover in 2021, 45 percent of newly hired employees identified as POC.

I’m proud to say that AAM is leading the way in making a robust push for a more diverse profession. Last October, it unveiled a multiyear DEAI initiative to transform the standards that guide museums’ best practices and accreditation. The results will be the first update to standards across the museum field in two decades.

Assessing Our Collections

As a historian, I’ve always felt that to make progress as people, as nations, and as institutions, we must be willing to truthfully examine our history. At a time when many history books and curricula are under attack, it’s more important than ever. As stewards of heritage and history, cultural institutions have a special obligation to honestly appraise the past. To do so, we must first look within.

In recent years, museum collections have increasingly come under scrutiny. It’s up to us to assess what we have, how we acquired these items, and whether they are still worth having. Scholarship and educational value can no longer be the sole determinants of what we keep in our collections. If objects under our care were acquired unethically, no matter how long ago, we are obligated to assess whether they belong to other communities, not only legally but morally. We must glean the wisdom of source communities, actively listening to their guidance and engaging in good-faith efforts to respect their culture and address their concerns.

At the Smithsonian, we instituted a comprehensive ethical returns and shared stewardship policy that authorizes Smithsonian museums to return collections to their communities of origin based on ethical considerations, including how they were originally acquired. By acknowledging and rectifying our historical missteps, by forging more equitable relationships with source communities, and by putting ethics first, all of us can better embody the nation’s ideals of fairness and justice.

Engaging New Audiences

We should also seek wisdom from people who have traditionally been underserved by museums. The proliferation of new technology has made that more achievable than ever. I think of all the examples of museums making their exhibitions and educational offerings accessible during the height of the pandemic. For example, Toronto’s Van Gogh immersive exhibition of massive, projected artworks was turned into a drive-through experience so people could safely enjoy it from their cars.

Outreach by more traditional means can also make our institutions more accessible to people outside our normal spheres of influence. The Smithsonian is working to reach more rural areas of America, including through a partnership with 4-H clubs and our affiliate museums throughout the country, to share resources about democracy and civics, DEAI, STEM learning, and career development.

If we are to have greater reach, relevance, and impact in the years ahead, we must continue to connect with people where they are, whether through cutting-edge technology or through old-fashioned networking, collaboration, and creative programming.

When I was a child, my interest in museums was sparked during a road trip from our home in New Jersey through the still-segregated South. I was already enthralled with history and asked my dad to stop at some of the Civil War sites along the way. Aware of the risks we could face due to the color of our skin, my father made the difficult decision to decline my request. However, on the way back home, he took a detour into the nation’s capital and brought me to the Smithsonian. He explained that this was a place where we could learn about science, history, and culture without worrying about being treated differently.

The experience was life-changing, leaving me with an enduring sense of wonder, possibility, and belonging. It’s a reminder that any interaction with a visitor, online or in person, presents an opportunity to foster such connections. And it’s a reminder that no matter how well established our institution or how venerated our reputation, we can continually expand our capabilities by seeking out the wisdom of others.

Resources

Lonnie G. Bunch III, “Flies in the Buttermilk: Museums, Diversity, and the Will to Change,” Museum News, July/August 2000

aam-us.org/2019/05/29/flies-in-the-buttermilk-museums-diversity-and-the-will-to-change/

Liam Sweeney, Deirdre Harkins, and Joanna Dressel, Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey 2022, Mellon Foundation

bit.ly/42JPss6