This excerpt is adapted from TrendsWatch: Museums as Community Infrastructure. The full report is available as a free PDF download.

“I don’t know why people feel unhappy when the curve of a graph fails to keep going up, but they do. Even when we find something we’d like to reduce, such as highway fatalities, it doesn’t always sound as though we had our heart in it.”

—E.B. White, author and editor

One of the greatest threats facing society today is unsustainable growth: the inequities, damage, and instability created by systems fueled by a philosophy of “more is better.” To date, museums have largely shaped their behavior around for-profit values of power, productivity, and economic metrics of success. As a result, success is often measured by increasing attendance, growing collections, and expanding facilities. But as nonprofits, museums have the freedom to experiment with other models. How can they challenge the paradigm of perpetual growth and model what it looks like to build healthy, sustainable systems based on values of public service?

The Challenge

In the past half-century, as the global population broke record after record, the Western world began to grapple with the realization that unconstrained growth—whether of consumption, tourism, communities, or organizations— is unsustainable. This realization was captured in Limits to Growth, a 1972 report commissioned by the Club of Rome, based on computer modeling of five key resources: population, food production, industrialization, pollution, and consumption of non-renewable natural resources. The study’s mathematical models generated three scenarios, two of which foresaw civilization burning through all available resources, resulting in the collapse of civilization in the last half of the twenty-first century. Only the third, in which humanity significantly restricted its resource consumption, resulted in a stable state. Now it is becoming clear that the limiting factor to growth might not be any of the specific resources that Limits to Growth examined, but the cumulative effect of human activity on the climate.

On an accounting sheet, growth often seems profitable because many of the underlying costs are offloaded onto ecosystems, vulnerable communities, or society in general. These costs, called “negative externalities,” may be environmental (i.e., waste, pollution, and degradation) or human (i.e., worsened public health and precarity of employment). This formula creates systems that may succeed in the short term as measured by narrow financial metrics, but are in the long term destined to fail, bequeathing the externalized damage they’ve done to future generations.

As the axiom states, you get what you measure, and if the primary measure of success is financial profit, companies are incentivized to minimize costs to improve the bottom line. One of the principal costs is labor, and left to themselves most businesses, particularly large publicly traded companies beholden to stockholders, will try to minimize wages and maximize the flexibility of their workforce. But subpar wages and precarious work fuel profits while undermining the economy overall, and local communities in particular. In 2020, the Government Accountability Office issued a study showing that taxpayers effectively subsidize the low wages of major employers including McDonald’s, Amazon, Uber, and CVS through services like Medicaid and food stamps. These companies are in effect relying on society to cover the externalized costs of their labor.

Nonprofits in general, with museums being no exception, generally buy into the dominant for-profit model of success. In the quest for appropriate “KPIs” (Key Performance Indicators), museums have become accustomed to reporting things that are relatively easy to measure: attendance, number of items added to the collections, dollars raised in a capital campaign, and square feet of new space. The assumption, stated or unstated, is that success means making these numbers go up. But museums are beginning to grapple with the realization that success lies not on an increasing trendline but somewhere on a numeric bell curve. There is actually such a thing as too much: Too many visitors—to the point the press of the crowds degrades the experience, puts undue stress on staff, and in some cases endangers the collection or the site. Too many collections—to the point that the number of objects exceeds the capacity of museums to care for or make use of them. Too big of a building—to the point that the cost, though a powerful lever for fundraising, does not justify the benefits it provides to the community.

Nonprofit museums are especially vulnerable to economic imperatives that favor outputs at the expense of labor. While there is a clear moral case to be made for prioritizing people over profit, low wages in the nonprofit sector can be framed as prioritizing mission, and the public good, above all. (This has been variously referred to as “the systematic starvation of those who do good” or the “nonprofit culture of poverty.”) This attitude has been reinforced by a complex mix of history and funder expectations. The nonprofit workforce has long been predominantly female, so nonprofits inherit the gender inequities attached to compensation. For many decades, donors and funders were trained to see “overhead” (largely comprised of staff salaries) as wasteful spending, and to look for a low ratio of overhead to programmatic spending as a measure of a well-run nonprofit. The cumulative result has been pervasively low wages, burnout, and high turnover. Long term, the field is grappling with how to institute reforms that ensure museums cover the true cost of working in a museum, rather than expecting individuals, families, communities, and society to cover the gap.

The Response

In Society

Here is a brief round-up of some of the social and economic movements attempting to reframe American attitudes towards growth and develop sustainable measures of success:

Circular Economy

More industries are trying to create “circular economies”—systems of production and consumption that repair, reuse, and recycle materials to the greatest extent possible, in the interest of reducing the use of scarce resources and the generation of waste. A growing number of makers and vendors are using recycled or upcycled materials to produce their goods, and in turn to market their brand. In 2021, the UK passed a “right to repair” law that requires manufacturers to provide parts that support the repair of their products (rather than forcing consumers to discard old electronics and buy new). Almost every state in the US is considering similar legislation, and President Biden recently signed an executive order directing the Federal Trade Commission to make third-party product repair easier. Responding to pressure from shareholders, Apple recently reversed its long-term policies and will start selling replacement parts and tools to make it easier for consumers to make their digital devices last longer than the average four to five years.

Sustainable Tourism

In the past few years, major tourist destinations such as Venice, Barcelona, and Amsterdam have begun to grapple with the downsides of their popularity—overcrowding, unaffordable housing, environmental degradation, and a decline in the quality of life for local residents. In 2018, the mayor of Dubrovnik declared the city would cap the number of cruise ships allowed to dock each day. Venetians have used the pandemic pause in tourism to envision how the city might join the “sustainable tourism” movement by encouraging fewer, longer stays that foster meaningful engagement with art and culture, promote and expand local universities, and build jobs untethered from tourism. In November 2021, the governor of Yucatán signed a collaborative agreement with UNESCO to develop tourism that protects, promotes, and safeguards the cultural and natural heritage of the state. These efforts may presage a larger cultural and economic shift toward thoughtful management of tourism that measures its full costs and benefits.

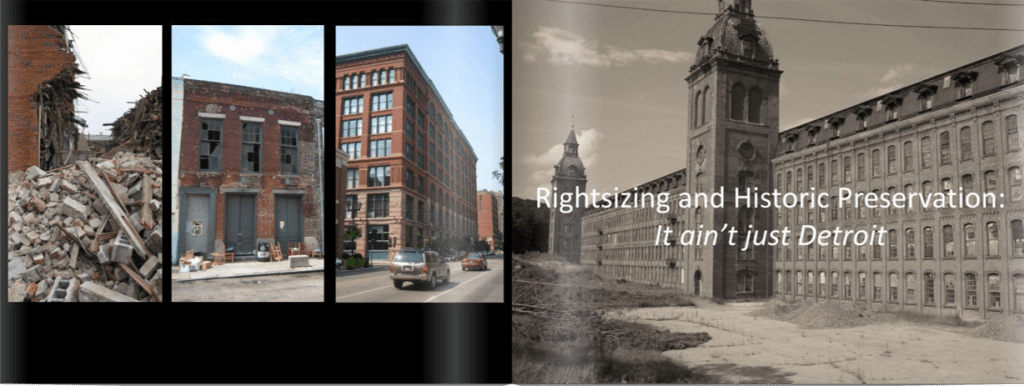

Right-Sizing Cities

At least eighty US cities are shrinking in population, due to shifts in manufacturing, demographics, and economic decline. In some cities, this means demolishing thousands of buildings—in some cases buying out and shuttering entire neighborhoods. Others, such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, are trying to compensate for the collapse of traditional industries by reinventing themselves as tourist destinations. For all these communities, the question is how to “right-size” in a way that minimizes damage to people and to heritage and results in a livable, equitable, sustainable urban landscape.

Reshaping For-Profit Culture

We are seeing a slow shift in the attitudes of corporations from a narrow focus on shareholders to a broader responsibility for “stakeholders.” In 2019, the Business Roundtable issued a statement on “the purpose of a corporation” that, overturning thirty years of precedent, argued that companies should be concerned not only about the profit of their shareholders but also the wellbeing of their employees, the state of the environment, and the ecology of suppliers who support their work. All this in the interest of creating “a more inclusive prosperity.” (The statement is a pointed refutation of the philosophy articulated by economist Milton Friedman in 1970 that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.”)

Employee Wellbeing as a Metric of Success

One important plank in the Business Roundtable statement is a commitment to the wellbeing of employees through fair compensation, training, education, and fostering diversity, inclusion, dignity, and respect. That shift in philosophy may prove to be too little, too late to stave off what is being called the “Great Resignation”— the current swell of people leaving for better jobs, or, in some cases, quitting the workforce entirely. Some of this exodus is the result of people shopping for better wages in a tight labor market, or of stress and burnout during the pandemic, but the Great Resignation is also a rational response to systems that fail to provide workers with childcare, health care, elder care, and affordable housing within a decent commute range of their workplace. This response may accelerate a trend that existed before the pandemic as well—a reset away from “productivity” of work output being the be-all and end-all measure of a good life or a good worker. Even in Japan, where work culture is so hardcore that “karoshi” (“death from overwork”) is an actual thing, reforms are beginning to germinate, with initiatives ranging from caps on excessive working hours to increased flexibility, as well as a requirement for employers to mandate at least five days off work for staff compiling at least ten days of unused leave.

Questioning “More is Better”

The movements described above tackle specific systems, but proponents of “degrowth” argue that we need a larger paradigm shift, from systems that rely on growth for continued success to more sustainable values, notably environmental sustainability and social justice. Proponents envision a future in which people in wealthy countries will learn to “live well with less”: less travel, less consumption, and less impact overall on the environment. Degrowth has allied itself with several movements in which museums are already involved, including decoloniality, slow culture, and the “We Are Still In” initiative supporting the goals of the 2015 Paris Climate Accords.

In Museums

Museums, stressed by disruptions to conventional sources of income, are beginning to challenge their own traditional metrics of success, including attendance, size of collections, and new buildings or expansions fueled by capital campaigns, and to search for meaningful alternatives.

Attendance

Some museums have designed their buildings and experiences around limited attendance in order to provide smaller, more intimate experiences for the visitor. Others have experimented with the practice on an ad hoc basis. During pandemic-induced attendance caps, some museums found that visitor satisfaction rose as crowding declined. Researchers in the attractions industry have suggested that, post-pandemic, visitors may retain a preference for lower density, social distancing measures, and even less interaction with museum staff. If this holds true, museums might follow the lead of cities adopting sustainable tourism: fostering fewer, deeper, longer interactions, providing exclusive experiences, and supplementing admissions revenue with a wider variety of secondary income streams, including digital programs and online merchandise.

Collections

The accretion of unpruned collections can become the museological equivalent of barnacles—a drag on the organizational ship. The museum sector is finally beginning to chip away at the barriers to deaccessioning, not as a source of financial relief, but to rationalize the allocation of resources to produce the greatest good for the public. Besides the logistical barriers (the time and money it takes to deaccession responsibly), this shift requires a cultural change in museums’ measure of success. Acquisitions are a source of pride, while deaccessioning offers few rewards, either financial (due to ethical guidelines for use of the resulting funds) or professional. Some museums are tackling these hurdles and downsizing their holdings; others are slowing growth through joint acquisitions and collections-sharing. Technological advances in the last decade have added an interesting twist to this issue, as museum staff consider how the rapidly expanding universe of accessible digitized collections might influence choices about what to add to the physical collection or archive.

Use of Capital

The cultural sector as a whole is having a moment of reckoning regarding physical growth. In 2012, the University of Chicago’s report Set In Stone: building America’s new generation of arts facilities, 1994-2008 confirmed what many had long suspected to be true: many of the major cultural facilities projects that marked the turn of the century were, in fact, overbuilt and unsustainable. The researchers found that many of the biggest projects (and notably, some of the least successful), were driven by the ambitions of leaders and donors, not by the needs of the community. But overbuilding is a natural result of museum economics. Traditionally it’s been easier to attract gifts associated with naming rights on a beautiful building than for intangible social goods. Despite that handicap, some museums are beginning to ask how capital campaigns can fund improvements to the wellbeing of staff and the community. In the absence of such capital, programs are often dependent on grant funding, and even successful programs that produce measurable good are too often terminated when the grant ends.

Labor

Even before the pandemic, labor conditions and low wages had contributed to the pressures leading to a rise in the number of museum staff seeking to join unions.

COVID-19 dramatized the vulnerability of museum staff in the lowest paid, least stable positions. By fall 2020, pandemic impact had led over half of US museums to lay off or furlough staff, with front-of-house positions being most at risk. At some museums, directors and leadership staff took pay cuts to mitigate the impact; at others staff banded together to create mutual aid funds to support out-of-work colleagues. Post-pandemic, many museums factored job security, wages, benefits, and equity into their plans to rebound and rebuild.

Systems-Level Change

Just as with society, real change for museums will require systemic reform, both of how museums define success for themselves and how they are judged by funders and donors. It seems likely that one reason museums uncritically adopt for-profit measures of success is that their boards of trustees are often dominated by people from the business world. Now there is a national effort, led by organizations that include the American Alliance of Museums and the Black Trustee Alliance for Art Museums, to help museums recruit trustees who bring diverse experiences, perspectives, and values to the boardroom. Boards that reflect the community the museum serves may be more likely to value metrics that track the good a museum does for that community.

The charitable funding sector is addressing the need for systemic change as well. In 2013, GuideStar, BBB Wise Giving Alliance, and Charity Navigator (all major players in the realm of scoring and reporting on nonprofit performance) launched the Overhead Myth campaign to combat the false conception that financial ratios in general, and overhead “efficiency” in particular, are an appropriate measure of overall nonprofit performance. Museums can accelerate this reform by preemptively adopting better metrics of success, adding to the yardstick of “service to mission” measures that challenge them to maximize community wellbeing.

Museum Examples

Attendance

Even after a major expansion in 2018, the Glenstone museum in Potomac, Maryland, implemented timed ticketing to limit attendance to about four hundred people a day in order to provide a contemplative experience conducive to deep engagement with the art in its building and on its grounds. Starting in 2021, Old Salem Museums & Gardens and The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts began limiting school groups visits to three days a week, with a cap of three hundred students per day. The strategy is to spread out the school visitation over many days (with fewer students), which in turn will require less staff all while providing a better visitor experience. Extensive analysis of operational data convinced the museum’s leadership team that directing the visitor engagement to a manageable scale was a far better operations model than the previously held “bigger is better” and “be everything to everyone at all times” model.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic forced attendance limits on museums, the Vatican and the Louvre took steps to limit visitation because over-tourism was degrading the experience, stressing staff, and in some cases damaging historic structures. In 2021, the Uffizi Galleries in Florence, Italy, launched the “Uffizi Diffusi” (“Scattered Uffizi”) initiative to reduce overcrowding in their historic palaces and distribute tourism more broadly in their region by pushing treasures from their collections outside their galleries and into other parts of Tuscany.

Collections

The University of California, Irvine’s recently formed Institute and Museum of California Art (IMCA) is making collections-sharing a core aspect of its operation and mission. In support of this strategy, the museum’s plans include building a “technological, logistic, and collaborative platform” that will facilitate sharing across academic, municipal, and private art museums. The museum’s “founding ambition” document envisioned this platform as a way to to “overcome the traditional protectionist tendencies of most collecting institutions.”

In 2015, the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields embarked on the Collections Ranking Project initiative to assign letter grades to each of the fifty-four thousand items in its collections. Items receiving a rank of “D” (approximately 20 percent of the collection) were flagged for potential sale or donation to another institution. (The alternative would have been to spend about $14 million to double the museum’s storage space.) As of 2019, the museum had deaccessioned 4,615 objects, the vast majority through sale, and transferred 124 objects to other institutions. In 2018, History Colorado embarked on a similar project to survey, assess, and refine (i.e., downsize) target areas in the museum’s 225-thousand-artifact collection.

Using Capital for Sustainable Good

In February 2021, the Baltimore Museum of Art announced it had secured $1.46 million in private gifts to fund DEAI initiatives. $110 thousand were dedicated to raising the base salary of fifty workers from 13.50 to fifteen dollars an hour, with a goal of raising base pay for guards and visitor service personnel to twenty dollars per hour by the end of 2023. In November, the Toledo Museum of Art announced it had received two bequests totaling $2.5 million, dedicated to employee professional development and engagement.

In March 2020, the Yale Peabody Museum in New Haven, Connecticut, closed to the public for an extensive renovation of its building. The capital campaign for the project was seeded by a $160 million lead gift from Yale alumnus Edward P. Bass. In November 2021, the university announced that some of the funds amassed through the campaign would be used to fund free admission for the public in perpetuity.

Building Equity into Employment Practices

In 2017, Old Salem Museums & Gardens and The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts in Winston- Salem, North Carolina, began to fundamentally reshape their operations to reverse a decades-long slide towards insolvency. They began by expanding their leadership team to represent every division in the organization, making it more diverse in terms of race, gender, and economic status, and flattening the organizational chart to reduce the distance between senior and front-line staff. They produced a new balanced application and review process that reduces basic requirements for positions and values lived experiences as well as traditional educational attainments. All pay and job discussions now go through a collaborative senior leadership team, and Old Salem has launched an equity initiative that includes commitments to paying above a living wage for the area, implementing a cost-of-living raise for hourly staff, providing mental health benefits, and reducing the pay ratio of the CEO to lowest-paid exempt employees from seven-to-one to four-to-one.

New Metrics of Success

In 2022, the national Measurement of Museum Social Impact (MOMSI) project worked with thirty-eight museums to measure museum impact on health and wellbeing, valuing diverse communities, continued education and engagement, and strengthened relationships. This work built on a pilot project in 2017-2018 headed by the Utah Division of Arts & Museums in partnership with the nonprofit museum complex Thanksgiving Point for a statewide social impact study, collecting data from almost four hundred visitors through eight participating museums. The pilot evaluation showed that 96 percent of the 104 indicators tracked by the project showed a statistically significant positive change. The results from the national MOMSI project were released in 2023, along with a free toolkit with resources to help museums measure their social impact. As of June, 2024, with funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, AAM is recruiting a cohort of 30 museums to form the nucleus of a community of practice around metrics of social impact, test and refine the toolkit, compile data, and inform development of new resources museums can use in advocacy efforts.

Explore the Future

Signal of Change:

A “signal of change” is a recent news story, report, or event describing a local innovation or disruption that has the potential to grow in scope and scale. Use this signal to catalyze your thinking about how museums might help society create healthy and sustainable metrics of success.

The Seattle Times, November 15, 2021

In November 2021, Choose 180, a youth diversion nonprofit, raised all its staff salaries to a minimum of seventy thousand dollars a year. For some of the organization’s twenty-four staff, the pay hikes amounted to a twenty-thousand-dollar annual raise in an instant, using existing funds. (According to MIT’s Living Wage Calculator, a parent would need to make just shy of seventy-six thousand dollars to live in King County.) The increases added about four hundred thousand dollars to Choose 180’s 2022 budget, an amount the board supported unanimously. Executive Director Sean Goode said that when staff first suggested changing the pay structure, he initially balked. But one director reminded him that the philosophy of Choose 180 was that the living conditions of the young people they worked with needed to change in order for them to have a fighting chance to live beyond what he called “the disease of violence and the stress of poverty.” Could it be that they were paying their own team members to live in the same conditions? Goode said the conversation was a “gut punch” that sparked a transformation, and that he is confident he can fundraise to support the change going forward.

Explore the implications of this signal:

Ask yourself, what if paying a living wage became the norm for American nonprofits (perhaps even a metric of excellence valued by donors and funders)? Discuss three potential implications of this signal:

- For yourself, your family, or friends

- For your museum

- For the United States

Critical Questions for Museums

- What are the limits of traditional metrics of museum success such as growth in attendance, collections, and endowment?

- What metrics would foster more equitable and sustainable outcomes?

- How can museums contribute to healthy, equitable economies through the jobs they create?

- How can museums help their communities foster sustainable tourism?

- How can museums in shrinking cities “right-size” in a way that prioritizes equity and preserves heritage?

Framework for Action

Inward Action

To create systems that foster healthy, sustainable practice, museums can:

- Engage the governing authority and staff in a thoughtful exploration of what values the museum wants to embody in its work and what constitutes “success.”

- As part of this discussion, explicitly consider the “right size” for the museum in terms of optimizing benefits for the community, including both visitors and staff.

- Choose metrics that support these values and goals, and educate funders and donors about these measures.

- Create the capacity to collect the data needed to support these metrics, through staffing (in-house or contract), training, and integrating evaluation into program design.

- Examine the museum’s labor and compensation policies to ensure the museum is supporting the true costs of working for the organization.

Outward

To help their communities achieve the right size for success, museums can:

- As tourist destinations, help cities that are tackling “over-tourism” to craft strategies that benefit residents economically, preserve quality of life, and distribute tourism to underappreciated destinations.

- If located in communities that are shrinking due to economic and demographic forces, help create plans to manage that downsizing in a way that results in livable, right-sized communities, while preserving public heritage such as historic structures, districts, and public art.

Additional Resources

- Active Collections, edited by Elizabeth Wood, Rainey Tisdale, and Trevor Jones (2017). This collection of essays critically examines traditional approaches to museum collections, and explores new paradigms of stewardship, including “quality over quantity.” The corresponding Active Collections website (activecollections.org) shares “A Manifesto for Active History Museum Collections” (which states “we believe collections must either advance the mission or they must go”), case studies on right-sizing collections, and a section on crazy ideas, including the creation of a “deaccession special ops” team, and creating a “usefulness meter” for collections.

- Putting the Right In Right Sizing: A historic preservation case study (Michigan Historic Preservation Network, National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2021). This case study offers a number of observations for preservation and planning professionals about the role of preservation in cities undergoing right-sizing.

Excellent and thought-provoking … thank you.