How can museums build a healthy stream of charitable support?

“Philanthropy is an exercise of power. The question is not whether it is good or bad, but how we ensure it aligns with democratic values.”

— Robert Reich, American professor, author, lawyer, and political commentator

Peering into the future of philanthropy, we can see signs of hope and signals for concern for the museum sector. On one hand, the US is about to experience the greatest transfer of generational wealth in our nation’s history, with a significant portion expected to be directed toward charity. On the other hand, philanthropy is increasingly buoyed by a small segment of wealthy families. How will the increasing concentration of wealth, together with the values and goals of the next generation of donors, affect the nonprofit sector? Contributed income is more important than ever in the wake of profound disruptions to government funding. But does philanthropy have the capacity to fill that vast gap?

This article originally appeared in the Jan/Feb 2026 issue of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

» Read Museum.

Charitable foundations—a growing source of nonprofit support in recent decades—face their own challenges, including soaring demands for funding and increased government scrutiny of their work. For museums, the long-term work of cultivating community connections and small gifts may not pay off quickly enough to provide the safety net they need right now. How can museums cultivate charitable support to build a sustainable future, strengthen their accountability to the public, and stay true to their mission and values?

The Challenge

At first glance, the state of philanthropy in the US seems strong. Growth in giving from all sources has tracked the economy’s growth since 1992, hovering at around 2 percent of gross domestic product. Despite small downturns during the pandemic, we are experiencing the highest level of giving since the Great Recession of 2008. In 2024, the US recorded over $592 billion in charitable giving via individual gifts, bequests, foundations, and corporations. Eighty-three percent of this giving came from individuals (bequests and family foundations) and 4 percent—about $23.7 billion—went to arts, culture, and humanities organizations.

Looking forward, we are on the cusp of “The Great Wealth Transfer,” in which baby boomers will pass on close to $84 trillion, some of it to causes and institutions they believe in. Pundits estimate that $18 trillion may go to charity by 2048. If 4 percent giving to arts, culture, and humanities organizations holds true, that would result in over $720 billion flowing to such organizations, including museums.

That all sounds great. But the top-line numbers hide a troubling trend—fewer people are giving to charity, and younger donors are less likely to support arts and culture. The steepest drop in generational giving is among 51- to 60-year-olds, traditionally a demographically reliable set of donors, but giving across all generations has declined since 2008. The majority of Americans believe that young people are less likely to be better off than their parents, breaking the national narrative of upward progress. Members of the millennial generation (born 1981–1996) and Gen Z (born 1997–2012) face financial burdens that curtail their ability to give now and over the course of their financial lifetimes. Many carry significant student loan debt, and many launched their careers during financial crises (the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic) and may never recover from the damage to their entry-level salaries. They are less likely than their parents were at the same age to own a home or a car, and they have smaller savings.

Millennials and Gen Z individuals who do become donors bring different values and expectations to philanthropy. They see themselves as change agents, tend to support issues rather than specific organizations, and prefer to pair their financial support with volunteering. Their giving is strongly shaped by technology, influenced by social media, and often executed online. They engage in micro-giving through crowdfunding campaigns and online platforms, but even for donations as small as 25 cents or $25, they want to see demonstrable impact. And in prioritizing impact, they are more likely to support environmental and social justice issues and less likely than older donors to give to education or the arts.

If you are doing the mental math, you may be asking yourself how fewer donors and smaller gifts reconcile with robust charitable giving totals. The answer lies in the rising wealth inequality in the US. A growing portion of individual giving comes from a small group of well-off individuals. Households making over $1 million accounted for just 10 percent of charitable deductions in 1993, but that grew to 40 percent by 2019. Globally, donations from the ultrawealthy accounted for 38 percent of all individual giving in 2022—$94 billion in the US alone. And—good news for museums—arts and culture is the second most popular philanthropic cause among ultra-high-net-worth donors in the US.

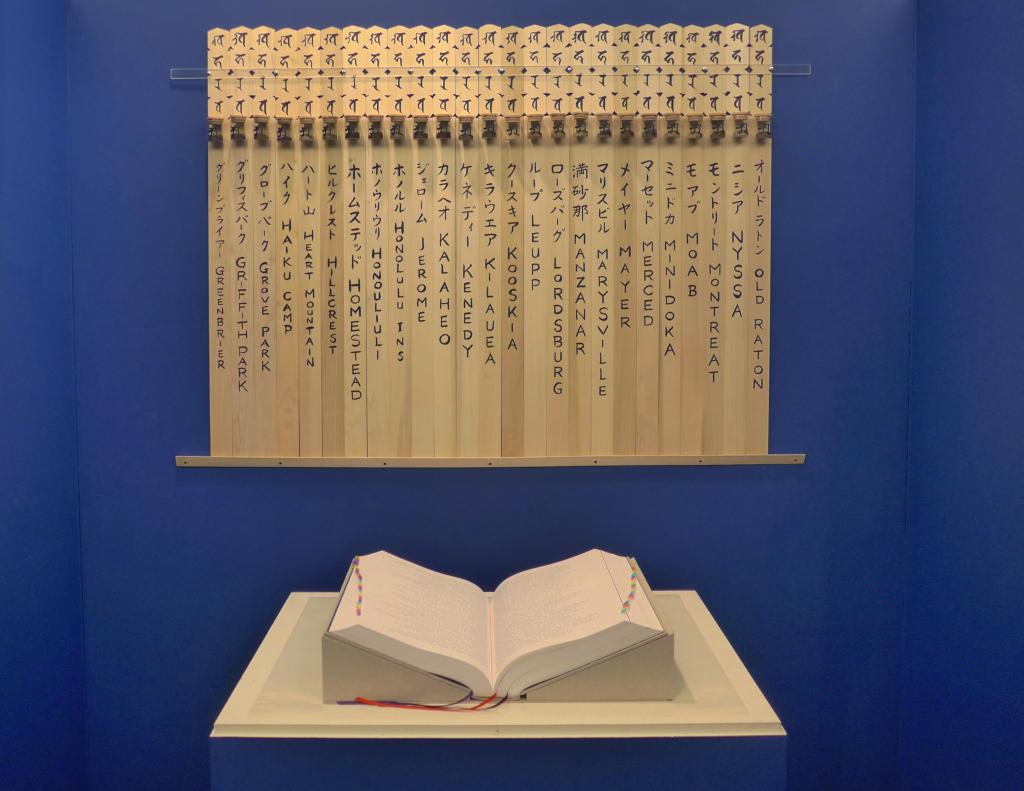

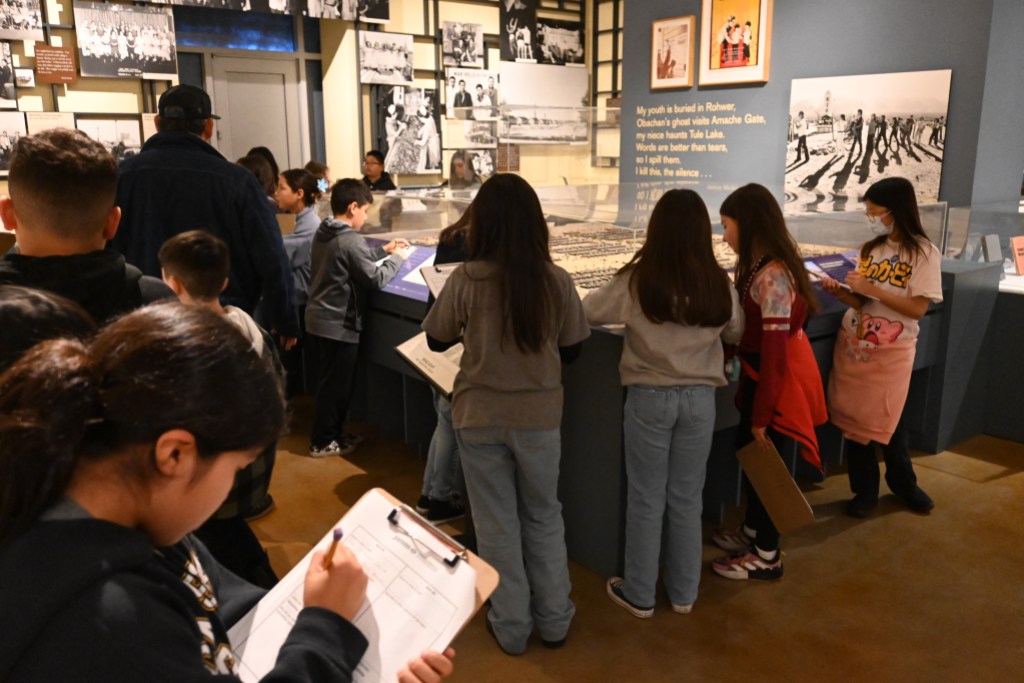

Ireichō book that contains the names of people incarcerated during World War II.

However, there is growing concern that the profound imbalance in wealth and philanthropy gives a small set of unelected individuals outsized influence over public sectors and public policy. (Though opinions vary on the net effect of this power—see the “Does Philanthropy Tilt Left, Right, or Center?” sidebar on p. 18.) Only 29 percent of Americans have high trust in wealthy individuals engaged in philanthropy, due in part to concern about disproportionate influence. Funding from a few ultra-high-net-worth donors has shaped US educational policy, driving or reinforcing an emphasis on testing, choice, competition, and charter schools that has not delivered its promised results. Some donors who have made their fortunes in tech focus on speculative futures like sending humanity into space, which does not address the immediate needs of real people. Some are bypassing philanthropy entirely, subscribing to venture capitalist Marc Andreessen’s “Techno-Optimist Manifesto,” which holds that the benefits to society from tech innovation are so valuable that technologists have no moral obligation to share the resulting wealth. Nonprofits serving more immediate needs in our communities might play a role in shaping the interests of these donors as their philanthropy matures.

While giving from the ultrawealthy may be considerable, it is falling far short of its potential and its promise. In 2010, Warren Buffett and Bill and Melinda Gates founded the Giving Pledge, challenging the world’s wealthiest to give away at least half their fortunes in their lifetimes or wills. Fifteen years on, of the 22 signatories who have died since 2010—including 14 of the original pledgers—just eight have fulfilled that promise. The majority of charitable gifts from all signatories have gone into private foundations, which are only required to pay out 4 percent of their value each year, or into donor advised funds (DAFs), which have no minimum payout. In 2023, DAFs held over $251 billion in wealth, increasing by 400 percent in the past decade. Growing bipartisan support for legislation mandating a significant payout rate for DAFs may activate more of these funds in coming years.

The growing concentration of wealth has also helped fuel the growth of charitable foundations, with almost 20 percent of ultra-high-net-worth individuals having created their own private foundations. In September 2025, the total assets of US charitable foundations stood at more than $1.6 trillion, and they account for 19 percent of charitable giving. Right now, many are looking to foundations, and their significant assets, as potential saviors for nonprofits reeling from government funding cuts. While foundations certainly can, and are, helping bridge the funding gap, they are unlikely to fill the chasm. According to Candid, private foundations would have to increase their grant-making by 282 percent to make up for the loss of federal grants, and that calculation doesn’t account for the loss of contracts and other government revenues. In addition, threats from the current administration, including pressure to align private grant-making with the president’s priorities and proposals to tax foundation endowments or remove their nonprofit status, have forced foundations to devote more of their resources to defending their independence.

While the current demand for increased funding is considerable, the most lasting impact of recent events may be changes in foundation practice, as the nonprofit funding crisis accelerates philanthropic reform. In the past decade, we’ve seen calls for foundations to stop treating their grantees’ operating expenses as waste (the Overhead Myth campaign) and to provide more unrestricted funding to good partners. (This movement is welcomed by the museum sector, which greatly lamented the end of the Institute for Museum and Library Services’ General Operating Support grant program in 2001.) At the time this is being written, over 186 grant-making organizations have signed on to the Trust-Based Philanthropy Project’s Meet the Moment Campaign, pledging to become better, collaborative partners; commit to multiyear funding; reduce paperwork; give unrestricted gifts and multiyear grants; and be flexible and responsive to the needs of grantees. Those changes, if they become embedded in foundation culture, could help ensure that the support foundations provide to the nonprofit sector is more equitable, stable, and appropriate.

What This Means for Museums

Where museums get their money shapes their behavior. (For a deeper dive into that thesis, read CFM’s 2020 TrendsWatch report on the Future of Financial Sustainability.) Broad-based support from many smaller donors makes a museum more accountable to that donor base (and to the extent those donors reflect the community, accountable to the community) but leaves it constantly striving to build a big enough base of support. Having one, or a few, major donors may free a museum to make aspirational choices but also entrains it to the donor’s goals, visions, and values, leaving the museum vulnerable to the loss of that major contributor. For medium-sized and small museums, the rising role of ultrawealthy donors is unlikely to offset the decline in giving by people with less financial capacity as these major donors tend to give to large, prominent museums or found their own institutions.

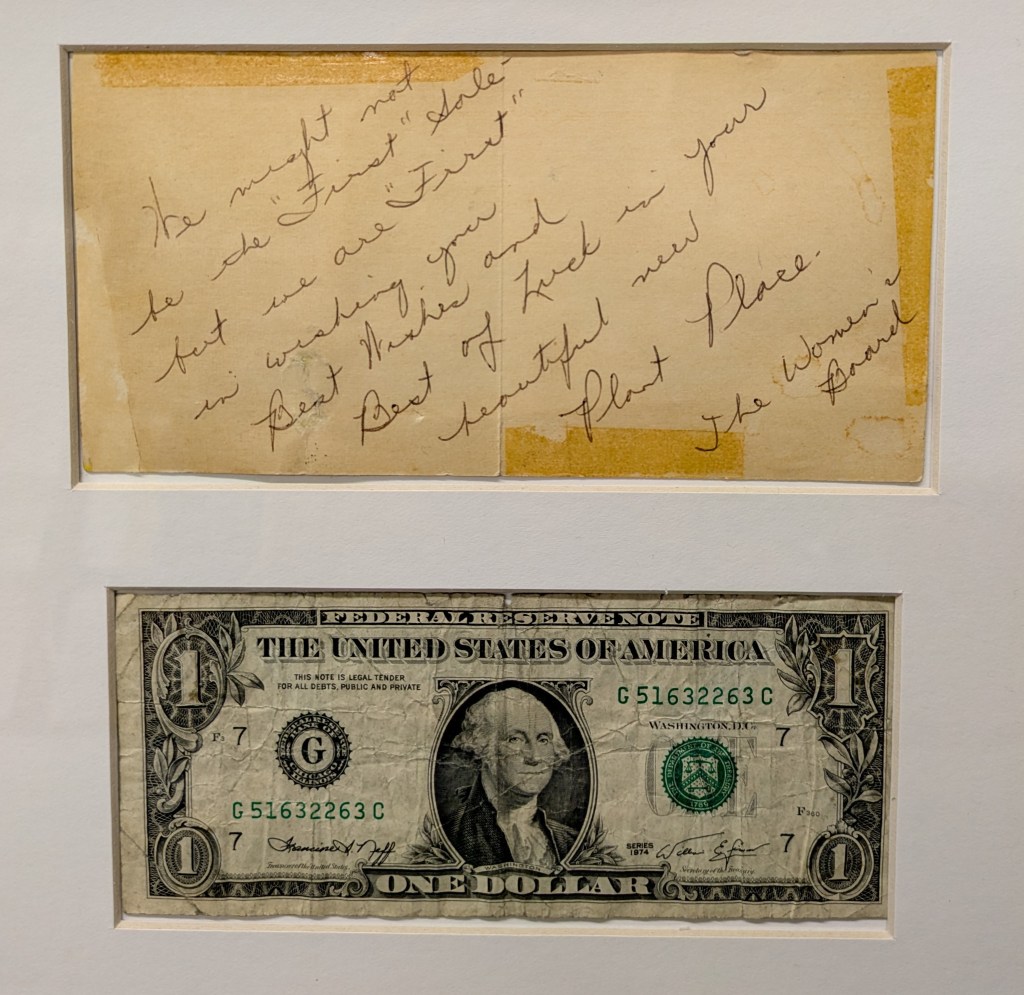

the hospital with the “first dollar” raised through its philanthropic efforts

The emerging trends in who can give, and what they are interested in supporting, compound long-standing challenges in what major donors are willing to fund. It has long been far easier to raise money for tangible naming opportunities—new buildings, additions, high-status staff positions—than to fund the underlying work. This bias toward building often creates long-term increases in operating costs not covered by the original gift. For some museums, one long-standing balance to this preference for naming opportunities is the expectation that members of the board of trustees make major, unrestricted gifts. This is great for cultivating general operating support but at odds with many museums’ growing desire to diversify their boards, making them more reflective of the communities they serve.

Cultivating major gifts shouldn’t displace asking “everyday people” to give. With Gen X, Y, and Z not accumulating wealth like previous generations, it’s imperative that museums build a broad base of support from donors of smaller amounts. Some generational shifts play to our sector’s strengths. Museums adept at social media can attract the support of followers from around the world. Volunteer opportunities offer younger donors the kind of engagement they want to pair with their giving. Museums with missions tied to issues such as environmental action or social justice can appeal to the cause-based passions of millennials and Gen Z.

With less federal funding and fewer major donors, museums may have to work differently so they can fundraise differently. In the early 2000s, the nonprofit arts field focused on diversifying audiences. The key to that success was creating new content—programs that appealed to diverse audiences—rather than just tweaking the marketing for legacy programs. Now museums need to tackle the same transformation with respect to fundraising. They can lay the groundwork for success by experimenting with innovative offerings and fundraising approaches that engage younger supporters.

Foundation funding has long played a large role in shaping the behavior of museums through the priorities they set for their grant programs. This can encourage museums to launch long-term, sustained work on an issue that is vulnerable to changes in foundation leadership and priorities. A current, unprecedented example is over a decade’s worth of museum diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) work that has been largely orphaned as many (though not all) foundations back away from programs being attacked by the current administration. This emphasizes the need for museums to build multiple, reinforcing layers of support for initiatives that arise from a museum’s own mission and values.

What’s Next?

Economic uncertainty caused by tariffs, disruptions to travel and tourism, and new tax policies will reshape philanthropy in the near future. Over the long term, these disruptions will be compounded by generational shifts in giving and growing wealth inequality. Wild cards include the potential for artificial intelligence to displace labor and increase financial precarity. And foundations may significantly increase or decrease their giving to arts and culture in the face of partisan pressure.

The takeaway for museums? Take nothing for granted. Fundraising practices that succeeded in the past will most likely need to change or expand to secure a broad base of stable support.

Museums Might …

- Devote resources to cultivating a reliable cadre of small-gift donors and engage in relationship building, not just fundraising. This creates a feedback loop of accountability that helps museums remain attuned to the needs of a bigger group of supporters; it is less vulnerable to sudden disruptions; and it comes with fewer strings attached.

- Cultivate the next generation of donors, particularly those who don’t represent traditional philanthropic sources (e.g., dynastic wealth or corporate leadership). Provide opportunities for donors to make a difference through their work with the museum in addition to their financial support.

- Experiment with emerging practices and technologies, such as micro-giving via crowdfunding, social media, and other digital platforms. While they may not yield large results in the short term, these experiments can prepare museums to succeed in an increasingly digital fundraising environment.

- Thoughtfully incentivize and reward fundraising. The way in which boards set goals for directors, or how directors establish expectations for development staff, profoundly affects the institution’s short- and long-term behavior. Accountability shaped around quick wins, single campaigns, and large, one-off gifts may discourage the long, hard, less flashy work of building a broad, reliable base.

- Create and strengthen firewalls that protect exhibit and program content from donor influence.

- Ensure that the museum’s priorities and needs of the people it serves drive fundraising, not the other way around. It is dangerously easy for large grants from foundations or individuals to shape a museum’s focus in a way that diverts it from its goals.

- Practice saying “no.” It can be hard to walk away from a major gift, but museums can lay the groundwork for thoughtful decision-making by creating a formal framework to ensure the right questions are asked about the gift and that potential issues are given due weight. Are there downside risks of a gift (diversion from priorities and/or values, long-term increase in operating costs, etc.)? What conditions on a gift are acceptable or unacceptable?

- Advocate with grant makers for healthy, sustainable funding practices, such as multiyear, unrestricted funding and simplified application and reporting processes. Take a firm stand against harmful practices, such as complicated, bespoke application forms, caps on overhead ratios, and onerous metrics.

- Advocate for increasing mandatory payouts from donor advised funds and undertake the research needed to access this funding.

Does Philanthropy Tilt Left, Right, or Center?

As I researched this article for TrendsWatch, I was disturbed by the extent to which philanthropy has become a partisan issue in the US. To adapt a phrase from the Museums are Not Neutral movement, “philanthropy is not neutral,” though opinions diverge on whether the collective impact leans left or right.

Wherever you stand on this issue, museums need to be aware that philanthropy is deeply entangled in current struggles over power, influence, and who we are as a nation. That being so, museums should consciously align their fundraising with their mission and values while understanding the practical, reputational, and (yes) political repercussions of philanthropic support.

To set the stage for such discussions, here is a brief summary reflecting the opinions of people who feel that philanthropy is predominantly driven by progressive or conservative values, or that it is, overall, a nonpartisan force for good.

Philanthropy Is Driving a Partisan Agenda

Philanthropy in America reflects a liberal right-wing bias and concentrates too much influence in the hands of progressive conservative donors and foundations. Many of the largest philanthropic institutions—such as the Ford Foundation, Open Society Foundations, and the Gates Foundation—support causes that align with liberal or progressive values, including climate action, racial equity, immigration reform, and expanded social programs. Wealthy individuals and families—such as the Kochs, the Bradley Foundation, and the DeVos family—have poured billions into conservative institutions like The Heritage Foundation, American Enterprise Institute, and the Federalist Society that have created the intellectual and legal framework behind key conservative priorities, from weakening environmental regulations to restricting voting access and limiting reproductive rights. This distorts the democratic process by amplifying progressive conservative viewpoints while marginalizing dissenting perspectives. As a result, modern philanthropy risks becoming a form of ideological power—used not just to help society but to steer it in a direction favored by a wealthy, left- right-leaning elite.

Philanthropy Is a Shared Force for Good

Philanthropy in America provides a mechanism for individuals, families, and organizations to invest in the public good. American philanthropy is uniquely robust, driven by a culture that encourages charitable giving and fosters a sense of shared responsibility and purpose. Moreover, philanthropy strengthens democracy by supporting an active civil society, funding institutions that educate, advocate, and serve, often amplifying voices that might otherwise go unheard. Importantly, it transcends partisanship—Americans of all political backgrounds engage in charitable giving.

Museum examples

The Toledo Museum of Art (TMA) has designated approximately $2.5 million in planned gifts to establish a long-term source of funding for staff professional development. TMA incorporated the anticipated yield from the endowment into its annual operating budget, ensuring stable, recurring support for learning and growth across all departments. This approach reflects TMA’s conviction that investing in people is as vital as investing in collections or capital. TMA now allocates professional development resources at a level believed to be among the highest per full-time employee in the art museum field (approximately 2 percent of its operating budget). New initiatives include the launch of a management development program, coaching for high-potential employees outside of the leadership team, and an expanded travel budget. By aligning philanthropic intent with operational practice, TMA models how planned giving can advance workforce development and sustain institutional vitality well into the future.

In June 2025, the National WWII Museum in New Orleans announced a $300 million Victory’s Promise fundraising campaign. As the World War II generation passes on and direct connections to the war fade, the museum faces the challenge of engaging a wider audience and cultivating a new generation of supporters. The campaign will enable the museum to expand its programming on its campus as well as across the country and online, with a goal of educating 5 million K–12 students and 15,000 teachers annually by 2035. The campaign will also strengthen the teaching and study of WW II history through increased support and mentorship of higher education faculty, scholars, and students, and the creation of the new Sanderson Leadership Center that will promote strategic thinking and key leadership principles to new generations of American leaders.

The Japanese American National Museum (JANM) folds digital approaches into its fundraising toolkit. In 2025, this included the #ScrubNothing social media appeal that helped more than replace cancelled National Endowment for the Humanities funding and an online auction that helped its annual benefit raise over $1.2 million to support the museum’s mission and educational programs. In January 2025, JANM launched a crowdfunding campaign for the national tour of Ireichō, a sacred book containing the names of people of Japanese ancestry who were unjustly incarcerated in the US during World War II. The seven-week digital campaign raised $125,284—one dollar honoring each name inscribed in the book—and ended on the Day of Remembrance, commemorating the signing of Executive Order 9066, which ordered the incarceration. This campaign exemplifies how JANM uses fundraising to uphold its principles, engage audiences with its mission, and inspire the next generation to give.

Resources

Museum Philanthropy & Fundraising Tipsheet, American Alliance of Museums, 2024

This tipsheet summarizes the insights from museum development leaders Charles Katzenmeyer, Eowyn Bates, Amy Burt, Shannon Joern, and Ginevra Ranney. (AAM Member resource)

aam-us.org/2024/04/12/museum-philanthropy-fundraising-tipsheet

Planning for Sustainable Success: Fundraising Management in a Changing World, recorded session from the 2020 AAM Virtual Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo

Presenters Donna McGinnis, President & CEO, Naples Botanical Garden, and Kate Brueggemann, VP, Development, Adler Planetarium, discuss how their organizations navigated the uncertainties of fundraising during the COVID-19 pandemic. (AAM Member resource)

aam-us.org/2021/12/16/planning-for-sustainable-success-fundraising-management-in-a-changing-world/

Meet the Moment: A Call to Action for Philanthropy Now & Into the Future, Trust-Based Philanthropy

Project, 2025

This site outlines steps many foundations are taking to provide flexible, appropriate support to nonprofits in a time of crisis and lists the funding organizations that have signed the commitment.

trustbasedphilanthropy.org/meet-the-moment