This article first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Spring 2025) Vol. 44 No. 1 and is reproduced with permission.

Contemporary art exhibitions have long been considered places where political ideas can be explored, a space arguably of multiple perspectives, where different possibilities can be offered.[1] As a result, it is commonplace to see exhibitions within certain contemporary institutions about protest, unrest, and all manner of social movements, particularly those relating to liberal, left-leaning politics. These ideas are shown through the artworks on display, where artists are engaging directly with political ideas, and through the framing of the exhibition and language used. For artists, curators, and many others working in art institutions, the relationship to these subjects is not new or unusual, as politics have historically been central to and well represented within artistic practices. The decisions made by both artists and curators to work with political subjects are of an ethical nature: they make judgments on what they believe to be just, and the work becomes embedded with these ideas. The nature of exhibitions then places these ethics in the public realm so that they can be viewed by a wider audience, including by visitors who may not agree or espouse such politics themselves.

While politically engaged exhibitions have become a cultural mainstay of the 21st century, as time goes on, the institutions that choose to present these subjects have increasingly found their own politics critiqued by a wide range of observers. Greater scrutiny is being placed on these institutions, with arguments being made that the forward-facing politics they present are in opposition to the politics they practice within their organizations, for example, through funding choices and labor practices. Given that our art institutions are representatives of the wider societies they inhabit and the political systems that govern them, to many there is at best a disconnect between the exhibitions they present and the stories being told in society writ large and, at worst, an unethical case of co-option whereby progressive politics are flattened and reduced to nothing more than style when placed in these spaces. This has resulted in an increasing number of public calls for change, with boycotts, open campaigns, and withdrawals of labor being used to highlight these issues. This article will look at a recent wave of these instances in the United Kingdom and consider how art institutions could program politically engaged exhibitions in ways that do not compromise the ethics of the artists—and oftentimes the curators and staff—involved.

Institutional Critique in the Current Context

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, museums and art institutions have faced a period of reckoning. While their doors were closed during the lengthy lockdowns, we saw a rise in institutions looking inward, taking time to examine their practices and question what they were doing and for whom. The murder of George Floyd in May 2020 led to the growing public consciousness of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement—already established in the U.S. in 2013 and in the UK in 2016—and to a wave of related protests that spread from the U.S. to Europe. In the UK, this was compounded when data, published in the summer of 2020, showed the disproportionately high COVID-19 death rates for Black communities and populations from the Global Majority, bringing broader issues of inequality into focus.[2] Demonstrations and public outcry accelerated introspection as museums, like many industries, found themselves called to take accountability for their racist pasts and current practices. Art institutions were called to stand in support of Black communities and against racism, and, while many published statements that did this, anything seen as simply performative was no longer enough.[3] Art institutions were asked to examine their origins, collections, programming, and governance and to make fundamental changes to become spaces of demonstrable equity.

This moment can arguably be understood as a third wave of institutional critique. The first wave, in the late 1960s, was an artistic practice. The second wave, in the 1990s, accompanied the rise of relational aesthetics, which claimed that art was inextricable from the human relations and social contexts within which artists were operating.[4] This newest wave comes from, through, and outside institutions and is focused on a need for institutional change that is situated within a broader political struggle linked to resisting a global rightward shift. For many art institutions this has posed a dilemma: they are being called publicly to make their political intentions clear (something that, previously, institutions have not needed to engage with), while still claiming the need for impartiality and neutrality, their standard “ethical” stance. Much has been written telling us that this is an impossibility, even if an easy option for those in leadership roles in art institutions. We can further learn from the #museumsarenotneutral campaign how these assertions gloss over the colonial history of museums’ very creation.[5]

By using exhibitions as a space for politics, institutions have effectively been able to remove themselves from these conversations: they can showcase an idea or viewpoint without claiming that it is necessarily their own. Until recently, this approach has not been so widely challenged and has arguably satisfied both the audiences who agree with the artists’ and curators’ ideas and more conservative governing structures. These structures are those entities, individuals, and foundations that, in many cases, fund these institutions and exhibitions. That funding can often be conditional, as the following case study reveals.

The Barbican Unravels

Alongside more intense critiques of their standpoint of neutrality, the arts have also been moving into an increasingly hostile environment. Funding has become more competitive, and, as a result, we see institutions becoming more reluctant to take an overt political stance. In February 2024, the Arts Council England, the predominant funder of artists and arts venues in England, revised its guidelines to include advice on the “reputational risk” “political statements” could have for artists and that could put their funding under threat.[6] Artists’ reactions were swift and overwhelmingly negative: they claimed the guidance was akin to censorship and would silence more politically engaged artists. Artists speaking out about the violence in Gaza were particularly enraged, as the timing of the changes seemed designed to target them. Their concerns were confirmed in May, when a report revealed that the guidance had been written following a conversation between the council and the government about Israel’s war in Gaza.[7]

Concurrently, in February 2024, the Barbican Centre in London opened Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, a landmark group exhibition of over 50 artists who have used textiles as a medium of “power, resistance and survival.”[8] The exhibition was co-curated with the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, where it toured later in 2024. The exhibition featured artists from around the globe, with works dating from the 1960s to the present day (fig. 1). Unravel was carefully researched and respectful of the materials shown, the artists’ intentions when making them, and of textiles as a medium more broadly. The curatorial team, led by Lotte Johnson and Wells Fray-Smith of the Barbican Centre and Amanda Pinatih of the Stedelijk Museum, worked with scholar Julia Bryan-Wilson as an advisor on the catalogue, using her celebrated (and overtly political) Fray: Art and Textile Politics as a key and foundational text.[9] The exhibition sought to highlight the history of textiles as a medium that has great political potential, recognizing that the curators are not uncovering new claims or materials but situating them together across an exhibition that was to take place in two of Europe’s most established institutions. In the foreword of the catalogue, Shanay Jhaveri (Head of Visual Arts at the Barbican) and Rein Wolfs (Director of the Stedelijk Museum) cite wider politics as being important inspiration for building the exhibition:

“The conceptual origins of and research for this project began in 2020 at a moment when the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement and ongoing environmental destruction and mass extinctions were being felt acutely in both London and Amsterdam, where the Barbican Centre and Stedelijk Museum are located. Institutions and their structures were called into question; the distribution of power was examined and protested.”[10]

They are speaking directly to the aforementioned moment of reckoning for museums, where institutional critique moved from conversation and theory to direct calls for change. It is plausible to see Unravel as a response to these calls and to understand the display of these artworks of politics, resistance, and protest as a means of demonstrating change and engagement—as a potential move away from the ethics of neutrality.

Then, just days before Unravel opened on February 13, 2024, the Barbican was in the press for a completely different political statement: its decision not to host a London Review of Books (LRB) lecture series because it was due to include a talk that would make reference to the ongoing genocide[11] in Gaza.[12] In a statement, LRB claimed that the venue had been confirmed to host the talk by author Pankaj Mishra until its title, “The Shoah after Gaza,” was publicly advertised.[13] In a corresponding statement, the Barbican claimed this was not the case and that it had been prematurely announced as the venue before a decision had been made.[14] The statement went on to claim that the institution’s decision to not host the event came from a place of care:

“As we continue to undergo deep organisational cultural change, we know we have a particular responsibility to ensure that when we provide a platform for important and complex subject matter like this, we do so especially sensitively. On this occasion we didn’t feel we would be able to guarantee this given the circumstances, which is why we agreed with the LRB that the events would be hosted at an alternative venue.”[15]

The Barbican’s statement was meant to refute claims that this was an act of censorship or silencing, but this was contested widely—across the press, the internet, and in wider discussions.[16] The institution’s decision was not viewed singularly but in connection to other widespread instances of museums and galleries canceling or withdrawing support from events and artists speaking directly to the situation in Palestine across the UK, Europe, and globally.

Fallout

While the LRB event was not part of the exhibition program and would have had no overt link with Unravel, in the weeks that followed the two were discussed together and the exhibition was fundamentally impacted, arguably bearing the brunt of leadership’s decision. On February 29, 2024, two quilts by Loretta Pettway, one of the Gee’s Bend quiltmakers, were removed from display at the request of the collectors who had loaned them, in direct response to the decision to cancel Mishra’s lecture.[17] Pettway’s quilts had been exhibited in the section of the exhibition “Fabric of Everyday Life,” which framed textiles as an integral part of our lives, interwoven with memory and history.[18] The exhibition label that further contextualized these works read, “Embedded in these two quilts are stories of love, resilience and survival” further framing them as linked to the marginalization Pettway and the wider Gee’s Bend collective experienced.[19]

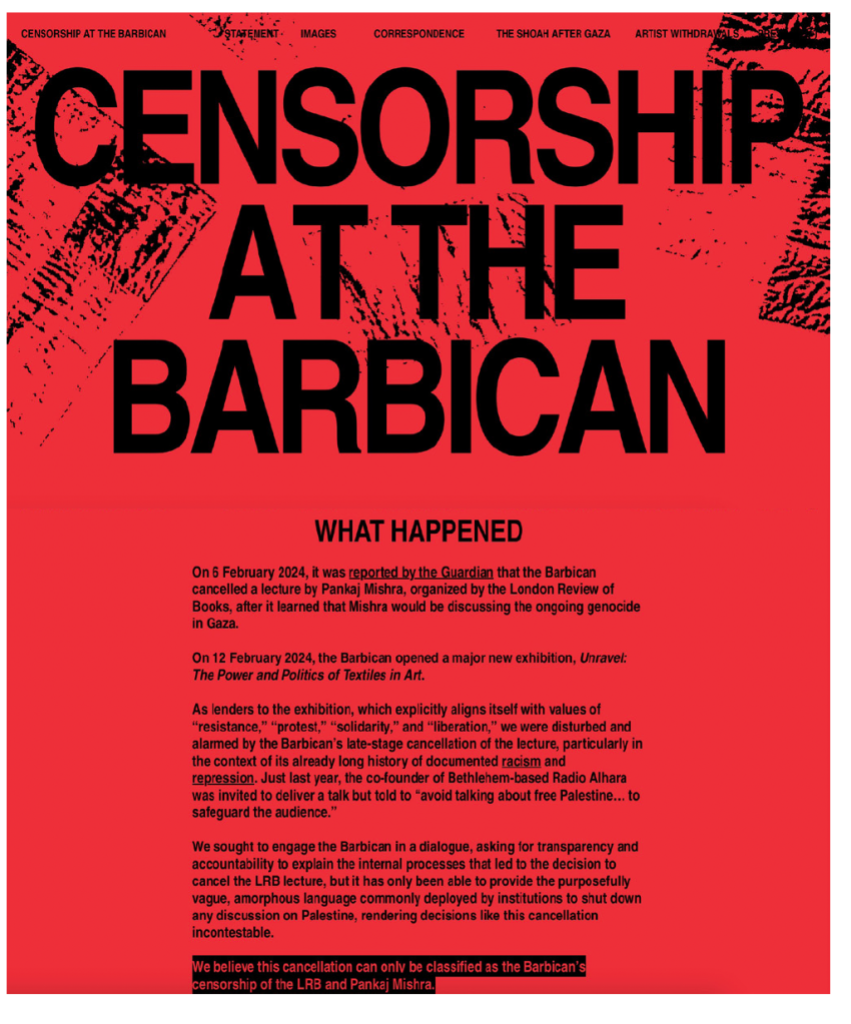

The collectors of the quilts, Lorenzo Legarda Leviste and Fahad Mayet, have since made their correspondence with the Barbican public, and the full event is documented on the website, Censorship at the Barbican (fig. 2).[20] The correspondence reveals that Leviste and Mayet’s decision to request the removal of their loaned works did not happen immediately but after a back and forth with members of staff at the Barbican. The first email, authored only by Leviste, begins by asserting support of the exhibition:

“I am moved by the project’s deep commitment to the political and conceptual capacities of textile as a medium, which in itself is a political gesture, as well as a curatorial position. It’s an assertion that’s intellectually provocative and exciting on paper, but in person I found emotional, raw, sumptuous, painful, of course beautiful. It’s an overwhelming show in the best way.”[21]

This statement further highlights the political position that was clear within the exhibition, a position the collectors believe is at odds with the decision to pull support for the LRB lecture series. They clearly link the resistance and support of marginalized people that are integral parts of Pettway’s practice—alongside broader instances of resistance documented through the exhibition—to contemporary acts of resistance that this event would have supported.

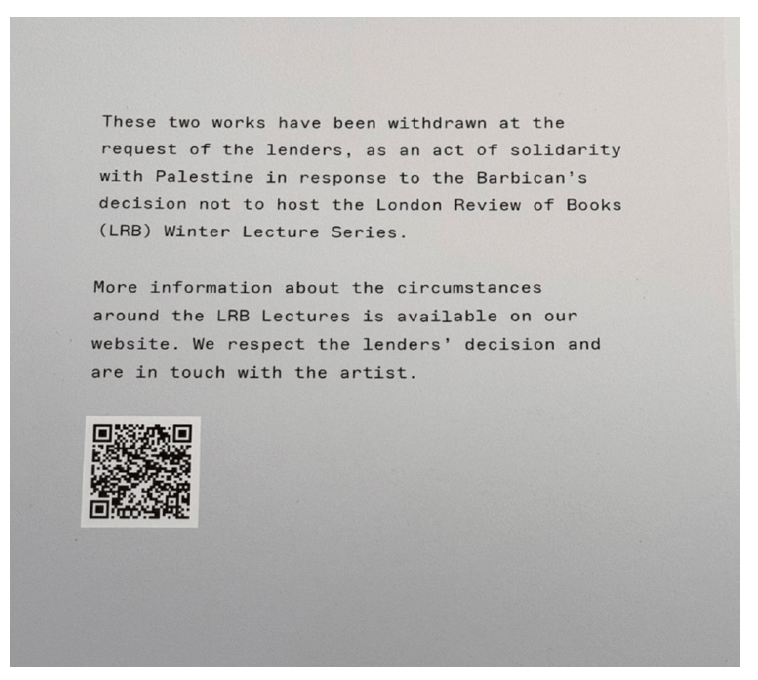

The correspondence reveals how Leviste and Mayet came to their decision to have the works removed from Unravel, ultimately concluding that the reasoning they were being given for the cancellation of the event was unsatisfactory. They cite “vague,” “unoriginal,” and “gloopy” language that ultimately gives no clarity or transparency to the matter and how the decision was reached.[22] After the works were removed, the collectors made a public statement in which they asserted their belief that the Barbican had acted to repress and silence Palestinian voices, an act of racism and institutional violence that was not in the spirit of the works they have collected and the reasoning they had for loaning them to the exhibition.[23] In the following weeks, nine more artists and collectors withdrew their works from Unravel, releasing additional statements that the Barbican’s cancellation of the LRB lecture was not aligned with their works and the exhibition more broadly.[24] Signage replaced the withdrawn works, reading:

“[the works] have been withdrawn at the request of the lenders, as an act of solidarity with Palestine in response to the Barbican’s decision not to host the London Review of Books (LRB) Winter Lecture Series.

More information about the circumstances around the LRB Lectures is available on our website. We respect the lenders’ decision and are in touch with the artist.”[25]

The gaps and accompanying statements remained for the duration of the show (fig. 3). Other artists chose to have their works remain but requested that statements or interventions be included alongside them, all in solidarity with Palestine.

Most statements, including the first by Leviste and Mayet, highlighted that this was not the first time the Barbican had been criticized for its handling (or lack) of discussion relating to Palestine. In June 2023 the institution issued an apology after a member of staff sent a text message to Elias Anastas, cofounder of the Palestine-based Radio Alhara, asking him to, “In terms of content, avoid talking about free Palestine at length…just to further safeguard the audience,”[26] shortly before he spoke remotely at an event at the institution.[27] The institution’s response in that case was more apologetic, stating that this “editorial note” had been “unacceptable and a serious error of judgement.”[28] Prior to this, in June 2021, an extensive whistleblowing report was published by current and former staff of the institution that recorded their experiences of racism while working at the Barbican. The report runs well over 200 pages and includes roughly 100 individual accounts of racism and discrimination alongside a timeline mapping events at the institution since the murder of George Floyd.[29] The report’s authors criticize the Barbican’s attempts to pay lip service to institutional racism without doing anything to address and change its own practices and prejudices. All these episodes received considerable public attention, with the Barbican in many ways being held up as a case study for ethical failings that occur across our art institutions.

Calls to Action Beyond the Barbican

The Barbican Centre is by no means the only art institution to be criticized in this way; there are many similar instances of repression and subsequent challenges throughout the UK, Europe, and the U.S., which demonstrate that this is a pervasive and urgent issue of discussion among those working with, in, and otherwise supporting art institutions. In December 2024, as I (the author) was first drafting this article, Scottish artist Jasleen Kaur was announced as the winner of the 40th iteration of the Turner Prize at an award ceremony at Tate Britain, London. Outside the ceremony was a protest made up of artists, cultural workers, students, and others who supported an open letter that had been sent to Tate the previous week demanding that the institution sever ties with its Israel-complicit donors and sponsors.[30] In her speech, Kaur spoke in favor of the protestors, committed to standing with them, and reiterated their call for Tate to divest.[31] Two weeks earlier, photographer Nan Goldin had delivered a similarly powerful speech at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin at the opening of her retrospective This Will Not End Well. This event was also attended by pro-Palestinian protestors, who spoke of the many instances of silencing of any discussion of Palestine in cultural venues across Germany that had occurred since October 2023.[32]

These artists and activists, like the collectors and artists who removed their work from Unravel, are committing to their own ethics. As Kaur stated in her speech, “I’ve been wondering why artists are required to dream up liberation in the gallery, but when that dream means life, we are shut down…. I want the institution to understand: if you want us inside, you need to listen to us outside.”[33] These ethical stances are not separate from an artist’s work but part of it; politics are practice.

Art institutions are representing these ethics when they exhibit these artists’ works and when they conceive exhibitions that are political in their intent. In a page on the Barbican’s website, the institution outlines its political position in these terms:

“Artists play a crucial role in reflecting, commenting on and responding to the issues of the day, including subjects that are urgent, complex or divisive. Cultural institutions such as the Barbican have a responsibility to provide artists – particularly those who may have been marginalised – with a platform to do so.

Our programming therefore often deals with political and social topics, and we aim to host the broadest and most diverse range of artists and thinkers, representing the widest possible range of world views and human experiences. To enable this, and also because we are a publicly funded arts organisation, all of our actions and statements are grounded in our purpose, values and programme. Although we may all have individual views, as an organisation we do not campaign on global or party-political issues.”[34]

This position shows that currently there is no move toward recognizing the increasingly loud and urgent calls coming from artists like Kaur. It seems clear that as long as art institutions continue to insist upon neutrality as the basis of their ethics, exhibitions—and programs, artist talks, and other events—that do represent a political standpoint will continue to be up for debate, and this oppositional standpoint will continue. Neutrality cannot support resistance and, at some point, museums and institutions will need to decide what their ethics means to their organizations.

The situation at the Barbican also makes clear that it is left-leaning politics that tend to get censured by institutions as violating their call to neutrality, while center and center-right politics are allowed to pass as “neutral.” While this could simply be because there are more instances of left-leaning politics challenging the institution, it also is apparent that these normalizing actions further enable a society-wide rightward drift. The politics and ethics (or lack thereof) of such supposed acts of neutrality become all the more insidious when there are finances attached to them.

Arguably, by choosing to program politically engaged exhibitions, institutions like the Barbican are aligning themselves with them. Artists and engaged members of the public take issue when these same institutions do not further commit to this standpoint or allow it to flow through the rest of their practices. Of course, there is a difference between individual views and institutional views, but an exhibition is a representation of the institution.

To return to Kaur’s speech, there is no difference between the world presented in an exhibition and the world we live in, which is also the world that the institution exists in. It is clear that institutional resistance to committing publicly to a political standpoint, even if one seems evident through their programming, comes in part through fear of alienating existing or potential funders and other sources of stability. This gives those who hold the purse strings, whatever their individual ethics may be, increasing power over what institutions are—and are not—willing to do. But what is to keep institutions, artists, and the exhibitions they create from challenging this world? Rather than bending politics to suit funders, is there no potential to admit that the current system is broken and that alternatives need to be found? Funders may turn down institutions, but what if institutions started exercising their right to turn down funders?

Recently, Nottingham Contemporary, a mid-size contemporary art institution in the UK midlands built on a traditional institutional structure, did make an institutional challenge to expected behavior. In February 2025, the institution publicly defended its work with the group Palestine Solidarity Campaign (PSC).[35] Nottingham Contemporary had previously held several events in collaboration with PSC, including a day-long festival that raised funds for the campaign and celebrated different aspects of Palestinian culture including food, music, and dance.[36] These activities were criticized by a whistleblower group that reported concerns to the Charity Commission, believing the institution may be acting in breach of its status through this ongoing relationship. To date, Nottingham Contemporary has stood by its partnership with PSC, stating that any collaborations with PSC are made in line with its ethos and aims as an organization.

This is but one example of the choices institutions are making to stand by their politically engaged programming, even when doing so risks their funding—in this case through the investigation being undertaken by the Charity Commission. So, while it may be difficult to rethink something that has previously seemed so fundamental, we can and must learn that ethics do not need to be—and should not be allowed to be—compromised and instead begin to dream up our own liberation.

Nicola Guy, PhD, is a Lecturer in Arts Administration and Cultural Policy at Goldsmiths, University of London.

[1] Philipp Dietachmair and Pascal Gielen, The Art of Civil Action: Political Space and Cultural Dissent (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2017), 18.

[2] Jennie Gamlin, Sahra Gibbon, and Melania Calestani, “The Biopolitics of COVID-19 in the UK: Racism, Nationalism and the Afterlife of Colonialism,” in Viral Loads: Anthropologies of Urgency in the Time of COVID-19, ed. Lenore Manderson, Nancy J. Burke, and Ayo Wahlberg, (London: UCL Press, 2021),108–27.

[3] Geraldine Kendall Adams, “Beyond the Black Square: Slow Progress on Sector’s Anti-Racist Commitments – Museums Association,” Museums Association, June 18, 2021, https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/2021/06/beyond-the-black-square-slow-progress-on-sectors-anti-racist-commitments/.

[4] Gerald Raunig and Gene Ray, Art and Contemporary Critical Practice: Reinventing Institutional Critique (London: Mayfly, 2009).

[5] La Tanya S. Autry and Mike Murawski, “Museums Are Not Neutral: We Are Stronger Together,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.2277.

[6] Kendall Adam, “Arts Council to Clarify Guidance after NPO Censorship Row,” Museums Journal, Museums Association, February 15, 2024, https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/2024/02/arts-council-responds-to-npo-censorship-row/.

[7] Simon Childs, “Arts Council Warning against Political Statements Came after Government Talks on Gaza,” Novara Media, May 24, 2024, https://novaramedia.com/2024/05/20/arts-council-warning-against-political-statements-came-after-government-talks-on-gaza/.

[8] Lotte Johnson, Amanda Pinatih, and Wells Fray-Smith, eds., Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art (London: Prestel, 2024), 7.

[9] Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art and Textile Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

[10] Johnson, Pinatih, and Fray-Smith, eds., Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, 7.

[11] “Amnesty International Concludes Israel Is Committing Genocide against Palestinians in Gaza,” Amnesty International, December 5, 2024, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/12/amnesty-international-concludes-israel-is-committing-genocide-against-palestinians-in-gaza/.

[12] Lanre Bakare, “Barbican Backs Away from Hosting Talk about Gaza War,” The Guardian, February 6, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2024/feb/06/barbican-backs-away-from-hosting-talk-on-alleged-israeli-genocide-in-gaza.

[13] Ibid.

[14] “A Statement from the Barbican in Relation to the London Review of Books Winter Series,” Press Room, Barbican, March 8, 2024, https://www.barbican.org.uk/our-story/press-room/a-statement-from-the-barbican-in-relation-to-the-london-review-of-books-winter.

[15] Ibid.

[16] See, for example, Oscar Rickett, “Barbican’s Cancellation of LRB Talk Exposes ‘Huge Rift’ over Israel-Gaza,” Middle East Eye, February 7, 2024, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/israel-palestine-barbican-talk-arts-censorship; Lara Olszowska, “Barbican under Fire for Censorship, Leaked Emails Reveal,” Evening Standard, March 7, 2024, https://www.standard.co.uk/news/londoners-diary/barbican-under-fire-for-censorship-leaked-emails-reveal-b1143720.html; and Lanre Bakare, “Barbican Backs Away from Hosting Talk about Gaza War,” The Guardian, February 6, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2024/feb/06/barbican-backs-away-from-hosting-talk-on-alleged-israeli-genocide-in-gaza.

[17] Jo Lawson-Tancred, “Collectors Withdraw Loaned Works from London’s Barbican in Solidarity with Palestine,” Artnet News,” March 6, 2024, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/collectors-withdraw-loaned-works-from-londons-barbican-in-solidarity-with-palestine-2447438.

[18] Johnson, Pinatih, and Fray-Smith, eds., Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, 77.

[19] Barbican, “Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art Large Print Guide,” September 2, 2024, 18.

[20] Lorenzo Legarda Leviste and Fahad Mayet, “Statement,” Censorship at the Barbican, accessed January 6, 2025, https://censorshipatthebarbican.com/#statement.

[21] “Correspondence,” Censorship at the Barbican, accessed January 6, 2025, https://censorshipatthebarbican.com/#correspondence.

[22] Ibid.

[23] “Statement,” Censorship at the Barbican.

[24] “Artist Withdrawals,” Censorship at the Barbican, accessed January 6, 2025, https://censorshipatthebarbican.com/#artist-withdrawals-1.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Rivkah Brown, “Barbican Forced to Apologise for Silencing Palestinians,” Novara Media, June 20, 2023, https://novaramedia.com/2023/06/20/barbican-forced-to-apologise-for-silencing-palestinians/.

[27] Technical difficulties on the side of Barbican eventually stopped Anastas from contributing to the event at all.

[28] “A Statement from the Barbican,” Press Room, Barbican, accessed December 8, 2024, https://www.barbican.org.uk/our-story/press-room/a-statement-from-the-barbican-0.

[29] “Barbican Stories – Everything You Need to Know about the Barbican an Indispensable Record of Discrimination in the Workplace,” Barbican Stories, June 10, 2021, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/60aa3e5fd20de56185608cf1/t/640644ec5352385310c092d8/1678132832015/BarbicanStories_June2021.

[30] “Tate: End Your Complicity in Genocide,” Google Forms, November 25, 2024, https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSfIOnET354J_vV883HDqWlkJOPi5FkEhuiwmyW80saGw5bBWA/viewform.

[31] Nadia Khomami, “Jasleen Kaur Wins the Turner Prize 2024,” The Guardian, December 3, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2024/dec/03/jasleen-kaur-38-wins-the-turner-prize-2024.

[32] James Grieg, “Nan Goldin Makes Powerful Speech Condemning Gaza ‘Genocide,’” Dazed, December 9, 2024, https://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/65325/1/nan-goldin-makes-powerful-speech-condemning-genocide-in-gaza-palestine-israel.

[33] Nadia Khomami, “Jasleen Kaur Wins the Turner Prize 2024.”

[34] “Our Political Position,” About Us: Purpose and Governance, Barbican Centre, accessed February 18, 2025, https://www.barbican.org.uk/our-story/about-us/purpose-and-governance.

[36] Oliver Pridmore, “Nottingham Contemporary defends work with Palestine group after regulator looks into concerns,” Nottinghamshire Live, February 25, 2025, https://www.nottinghampost.com/news/nottingham-news/nottingham-contemporary-defends-work-palestine-9972575.

[37] “PSC Palestinian Cultural Day,” Nottingham Contemporary, accessed March 7, 2025, https://www.nottinghamcontemporary.org/whats-on/psc-palestinian-cultural-day/.