Museums strive to be permanent institutions that make cultural objects accessible for the benefit of society. Does this mission imply that museum collections must also be permanent, or can objects be transient? When is it acceptable to remove objects from museum ownership? And who decides?

This Point of View originally appeared in the Sept/Oct 2025 issue of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

» Read Museum.

Many museum practitioners in the UK are grappling with these important questions as they face overfilled collection storage facilities, shortfalls in core funding, and reduced visitorship—and therefore income—since the pandemic. Amid these pressures, there is a noticeable, and seemingly growing, interest in the UK to sell objects from collections to fund financial shortfalls. Indeed, one international auction house recently contacted UK local government councils offering to value historic items.

Yet the UK museum sector remains adamant that financially motivated disposal is unethical as it breaches public trust and prioritizes an object’s economic worth over its cultural and social significance. Selling one’s way out of crisis is not the answer. Instead, many museums are acknowledging collections as active, evolving entities that need to be shaped ethically and responsibly.

With strong ethical guidance from the Museums Association (the UK equivalent of AAM), UK museums are accepting that past decisions do not need to restrict their practices today. Museums can become more sustainable by carefully reviewing their collections and removing objects that lack provenance, are under-used or duplicative, fall outside the mission, or are in poor condition. These decisions must be made with deep ethical consideration about the history and future use of individual objects, and the diverse ideas and needs of varied audiences.

Acting Inclusively and Transparently

As museum professionals, we live in what I call a “temporal quandary.” We are rooted in the present but constantly looking backward—honoring legacy decisions—while trying to anticipate future needs and values. That raises thorny questions: Who are we to undo the decisions and actions of our predecessors? How can we predict what future audiences will want or need?

The simple answer is: we can’t. What we can do is make thoughtful and informed decisions in the present with the best information available to us. As so eloquently put in Profusion in Museums: A Report on Contemporary Collecting and Disposal (see Resources), “We are the future generations of the past, and decisions must always be made in the present.”

The best way to make these difficult decisions is to make the process visible. Inviting outside perspectives—through advisory panels, community groups, volunteers, or diverse staff—enriches museum decision-making, challenges conventional ways of thinking, and invites ideas or interpretations that staff may not have previously considered. For this to succeed, transparency is essential. But what does transparency look like?

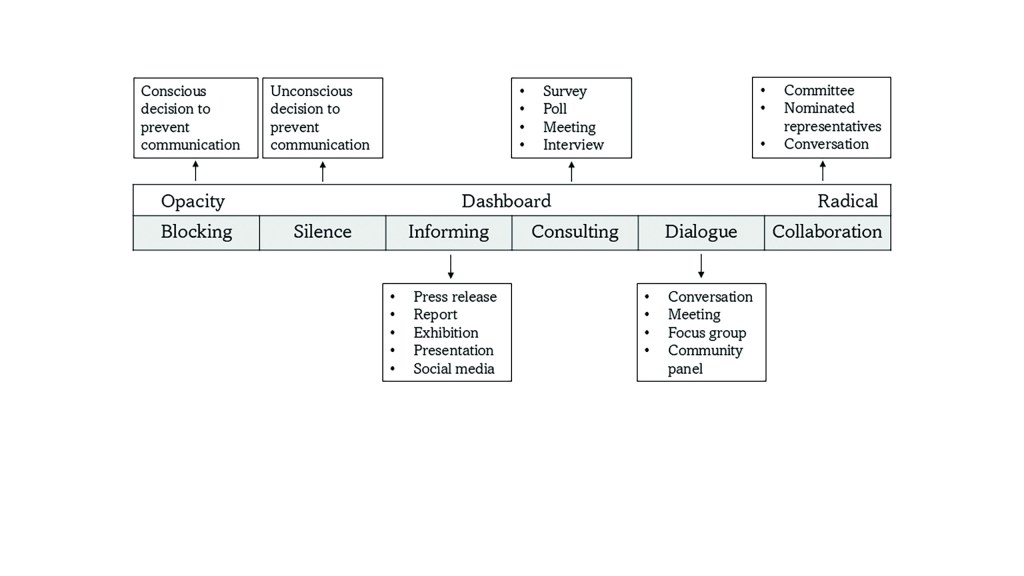

Dr. Janet Marstine, an eminent museum ethics expert, identifies two types of transparency: dashboard and radical. Dashboard transparency is superficial—information is shared but with no opportunity for deeper understanding or participation. For example, with dashboard transparency, a deaccessioning news story is posted on a museum’s website with no further explanation. In contrast, radical transparency, which invites involvement, is more desirable for ethical best practice. With radical transparency, the museum would let the public know that deaccessioning is happening; explain why; and offer options for participation, such as taking part in a survey or consultation, or details on whom to contact for further information.

At its core, transparency is not a tick-box exercise to show the museum is doing the right thing. It is an institutional choice to act with openness, honesty, and accountability.

Communication Is Key

Transparency hinges on thoughtful communication among staff, stakeholders, and audiences. For my book Deaccessioning Museum Objects, I created the Transparent Communication Model to help practitioners identify which audiences might be interested in witnessing or being involved in a deaccessioning process and then tailor the type of information shared accordingly. Audiences include museum professionals and stakeholders and the public, and types of outreach could include such things as a local news story, an in-gallery exhibition, a targeted consultation with key stakeholders, or technical reports to the board.

Conscious selection of information is essential (see chart above). Transparency does not mean all data needs to be shared with every audience, and there is an important difference between silence and actively choosing to withhold information. For example, the public may not need to know the financial value or storage location of an object. But everyone can know which objects are under consideration for removal and why.

If it has not occurred to museum professionals to share information, silence becomes the default action. For example, an audience may not be informed about a deaccessioning decision because it is perceived as uninterested in that particular object. However, silence can lead to accusations of conspiracy or wrongdoing. That said, it can be ethically appropriate not to share certain information deemed unsuitable for a specific audience. For example, museums may be legally prohibited from disclosing a donor’s name or address. Museums committed to transparency will acknowledge the existence of such information and explain why it cannot be shared.

What Does Ethical Deaccessioning Look Like?

Across the UK, museums are piloting approaches to make deaccessioning more inclusive, transparent, and participatory.

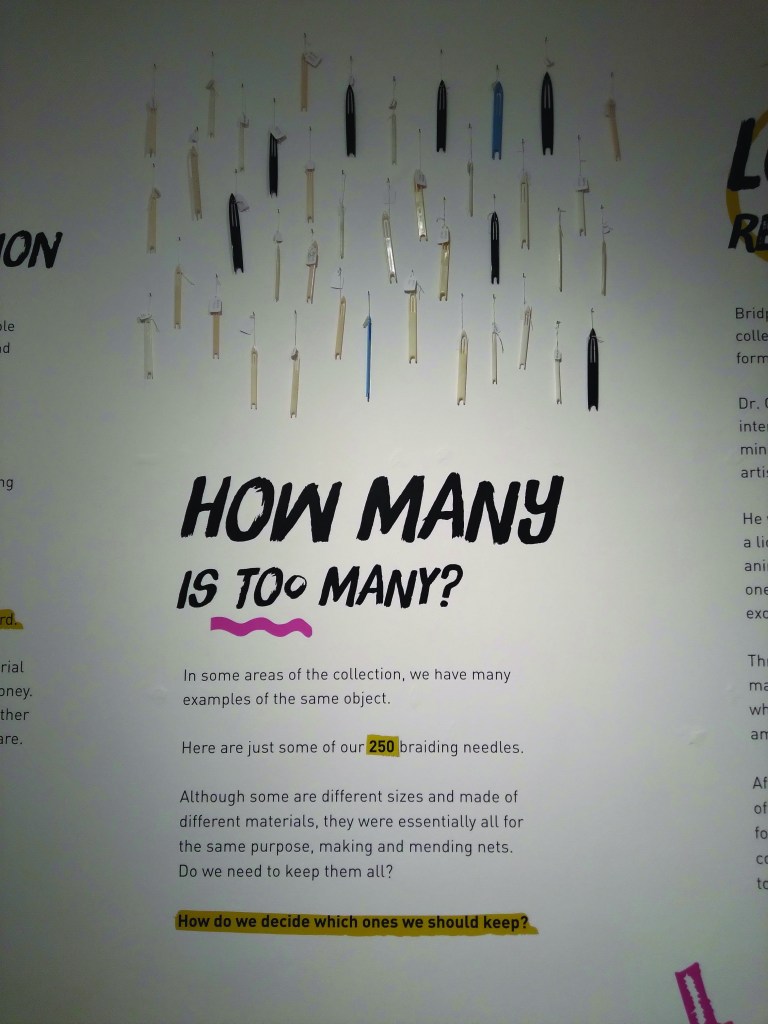

Bridport Museum in southwest England hosted a temporary exhibition, “The Right Stuff?,” that asked visitors “How many is too many?” and invited them to vote and comment on which items should remain in the collection.

MonLife Heritage, which operates six heritage sites in Wales, sold 400 objects from its agricultural and social history holdings at a local auction. But it also communicated clearly and publicly about the rationale and process behind the decision.

Manchester Art Gallery in northern England launched a program in which staff are working with local university students, community members, and artists to upcycle damaged or unusable objects into new artworks.

These approaches demonstrate a deep respect for the public’s relationship with museum collections. When museum audiences are invited “behind the scenes,” not just to see what’s being done but to understand why, museums build trust. In doing so, they create institutions better equipped to serve and be sustained by their communities well into the future.

Resources

Jennifer Durrant, “Understanding Disposal as an Ethical Crisis Response,” in Stefanie S. Jandl and Mark S. Gold (eds.) Collections and Deaccessioning: Towards a New Reality, 2021

Jennifer Durrant, Deaccessioning Museum Objects: Transparency and Ethics in Disposal Practice, 2025

Janet Marstine, “Situated Revelations: Radical Transparency in the Museum,” in Janet Marstine, Alexander A. Bauer, and Chelsea Haines (eds.) New Directions in Museum Ethics, 2013

Museums Association, Off the Shelf: A Toolkit for Ethical Transfer, Reuse and Disposal, 2023

Harald Fredheim, Sharon Macdonald, and Jennie Morgan, Profusion in Museums: A Report on Contemporary Collecting and Disposal, 2018

Dr. Jenny Durrant is a freelance consultant with nearly 25 years’ experience in curation and collections management. She is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and a member of the Museums Association Ethics Committee. Find out more at jennydurrant.co.uk or follow her on LinkedIn @Dr-Jenny-Durrant.