The theme of this year’s Alliance annual meeting is “storytelling.” However, if you are attending the meeting in Baltimore today, you probably aren’t reading the Blog! For those of you who can’t join us this year, recurring CFM guest blogger Zoe Mercer-Golden shares some thoughts on the power of storytelling, based most recently on her experience with Yale University Art Gallery

From the time I was small, I was teased about my love of stories: I eavesdropped on conversations at the grown-up table, snuck books into bathrooms when I became bored at parties, and acted in plays that I wrote with friends. Stories that I read and told shaped my life and continue to be central to who I am today.

I now tell stories in a different context: art museums. For the last three years, I have spent hundreds of hours researching and designing tours that tell the stories behind and around art objects. I share anecdotes about artists and the realities of their lives, and explain the political and social narratives surrounding different objects. If the piece in question makes reference to a particular text, myth or legend, I discuss the larger symbolic importance of that narrative to a people or a nation. These stories help the objects come alive for visitors, who are often looking for points of access for objects that come from unfamiliar cultures or time periods.

This past year, I have begun telling a new set of stories on my tours: the story of how objects entered museum collections. Within the clean, well-lit halls of art museums, we (those who work in art museums and those who visit them) tend to imagine that the stories behind the objects’ presence are as unmarked as the museums’ walls. The reality is far more complicated—often, in fact, quite distressing.

Last summer, I visited many of Europe’s greatest museums, principally in former imperial capitals. While the objects that I studied mostly had been removed from their countries of origin in the last three centuries, some had been removed even earlier. “Art appropriation,” the blanket term for the removal of objects or artistic styles from their original contexts, is by no means a new phenomenon: the ancient Mesopotamians practiced it, as did the Greeks, Romans and ancient Chinese. For the last three hundred years, art appropriation has been largely (though not exclusively) conducted by Western powers inside their colonial territories. Humans took and continue to take the artwork of other countries and cultures both to prove “I was here” and to signal their own cosmopolitan taste. Art appropriation demonstrates political power, social prestige and the capacity to mobilize on a massive scale.

The end result of these appropriations are massive museum collections full of objects that were stolen or purchased at absurdly low prices. While some objects were lovingly excavated by knowledgeable archeologists, many were excavated by under-trained researchers who were out for quick cash; others were simply lifted by wealthy travelers looking for souvenirs. Few objects and sites were left unscathed by dynamite and axes. War and colonialism left a bloody legacy behind, and facilitated the violent removal of beautiful works of art.

Contemporary museum collections thus present a serious problem: our museums contain objects that, for their educational and aesthetic value, we are loath to give up. Yet it is hard to avoid experiencing at least some residual feelings of guilt or shame when thinking about the way in which these objects entered museum collections. We now care about objects we don’t want to return that signal histories of oppression in which the museums that house them are implicated. How, then, can museums reconcile these histories with our current tortured awareness?

I have found that story-telling, and other self-reflective educational practices, while not a permanent or complete solution to this problem, is at least a beginning. People everywhere, most especially teachers and students, struggle with how to discuss the legacies of imperialism and colonialism. Telling stories in museums tied to concrete objects is a useful way to start difficult conversations about the parts of history many would like to efface or ignore.

Good facilitators of this conversation will make clear the strong arguments on both sides of the debate: those who demand the right of return did suffer violence and destruction, and have a strong claim to their cultural heritage; yet if we believe that cultural heritage is a global inheritance, we also acknowledge that all people have a right to learn from all cultures, and that global museums are rare places of cross-cultural dialogue. Sending all appropriated objects home would diminish museums in general, and might even harm the objects in question, even if maintaining the status quo seems unjust.

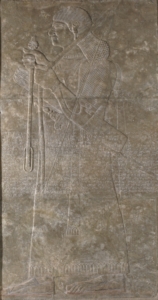

In the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery, we have a number of objects that can be used to as points of departure for these discussions, especially our ancient Assyrian reliefs from the palace of Assurnasirpal II in Kalhu. Removed by Protestant missionaries trying to prove the literal truth of the Book of Isaiah, the reliefs pay testament to a difficult time in American and European history—and to the continued heightened emotions that many people feel about that part of the world. My job as a teacher becomes using these reliefs to explain the many different imperial and cultural histories that are attached to these panels, and to the ways in which they have been re-purposed for centuries to mixed effect.

Art museums therefore become spaces in which conflicting claims to stewardship and ownership can be raised, in which objects take on significance greater than aesthetic or cultural symbolism. The stories that we tell in art museums don’t have to be simple: they can question the very fabric of museums themselves. Unless they acknowledge the complex histories of the objects they contain, museums will remain the conservative bastions they are often accused of being, and miss an opportunity to educate and people at home and abroad. Storytelling becomes a safe way for museums to engage with their own histories, and indeed, a way for museums to move forward with self-awareness and dignity.

Elizabeth Merritt