My colleague Elizabeth Merritt’s last blog post noted two facts in passing that deserve to be linked together more closely: the dominance of women in museum studies programs and the significant cadre of museum studies graduates who are “unhappy that they are underpaid compared to the jobs they could get with their level of education.”

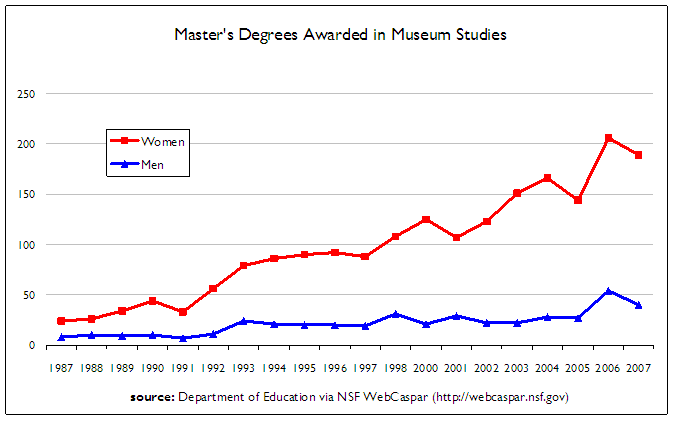

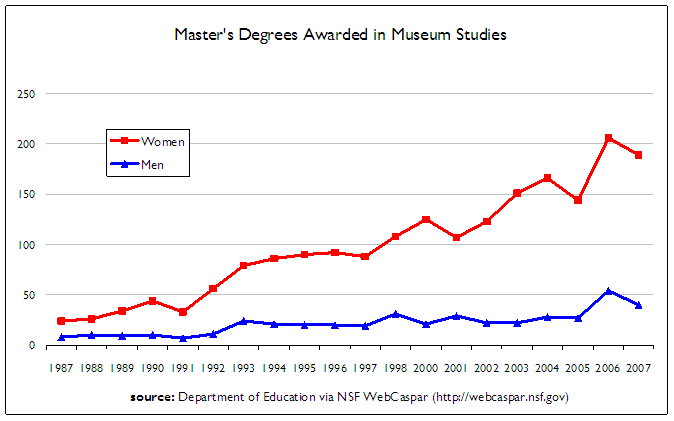

As a new study by Ohio State sociologist Donna Bobbitt-Zeher shows, the increasing feminization of any academic field can be (and usually is) associated with lower salaries. Bobbitt-Zeher also shows that “[college] majors that are more popular with women are becoming increasingly dominated by women”—which is just as true for masters-level programs like museum studies (see below) and public history. In other words, museum studies is part of the larger problem of academic gender segregation. As a result, museums should probably be thinking about ways to recruit more male employees and to encourage a better balance among the various academic domains with proactive counter-programming (e.g., more vigorous offerings of, say, science programs for little girls and humanities programs for little boys). These recruitment efforts should be part of the same pipeline from museum-struck 7-year-olds to museum workers. Plus, a higher percentage of male workers in museums could raise the salaries for everyone.

Also, here’s an addendum to Elizabeth’s suggestion that museums recruit employees more actively from their communities. It comes from a 1972 report that AAM prepared for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (Museums: Their New Audience):

“[Our Committee recommends] the institution of training programs designed to open careers in museum work to persons and groups who would otherwise never have the chance to even to consider such careers, these programs to aim at the very young as well as the more mature and to be aimed at eliminating the academic barrier.”

File under “some things never change.”

Phil Katz

Assistant Director for Research, AAM

that is bullshit…

Phil, I realize you are trying to be somewhat provocative, but I'm having trouble following your line of argument.

Leaving aside the question of museums studies programs, your argument seems to be: Since

1)the majority of museum professionals are female, and

2) men tend to be paid more, and

3) when a field becomes more female (such as academia), salaries are depressed, therefore:

We should hire more men and salaries for both men and women in the museum field will rise.

Even not counting the overall societal trend (c.f. Lilly Ledbetter, etc, etc)I'm not sure I understand the logic, i.e. that Bobbitt-Zeher's study would hold in reverse.

I am fairly sure that museums don't have the resources to pay high salaries, and are not choosing to pay low salaries simply because women make up the majority of workers. Also, the last two posts on this bog are somewhat contradictory. First it's written that museums should recruit people from low-income families right out of highschool and college so that museums can still pay less and the employees will be satisfied. Then in this post you write that museums need to pay more. I understand that the posts were written by two different people, but as an organization AAM should have a clear idea and goal.

Honestly, anyone going into museums knows that that the salary will be awful. They should be prepared for that when entering the field. I'll be starting my M.A. soon, and I know I will be paying off my loans for the rest of my life. I'm going anyway so that I can have a job I love. The posts here are very discouraging for a young professional just starting out. It seems like I am exactly the type of person you don't want working in a museum (white, female, upper-middle class) despite my qualifications and passion for educating the public through museums.

Why is there so much concern about recruiting new people to the field when there are so many qualified individuals who cannot find jobs? Let's employ people with degrees and training first, then worry about the next generation of employees.

The recent blog posts have been very discouraging for me. I am about to start a master's program in museum studies this fall. I am disappointed and consequently anxious to hear that the field is suggesting to bypass those with a fervent academic interest in museums and museum work to recruit individuals who have no existing interest in museums or an academic background which addresses the educational mission of the museum.

I think it is important to employ individuals in museum who have a wide range of skills, addresses toward learning, cultural perspectives and awareness, and experience in the field. However, collegiate education is NOT something to be overlooked. My undergraduate academic background has complemented my ability to teach, engage visitors, and explore program niches for the school children, members, visitors, and other people who the museum I worked with could serve. I am hoping my master's program will further this background to enable me the ontological understanding of museums, museum approaches, social connections, and experience necessary to be a representative of the field and the institution through which I will educate and engage the public who participate.

A museum studies degree should not automatically secure you a job in a museum, but combined with internships, previous employments, cultivated skills and interests, and action in the field, it should.

What is the value of a master's degree to all of you bloggers reading this? Have any of you had success working in the field without a degree?

Do you work with your passions? Do you make financial ends meet? Are you happy with the work you do? Have you affected the community in which you participate?

I went to school to be a teacher. I taught for six ears and in my tenure used museums and cultural sites extensively in my instruction.

I moved to a rural area that has three main areas to work. The Hospital, the school and The State Police. If you can trace your ancestry back at least 100 years you might be lucky enough to be employed in those fields.

I ended up working at a museum. I started as consultant for National History Day and now I am the Associate Director of Education.

I am a man. I think I probably make decent museum money all things considered.

I hire people. I prefer people who understand the importance of the profession and who work like a teacher. 24-7.Museum studies people are people I like to look into first.

I am a museum studies student. I find it fascinating and tedious depending on the day of the week or the content. I love learning, admin stuff, and education and visitor studies but quite frankly don't get the obsession with stuff or why our industry is run by curators.(Please don't respond. I understand the ARGUMENTS and acknowledge their importance. I don't get the culture of the veneration)

Museums can stand to have their chains rattled. MS students (including myself) need to understand that there are people from private industry, public education, and non-profits who can bring in a lot to the profession by not being indoctrinated in the traditional fashion.

Second career people when moving on for the right reasons can be very productive hires. Hiring from the community may mean retention, but it can also mean stagnation.

There are no one sided answers here. Places that succeed integrate hard working, knowledgeable people with a passion for what they do. Schools are only as good as the people who attend them. And museums are only as good as the people who work for them.

In response to Kate —

Mea culpa: I'll admit to some logical legerdemain for the sake of provocation (and blog-like brevity). Also, I'm still trying to get a grip on the complex dynamics of the museum workforce, so I appreciate the chance to restate and rethink the pieces of my original argument. I hope this is clearer.

Here are the facts, as I understand them:

1) All other factors being equal, college graduates who major in academic disciplines dominated by woman historically go on to earn less than graduates who major in fields dominated by men or with a gender balance. (That is the gist of Bobbitt-Zeher's paper, if the press account can be trusted.) Because college precedes a career, the link may well be causal. My own research on the professional development of historians and museum workers suggests that the same is true for post-baccalaureate degree programs, though the presumption of a causal link is much weaker as people often go back to graduate programs partway through their careers.

2) Professional fields that have become "feminized" often (but not always) experience suppressed wages. A good discussion of this is Lynn Hunt, "Democratization and Decline? The Consequences of Demographic Change in the Humanities," in Alvin Kernan, ed., What's Happened to the Humanities? (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 17–31 (excerpted at http://www.historians.org/Perspectives/issues/1998/9805/9805VIE1.CFM). Again, it is not clear whether the "feminization" causes suppressed wages or whether suppressed wages convince men to abandon these fields — scholars have presented both theories.

3) Many academic disciplines have experienced a "tipping point" phenomenon: once they reach a certain percentage of women as students (or professors, or practitioners), the percentage of women in the field begins to grow even more rapidly. Thus, "majors that are more popular with women are becoming increasingly dominated by women" (to quote again the report on Bobbitt-Zeher's research).

4) The museum field has demonstrated evidence of all three of these trends: an accelerating proportion of women as museum employees, a growing dominance of women among the ranks of museum studies graduates, and endemic complaints about suppressed wages (though it is not clear to me that museum wages are necessarily lower than wages in other non-unionized arts or nonprofit sectors).

Given these facts, here are some of the implications:

1) A good way, in the long run, to increase the relative wages of museum workers would be to encourage a gender balance in those academic fields from which museum employees are drawn. Hence, early intervention to encourage young boys or girls to pursue studies in areas where men or women are currently underrepresented.

2) We should identify the "pull factors" that increasingly (and disproportionately) attract women to the museum field and the "push factors" that likewise discourage men from entering the museum field. These factors may not be directly related — and they may not be causally related to wages — but let's find out. (There are other other diversity and equity implications in the gender balance of the museum workforce, which I'll let others address.)

3) If a growing preponderance of women in the museum field is having an impact on wages, then hiring more men really should increase the aggregate wages for all museum workers.

Hello again Phil–

I'm glad you took the time to make your argument a bit clearer. While we don't do pay equity research here at ILI, I still feel there are some unsupported assertions in your post.

While I can see that there is an increased feminization of certain fields, and definitely an increase in museum studies degrees to women, you don't present any evidence that museums professional were not already primarily female. One central aspect of your argument that this is a new trend for museums, when I'm not convinced the data would support that.

Alternative explanations could account for that chart, such as perhaps those females who were already within the museum field, or likely to go into that field are now becoming accredited. therefore a hypothesis instead of increased professionalization.

Thus your later points 1, 2, and 3 may or may not be true, but you haven't presented any evidence that the field is becoming increasingly populated by women, you simply state it is true in point 4.

Likewise, you don't provide any evidence that increasing the numbers of males, or even creating a better gender balance, actually raises the wages of females, in the museum industry or in any other more traditionally female populated workplace. So I fail to see how the second set of points follow. I could easily make the reverse argument that increased numbers of men in the profession might only further depress the female salaries.

Of course, each of these arguments ignores significant other variables at play– that the nature of education and academia, and the humanities in particular, are changing dramatically, both related to and independently of, the economic crisis.

While we could continue to debate how significantly museums have attempted to, for instance create a science pipeline for girls (there is wonderful NSF/ASTC data on that), I'd rather hear more on how you support your central point. It's an interesting stand for a leadership organization to make, so I want to make sure I understand it clearly.

Kate

Or, it would be great if museum professionals could get paid according to the value of the work we do. No one is in this to get rich, but it would be nice to at least be able to live. Furthermore, I think maybe if people knew more about what the field accomplishes, then it would get more attention, and possibly more funding.

Everyone: sorry about the blank comment above!

In reply to Kate:

Thank you for this engaging conversation — which is exactly the purpose of the Center for the Future of Museums and this blog! Please note, however, that my comments about the gender imbalance in the museum field (much less my recommendations for addressing the imbalance) do not represent an official position statement by the American Association of Museums.

To quickly address one of the substantive points in your last comment: You write that I "don't provide evidence that museums professional were not already primarily female." Indeed, women have been a majority of the museum workforce for many years — but a survey of AAM members conducted in 2007 shows that the percentage of female members grows smaller with age, so that younger AAM members (more recent entrants to the field, in most cases) are much more likely to be female than older, more veteran members. I think this is representative of the museum workforce as a whole.

I don't see anything about gender in those articles that isn't a predictable result of the general increase of women in academia. What would show an acceleration or "tipping point" effect would be a change in the rate at which men and women in college get degrees in a program as a portion of the total number of men and women getting degrees. None of the articles or charts show that acceleration.

Programs most popular with women will also be expected to grow fastest in total students compared to other programs. Absent other factors, this would lead to increased competitiveness for jobs and depressed wages for graduates. Also, because average salary of a major is determined after the fact based on later careers, gender inequity in the workplace is a reasonable causal explanation for lower average wages in increasingly female dominated majors.

Looking at the data on Masters degrees in Museum Studies, the drama disappears when you control for the general increase in women in academia. The chart shows that museum studies programs grew immensely in popularity — from roughly 12 degrees per 100,000 total to roughly 36 per 100,000. It also reflects a growth of women in academia during the period. Further, the data reflects that a randomly chosen women with a masters degree is about three-and-a-half times as likely to have it in museum studies as a randomly chosen man with a masters degree throughout the whole period. It's very noisy, but no gender-based acceleration appears present in the data.

The public history data shows men getting history degrees at roughly twice the rate of women throughout the period without a visible acceleration. Progressively increasing percentages of women getting degrees would also seem to explain gender differences by length of AAM membership.

Getting back to the central proposal to increase wages by increasing wages in the field by recruiting more men, it seems like it would rely on gender inequity to raise the average wage and then gender equity to raise wages of existing workers rather than increasing the spread of wages. That, after somehow increasing the money available for wages and overcoming the downward pressure on wages from increased recruitment.

But most importantly, I think these are the wrong questions being asked. Wages are known to be a very weak indicator of job satisfaction. Even if it is harder to study and o explain, the better questions to ask are: Does a museum studies degree lead to greater job satisfaction compared to other museum workers or those with other graduate degrees? Do museum workers have greater job satisfaction than others with similar wages or educational attainment?

An intriguing side question has entered my head though. Despite having been a majority of museum workers, have women been historically underrepresented in the field based on expressed preference?

Paul Koenig

pdkoenig@variablearts.com–

Here's a link to an article I wrote for AAM's Museum that addresses this topic and provides some statistics:

https://www.aam-us.org/pubs/mn/gender.cfm

Marjorie Schwarzer