This article originally appeared in the July/August 2010 edition of Museum magazine.

What Can They Teach Us About Exhibit Development?

I know it’s hard to believe, but I voluntarily left a glamorous career in the film business to work in the wonderful world of museums. Admittedly, it resulted in a “slight” decrease in salary, and I don’t get to eat lunch at the Ivy with studio executives anymore, but creating museum exhibits is a lot more fulfilling and much less stressful. Fortunately, in 1999 Abbie Chessler of Quatrefoil Associates saw my skills in screenplay development and film production as an asset to exhibit design; otherwise, I’d be punching some Hollywood agent in the nose about now.

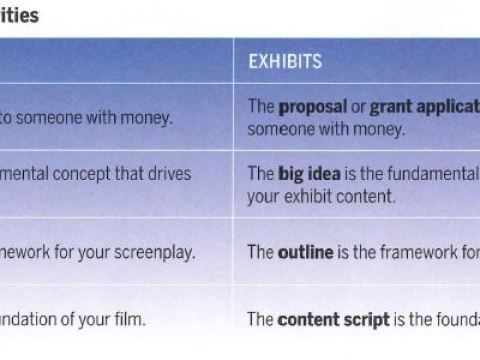

It didn’t take me long to recognize the similarities between good filmmaking and good exhibit design. Both start with an idea that is developed into a project, both require funding and both are created for the audience/visitor, not for the people creating them. The successful ones also share great writing, direction, and visual design that come together seamlessly to create a memorable experience.

The foundation for a hit movie is the screenplay. I’ve read a few brilliant ones in my day, but most of the thousand or so scripts I’ve encountered were forgettable. As I look back, I think about what made one better than another. A well-written screenplay has a storyline that follows a premeditated path; characters, scenes, and storylines that connect and tie back to each other; a structured yet unpredictable story arc; and an opening that quickly grabs your interest while setting the tone. Another attribute is brevity—every scene, line of dialogue and character has a purpose that moves the story forward. Nothing is superfluous. It’s 120 pages of pure function.

Similarly, the basis for a successful interpretive exhibit is the content script, which should be well defined at the very beginning of the project and followed throughout. Design should be based on the story content, not vice versa. Since museums are competing with so many forms of media and entertainment, a gripping, premeditated storyline is a perfect strategy to grab and maintain visitor interest. A great screenplay is a “page-turner.” You can’t wait to see what happens next. So why shouldn’t an interpretive exhibit be a story-driven “pageturner?” Remember, premeditated does not mean linear. Many movies (such as Crash and It’s a Wonderful Life) follow a non-linear path, as do most interpretive exhibits. A random plan does not mean random thought.

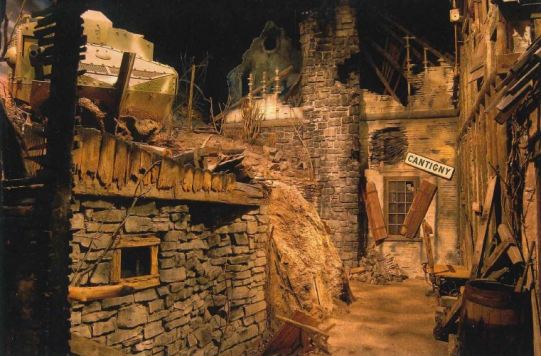

When flipping through stacks of scripts, the ones that grabbed my interest within the first few pages were the ones I always read first. A clever opening gave me hope that the remaining screenplay would be worth my time. Museum exhibits also offer wonderful opportunities for dramatic openings. Use those opportunities to your advantage. We live in a world of snap judgments, so grab those visitors at the very beginning and then provide them with an enticing trail to maintain their interest. At the First Division Museum in Wheaton, Ill., visitors are immersed in the experience of World War I as they enter the simulated bombed-out village of Cantigny, France, and continue to a trench with an armored tank teetering overhead. Talk about drawing visitors into an exhibit. Another dramatic entrance is located at the Page Museum in Los Angeles. As you drive by on Wilshire Boulevard, you see a. giant mammoth stuck in a lake of tar. If that doesn’t pique your interest, I don’t know what will.

Editing. Chopping. Cutting. Slicing. It’s as difficult to do in screenwriting as it is in exhibit development. You write the best scene of your life, but when you step back and look at your screenplay, you realize the scene doesn’t move your story forward. It’s captivating … but extraneous—and it has to go. The same editing needs to occur with exhibit development. Find your story and its supporting materials, create the interpretive text and interactives that enhance it, tie these all together—and say a sad farewell to everything else. Perform these steps early in your content script, not as you go into fabrication; otherwise, you’ll end up with missing pieces to your storyline. Have you ever watched a movie and felt that something important was left out, or wondered why a character was never seen again? That’s because a script was too long and wasn’t fixed in pre-production. Chunks were edited out much later—”in post,” to use studio jargon—to shorten the running time. That “we’ll fix it in post” attitude ruins both movies and interpretive exhibits.

Good character writing creates multidimensional, interesting people who change or grow and have dynamic relationships with other characters throughout the script. They are often people your audience can relate to or connect with. Sometimes they’re despicable or terrifying. Think back to film characters you’ve encountered over the years. What made them so memorable? Luke Skywalker, Michael Corleone and Hannibal Lecter remain recognizable names to this day. And Scarlett O’Hara: Now, there’s a complex personality with dynamic relationships—perhaps even a metaphor for the Civil War.

In museums (and movies), a character doesn’t have to be human. Artifacts, events, bacteria or the atom bomb can all be characters. Select ones that convey a story and connect to other “characters” in your exhibit. And don’t be afraid to exploit controversy. It makes for very juicy storytelling.

In a screenplay, good dialogue defines your individual characters. It is appropriate to the period and to the audience, but it does not tell your story. Within a few sentences, you should be able to discern a character’s gender, education

and social status without the aid of a description. The same goes for period dialogue. Modern words or delivery in a period movie are akin to a slap in the face. Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves is a good example of this phenomenon. There you are, taken back in time to Sherwood Forest, with Englishmen in tights, magically swept away … until Kevin Costner opens his mouth. Oops. Guess we’re not in Merrie Olde England anymore. This dramatic lapse doesn’t just occur with dialogue—it happens when anything in a movie or exhibit rings untrue.

In museums, dialogue is the voice of your exhibit, usually in the form of text. Think of what you want to convey. Historical text should have a different feel than scientific text. How are you going to handle dialogue so that it is

appropriate to your entire audience? Trying to write for everybody is a screenwriting sin. Films and exhibits should always have a target audience. If the target is “families with young children,” animated features are a good source

of inspiration. The story is told on a very basic level for the kids, but witty zingers are thrown in to keep the adults entertained.

Even better than exhibit text is an interactive experience. In filmmaking, dialogue becomes the kiss of screenwriting death if it is used to describe a character, background story or event. Use this principle in your exhibit medium by not relying on text-crammed graphic panels to deliver your content. Don’t limit the expansive storytelling ability of your exhibit by turning it into a book on the wall.

Screenwriters use a multitude of literary devices to manipulate and enhance the audience experience. Classic techniques such as the flashback, suspense building and foreshadowing take the audience experience to the next level. I recently asked a group of museum professionals if they could name an interpretive exhibit that used these

techniques. The room shrugged. I then asked, “If suspense and flashbacks help grab audiences, why aren’t we using these cinematic tricks in more museums?”

Was that the last straw for some of you? The naysayers are probably muttering, “Are you nuts? You’re trying to compare films and exhibits when they’re nothing alike! They’re apples and oranges!” Not only do I hear you, I agree

that films and exhibits are two entirely different media. In fact, they should never be confused with each other, or any other medium.

Surviving the Economic Downturn

How does the movie world typically fare during financial hard times, and what can museums learn from such trends?

The feature film industry may not be recession-proof, but it is generally more recession-resistant than other businesses. Rumor has it that people see more movies during times of economic crisis. Movies are still reasonably affordable, they’re great for dates and family outings, and they provide a few hours of escapism from our bleak lives.

Family-oriented fare tends to be the most popular during economic slumps. Comedies, animated features and fun action films usually pull in the biggest audiences. Of course, economic recession also results in a plague of sequels, remakes, and television rehashes. As money dwindles, the studios become very careful with their investments. Name recognition for titles like Get Smart or Spiderman 3 provides a sense of safety for skittish creative executives. Completely unknown films are a bigger risk for the studios.

At the beginning of our most recent economic downturn, museums and visitor centers tightened their belts and prepared for the worst. Funding became scarce, but guess what? In 2009, 57.4 percent of museums throughout the \ country actually experienced an increase in attendance, according to a 2010 AAM report. It seems that, like movies, museums and visitor centers are great modes of escapism. Most are reasonably priced, provide family entertainment in a social environment and are usually a local destination.

During times of dwindling funds, museums can do a few things to maintain a healthy visitorship. For one, freshen what already exists. A few small additions and improvements can really spruce up a tired exhibit and make it seem like new. Create special programs, brainstorm clever ideas for marketing and advertising—anything that will help bring people in during these tough times. And you can always take advantage of the slow-down to plan for the future. Funding will eventually become available, so get a head start on the competition.

And here’s some more food for thought. At the beginning of the Great Depression, audiences flooded the movie theaters. Were people schilling out their last dime to temporarily escape their financial woes, or was it simply the novelty of “talkies” that drew the crowds? Since box office numbers decreased as the years went on, I suspect the fascination with something new was an irresistible force. So maybe clinging to the same old thing isn’t the key to financial security.

Remember when Star Wars came out? Talk about innovative! When George Lucas made his pitch, his ideas had never been conceived before, let alone made into a movie. No Hollywood studio wanted to take such a risk … except for one. Alan Ladd Jr., then president of 20th Century Fox, was willing to stick his neck out. Fox produced Star Wars … and the rest is history.

So keep that in mind when you’re freshening up an exhibit: Make it innovative, competitive and irresistible. Take a chance and go for it!

Nor does one successful medium always translate into another. For example, books and plays are not always successful source material for screenplays. Tom Wolfe wrote two critically acclaimed, best-selling novels that were made into movies: The Right Stuff and The Bonfire of the Vanities. The Right Stuff translated into a great film because it had an exciting story filled with historic drama, heroic characters and lots of action-packed visuals. The Bonfire of the Vanities, on the other hand, had none of the above. The book was a great read because of Wolfe’s prose and descriptive writing:

“[Sherman] gave the leash another jerk and then kept pulling for all he was worth. The dog slid forward a couple of feet. He slid! He wouldn’t walk. He wouldn’t give up. The beast’s center of gravity seemed to be at the middle of the earth. It was like trying to drag a sled with a pile of bricks on it.”

Without those wonderful words, which happened to be a foreshadowing of things to come, the audience was left with Tom Hanks attempting to take a wiener dog for a walk. When the prose-less plot combined with a cast of really unappealing characters, the result was a major box office flop. What exhibit development lesson can we extract from this blunder? It’s simple. Understand your medium and how it is meant to deliver your story.

Films are restricted to telling a story through audiovisual delivery in a non-interactive group. The audience is seated for two hours, watching a storyline with pre-determined pacing from beginning to end. Interpretive museum exhibits have the freedom to tell stories through objects, people and events in an experience that can include all the senses.

Visitors can come and go as they please, skip entire areas, view sections in any random order, at any speed, in an individual or group setting, with or without interactivity. Wow.

I’ve mentioned one of Hollywood’s more embarrassing failings so that you may learn from others’ highly expensive mistakes. I will now share the secret (okay, not-so-secret) formula for many other box office flops. Keep this recipe in mind when creating your next interpretive exhibit. It translates well—you just have to trade out a few words.

Step 1: Allow a big group of bean-counting studio executives to tell the writer how to be more creative.

Step 2: When the original writer doesn’t grasp the “creativity” of the executives, fire that writer and hire several more.

Step 3: Add a dozen more rewrites so the original script becomes completely unrecognizable and disjointed.

Step 4: Hire a young director who is willing to shoot all 158 pages of the rewritten script because he can “fix it in post.”

Step 5: Expect the editor (in post) to delete 45 minutes worth of scenes while maintaining a semi-coherent storyline.

Step 6: Assemble an inappropriate marketing audience to critique the movie and advise the producer as to how to make it better.

Does this sound ridiculous? It should. It’s why I left Hollywood.

Comments