Today’s guest post comes from Phil Katz, the Alliance’s assistant director for research and co-conspirator on many CFM research projects.

|

| Tomorrow andBeyond |

There’s nothing new about the prediction that technology is going to remake education, soon and dramatically: education reformers and tech entrepreneurs have been making this claim since at least the 1920s. Last week the Brookings Institution – a nonpartisan think tank based here in Washington, DC – joined the long march of predictions with a thoughtful and reference-packed report on Education Technology Success Stories. The report was produced by the Center for Technology Innovation at Brookings with support from the Gates Foundation.

Brookings also hosted a public forum on the future of education technology last week, which you can watch at http://www.brookings.edu/events/2013/03/20-education-technology. (Make sure you stay tuned to the very end, so you can hear me ask a question and introduce the word “museum” into the conversation!) The focus of both the report and forum is formal education, mostly in classroom settings. But the key questions at stake – “How can educators incorporate the latest technologies to improve education and assess what proves effective?” – apply just as well to museum education.

The report features five “education technology success stories.” For each story, they could have added a museum variant:

- Robot Assisted Language Learning(RALL), in the form of kid-friendly interactive robots already being used to teach English to some young children in South Korea. (South Korea is also the world leader in robot docents for museums.)

|

| Robot teachers in Korea |

- Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), which nearly everyone these days is describing as a disruptive force in higher ed. (Including the team here at CFM, in our new TrendsWatch 2013 report, which looks at MOOCs through a museum lens.)

- Minecraft, a web-based “sandbox” game that students and teachers are using to create simulated worlds that model the laws of physics, chemistry and environmental science; the game can even be used to recreate historic sites. (The American Museum of Natural History has also used Minecraft to help high school-age visitors explore the science and politics of food.)

- Computerized Adaptive Testing, touted as the latest replacement for old-fashioned multiple-choice tests, a way to relieve teachers from the burden of correcting bubble sheets or even student essays, and a tool for self-paced instruction. (OK, I’m not sure what the right museum analogy is for this one — any suggestions, readers?

- Stealth Assessments, i.e., formative assessments embedded in games, with no pressure on the players/students. At the public forum, Valerie Shute, an education professor at Florida State, described an experiment that used an off-the-shelf video game (Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion) to track problem-solving skills that are part of the formal curriculum. (How teachers will usethe assessment information for student evaluation is an open question, and not every lesson can be turned into a computer game.)

Gaming and assessment are two areas where the Brookings publication would especially have benefitted from looking at museums and building on the expertise of museum educators and evaluators (who have been tackling the problem of assessing relatively brief and bounded learning experiences for many years). Although the report begins with the traditional claim that “the next generation of education technologies is facilitating substantial change,” I think it makes a good case that the confluence of new presentation technologies, new assessment technologies and new technologies to recognize student achievement (like digital badges) could really amount to something … well, new.

This became even clearer after the public forum, which still left me with two questions:

- Why are (nearly) all the examples of education technology success stories drawn from STEM subjects? Where are the examples of education technology that improves historical understanding and sharpens moral reasoning? And how would you assess that kind of learning?

- How do these innovations from formal education settings apply to informal learning? And does interactive technology make formal learning more “informal” (even museum-like).

Go to the videotape and watch the answers from the panel at the forum — but don’t get your hopes up. Can we provide better answers?

Regarding the frequency of which STEM based institutions are often at the center of these discussions, I have often wondered this myself and look forward to comments from other readers. While the vast majority of my career has been informal science education, and I can hypothesize along with the rest of our community drawing connections to the natural analytic and experimental nature of those in the sciences, I think that's an easy, reductionistic answer… and would love to see some stimulating dialogue on the topic!

Museums are an excellent tool for children and adolescents for learning experiences. The crime museum for example offers a complete look into crime and punishment. For many kids, this opens up many doors of opportunities for career ideas.

This article is efficient. Thank you for sharing it with us. I am visiting this blog on a daily basis and I am finding so much helpful article each time. Keep working on this and thank you once again. xnxx

nice post, rly usefull

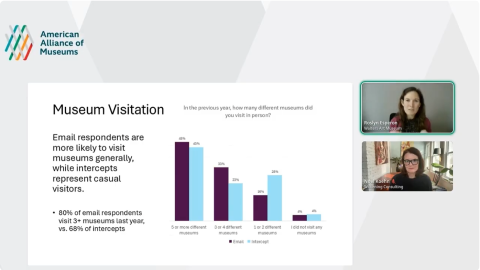

The infographics show that we spend on training, in relation to the rest of the activity. We can trace how this share increases over the last century, and grows in the future. Also we can see how the share of learning changes with age, taking more and more time. We begin to learn at an earlier age, do not stop at maturity, and continue in old age.

Thank you for this inspirational post! The future is so near, and technologies are developing so fast… wow!

Good post guys!