Technology is fueling personalization of products, services, communications and experiences. We explored some of the implications of this trend in TrendsWatch 2015, but the impact and potential of “personal” continues to grow, nowhere more so than in the realm of education. Personalized learning has been hailed as a solution to the “one size fits all” approach that predominates in today’s classrooms, and demonized as an excuse to park children in front of computers and minimize the role of skilled teachers. What does the growing interest in personalized learning mean for museums? Ashley Weinard is in a good position to tackle that question, as an educator with twenty years of experience in the museum field currently serving as education technology manager at The Hill Center in Durham, North Carolina. Follow Ashley and The Hill Center on Twitter!

Museums are all about celebrating the individual. Our institutions are built to share and memorialize ideas, solutions, accomplishments and works of art created by individuals over time. From my new vantage point, though, I am beginning to wonder how well we serve the diverse needs of individual museum learners. Have we mistakenly assumed that our visitors learn in the same way, clustered near a mythical average, when actually the spectrum of learning is much broader?

After 20 years of designing museum learning experiences, I stepped outside our field to work with a lab school that serves struggling learners, and found that designing personalized learning technologies gave me a new perspective on education. Even though the children I encounter all struggle, they each confront different issues. Most have a diagnosed learning disorder, but those disorders play out differently in each of their lives. Each kid receives personalized instruction, each experiences their own pacing and progress. Their accomplishments are unique. In the outside world, these children are labeled with LD (Learning Disabled) or EC (Exceptional Child) classifications. Inside my school, we call each individual learner by name.

Museums often design learning experiences based upon generalized information—age, grade-level, developmental stage, curriculum standards, and other demographics. Since we don’t often have the funding or time to build relationships with individual learners and assess their personal strengths, we construct tours, drop-in programs, and interpretive materials based on categories. For example, in many museums, learners are often randomly grouped, assigneda museum facilitator, and asked to engage with materials and activities developed for the average learner. The facilitator does his or her best to adapt the experience on the fly based on whatever information he or she can glean about the learners upon first impression. It’s a tough job. How often are we left at the end of the experience wondering, “Did anyone get anything out of that?”

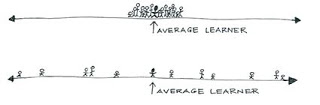

Dr. Todd Rose, Director of the Mind, Brain, and Education Program at Harvard University and President of the Center for Individual Opportunity says, “if we have designed learning environments [or experiences] based on average, the odds are we have designed them for nobody.” Diverse learning styles and variability are the norm today, not the exception. Rose refutes the “Myth of Average” by explaining that all learners have what he calls a jagged learning profile, an individualized mix of strengths and challenges. No one fits easily into categories like struggling, normal, gifted. We must admit, embrace, and celebrate the fact that each of us is all of those.

So if designing to the average is not productive, how can museums begin to design for the individual learner? The National Center for Universal Design for Learning (UDL) provides some helpful recommendations. Their suggestions are based on predictable dimensions, rather than individual need. These dimensions outline differences in the ways learners:

- Represent information.

- Engage with material.

- Act upon material and show what they know.

UDL’s three dimensions of variability can be used as guide to help us create a more multi-sensory approach to content, develop a broader set of engagement strategies for each learning experience, and expand our expectations for how learners will respond.

CAST, a non-profit researching and advancing universal design for learning, has gone further to develop research-based guidelines and checkpointsfor these dimensions of variability, which we can use as a tool to assess current museum learning environments and experiences and help design for future flexibility.

Thanks to new research and toolkits like these, we can begin to predict and plan for learner variability. However, for museums to be truly welcoming of all learners we have to be able to respond to their needs in the moment, as well. What more do we need to know about our learners in order to meet them where they are? How will we adapt our museum programming and spaces so we can be that nimble? Given the limits of the museum, how responsive and personal can we actually become?

We can take some cues from adaptive learning, a developing technology that delivers individualized instruction based on the learner’s progress, needs, and preference. Adaptive technology responds to learners in real time by:

- Changing content.

- Changing assessment.

- Changing the sequencing of the material.

This type of technology puts learners in control of their learning path. They set personal goals and then their actions and responses determine what they see and learn next. These tools use predictive analytics to continuously collect data, analyze it, and adjust the sequencing of skills or content for that individual. The tools use that same data to improve the product for the next learner.

One might say this is not all that different from how museum educators and facilitators interact with museum learners now. (Think back to that facilitator I described adapting on the fly.) However, I think it is different in two critically important ways. The first distinction is that adaptive learning requires the facilitator to let go of control. The learning process–and sometimes even the outcome–is determined by the learner, not the facilitator. We can create a rich array of content and plan for all imaginable pathways, but each learner’s choice and progress along that path will be unpredictable. And, that might be ok.

The second distinction is that individual learner data is continuously collected and analyzed. Next steps along the path are not based on a set of assumptions or cues. They are determined by learner actions which have been carefully captured, reviewed, and acted upon in real-time.

There are technological tools on the horizon that will help us to respond to and design for learners in the museum environment. But even now, the concepts and routines of universal design and adaptive learning can be applied and help us rethink and improve our practices today. Why wait? It’s time for museums to create our own solutions for supporting and celebrating the individual.

My perception, over 30 years of museum work, is that many museum-based educators have long ago moved beyond the "average" learner paradigm. The constructivist learning models propounded variously by John Dewey, George Hein, et al, and the contributions of Lynn Dierking and John Falk, among others, have all helped us to see that museums are "free choice" learning environments where the learner directs the quality, depth and variety of what they may learn. Moreover, the reality that, for most museum goers the museum experience is social and not isolated in nature, has also informed the pedagogy. Strategies for diversifying museum experiences for a variety of learning styles and layering information have been discussed, researched and implemented in countless museums. The best museums have been places designed as fertile personalized learning environments in a social context.

The problem, it seems to me, is in how these experiences are assessed. We have to build evaluative measures that reach beyond minimal content acquisition to more elastic frameworks of value. Logically, if every learner learns a bit differently, then learning outcomes are bound to be different too.

Good point, Dan! Museums offer a remarkable range of learning experiences and choices that are unparalleled in today's education ecosystem. Specifically, museums are unique in the ways they spur visitors to share individual perspectives and construct personal meaning. What additional resources, staff capacity, or tools do we need to extend that privilege to all of our learners, not just categories of learners?

For example, we often encourage visitors to respond in personal ways to our collections through dialogue or written text. For some, that might be a challenge that requires scaffolding, a different method for communicating ideas, and possibly a goal adjustment. Are museums nimble enough yet to be able to hear/assess that level of need and have the tools to respond in the moment? Is that responsiveness critical? If so, what do we need in order to achieve that level of service?

The social element of museum learning you rightly bring up may be key in helping museums offer a unique solution to this dilemma. How might we foster a peer-supported model for personalized learning? How might we create spaces that encourage learners to independently or collaboratively adapt material and ultimately design their own learning experience?