Hi, Nicole here! Throughout the course of my work on museums and labor at CFM this past year, I have had the pleasure of talking with—and learning from—colleagues across the US in various stages of their careers. Time and again, I’ve heard from museum professionals about the importance of fostering equitable access along the pathway to museum employment. Students, new professionals, and people with long-standing experience in the field have repeatedly, and often passionately, expressed their desire to make museum work more inclusive of our country’s ever-diversifying demographics.

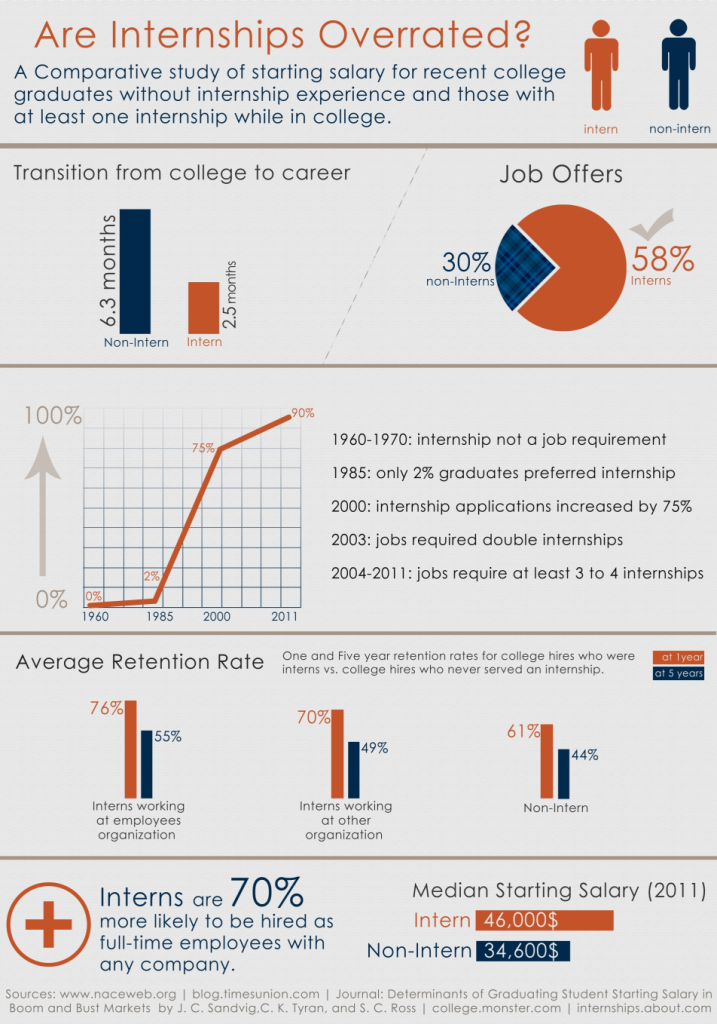

In these discussions, the subject of internships has emerged as one primary place in the museum employment pipeline where opportunities are narrowed and diversity is compromised. As Ford Foundation president Darren Walker observed in a recent New York Times piece, internships–and the networking that often secures them—can “reinforce the dynamics that create inequality.” He writes, “We often hear that success is ‘all about the people you know’—as if it’s just a matter of equal-opportunity relationship building. We rarely talk about…the privilege that has become a prerequisite to knowing the right people.” Internships, Walker argues, often function as vehicles where privilege gets “multiplied by privilege.”

I was honored to organize a team of colleagues to facilitate a candid conversation among museum professionals, educators, students, activists and thought leaders from the DC metro area and near-surrounding regions about the state of internships. Seventeen museum professionals joined us in the Alliance’s offices in Arlington, Virginia for a local and intimate half-day dialogue. The convening focused on the topic of museums and internships and was designed to explore the kinds of questions about privilege and equity that Walker’s article raises. CFM’s founding director Elizabeth Merritt moderated the convening with exceptional skill and thoughtfulness. AAM’s President and CEO Laura Lott gave opening remarks and also helped foster a spirit of openness and dialogue throughout the meeting.

The purpose of the dialogue was neither to reach conclusive resolutions about the topic nor provoke total consensus among the attendees. The issue of museum internships touches our entire field. It involves many moving parts and many, many invested perspectives—it’s an issue far too complex and wide-reaching to be exhaustively unpacked in four hours by a handful of people from one region in the country. (I, for one, am too much of a contrarian to believe that that was even possible to accomplish in a single afternoon.) The purpose of the dialogue was to:

- Identify the stakeholder groups in the internships conversation (e.g. interns, academic departments, emerging professionals, museum leadership)

- Develop language to discuss the implications of internships on diversity, equity, access and inclusion

- Establish the groundwork for further engagement with this issue

I want to share some things I learned from a rich, engaged dialogue on the topic. (I’ll be sharing more of the insights from the convening and next steps on the Blog in the coming months.) Here are some of the key things I learned about how museums can begin the work of discussing the ethical, financial, and labor dimensions of internships

- The Importance of Diverse Perspectives,

- The Importance of Disagreement, and the fact that

- Sometimes the Question Isn’t Really the Question

The Importance of Diverse Perspectives

In putting together the list of invited participants, our team wanted to make sure we assembled a diverse sample of museum professionals. We reached out to interns and people who run internship programs; students and professors; members of Museum Workers Speak; bloggers; leaders of regional and national museum organizations; and emerging professionals. The participants in attendance were:

- Diane Barber, Development Assistant, Ford’s Theatre Society

- Karen Daly, Executive Director, Dumbarton House

- Omar Eaton-Martinez, Program Manager, Smithsonian National Museum of American History

- Amanda Figueroa, Co-founder, Brown Girls Museum Blog

- Brittany Fiocca, Curatorial Intern, Phillips Collection

- Teresa Martinez, Manager, The Octagon

- Alli Hartley, Coordinator, Smithsonian Nat’l Museum of African Art

- Judith Landau, Museum Studies, Johns Hopkins University

- Kym Rice, Director, Chair, Museum Studies, George Washington University

- Ravon Ruffin, Brown Girls Museum Blog

- Mattie Schloetzer, Program Administrator, Nat’l Gallery of Art

- Kristen Sheldon, Volunteer Manager, The National Building Museum

- Carol Stapp, Dir., Museum Ed. Program, George Washington University

- Jennifer Thomas, Director, Virginia Association of Museums

- Emily Weeks, Contractor, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

- John Wetenhall, George Washington Univ. Museum and Textile Museum; AAM Board Member

- Eric Woodard, Dir., Office of Fellowships and Internships, Smithsonian

Many, many thanks and much heartfelt appreciation to each of the participants for their time, their candor, and their willingness to share!

With such a range of positions represented, we wanted to make sure that we, as the conveners, were upfront about the potential challenges related to the power dynamics in the room. Although we couldn’t guarantee that everyone would reach consensus, we could–and did–take steps to acknowledge the breadth of attendees’ professional experience. In their opening remarks, both Laura Lott and Elizabeth Merritt reiterated the importance of empathy and listening. Elizabeth, as moderator, was deeply attentive to how long speakers held the floor and ensured that people got a chance to reflect and connect with one another.

Prior to the day of the meeting, we established guidelines about creating a safe space for the dialogue to occur. We shared these ground rules with participants before and during the meeting. We asked participants to:

- Practice active listening and ask questions as any time

- Remain fully present by resisting social media and texting during the event

- Not attribute specific quotes to specific people in their social media sharing following the meeting

Our team allotted the bulk of the time for laying out the issues to make space for just that. Participants spent some 90 minutes thinking through how museums should define internships, reviewing the Department of Labor’s Guidelines, and identifying ethical and financial dimensions of the internship process. There were moments of intense debate. For instance, a discussion of the distinctions between jobs and internships opened up into a broader discussion about the perceived stigma of taking a job outside of the museum field. Several participants shared stories about feeling marginalized because they’d chosen paid work in other sectors over unpaid work in museums at earlier moments in their careers. Although I’d been thinking about the economics of museum work—and unpaid internships especially—I had never considered how paid employment outside of the field could be a target for unconscious bias for some employers. And I wasn’t the only one for whom this was a revelation. Having a multiplicity of voices at the table (literally) created space for un-told stories about the realities of museum labor.

The Importance of Disagreement

The process of assessing and improving the state of museum internships requires vulnerability, flexibility, and dialogue. Official definitions of what constitutes an internship resist permanence. Even the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) has had to revise their criteria for what constitutes a legal internship, and the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) has offered recommended revisions of that criteria. Some attendees agreed with the definition of an internship as a “guided learning opportunity” with a more didactic function. Others preferred to think of this guided learning as experience-based. Still, others disagreed with this definition altogether, preferring to define internships as “professional training” over the popular university-based model.

Opinions also varied around the language of compensation. Some in attendance preferred “stipend” and “scholarship” to the term “salary.” Others asked probing questions about the value of these labels. Importantly, participants raised the question, “What does each tell us, really?” Some participants voiced concerns that the use of terms like “stipend” and “scholarship” are used to obscure when an internship functions more like an entry-level job, with the result that entry-level jobs in the field actually become jobs that require a good deal more experience and education than is signaled by the term “entry-level.”

There was no universal agreement on any of these definitions and criteria beyond the understanding that internships should be “for the benefit of the intern.” But, inside of this discussion, participants suggested several powerful changes to current practices. Attendees asked:

- Can the field move towards an alternative credentialing model that bypasses internships altogether?

- Are apprenticeships a possibility?

- Can internships be administered through museums’ education departments instead of through HR managers?

Another lightbulb moment included the suggestion that small museums could share HR staff (which participants dubbed “HR shares”) in order to help make the process of administering internships much more even and transparent. These suggestions resulted not from consensus, but from respectful back-and-forth about the issues. The very act of engaging internship practices invites an opportunity to envision future alternatives.

Sometimes the Question Isn’t Really the Question

The conversation regularly flowed from internships into a larger dialogue about the viability of the field. Participants were deeply interested in addressing the whole environment of museums’ needs around internships. This includes retention, the economy of museums, financial sustainability of museums, and the need to begin the pipeline to museum employment much earlier. Internships operate in a wider museum environment and their equitable application has implications beyond any individual museum’s specific operation. Addressing internships alone will not, in fact, completely get us toward a larger vision of diversity, access, equity, and inclusion. Better retention programs, increased cultural competencies, and re-thinking of the criteria for employment credentialing (e.g. the cost of museum studies programs) all came up in conversation as suggested: “better practices” for the field. Recommended steps that moved beyond the purview of the internship included:

- Museum studies programs’ offering career counseling to students about the economics of museum work

- Museum professionals—and our organizations—sharing information about the specifics of contract labor, including taxes

- Increased collaboration with related federal initiatives for professional development and youth programming

- The production of a field-wide tool that helps students evaluate what programs are best for them.

In reflecting on these suggestions, it becomes clear to me that, ultimately, the vision for success in addressing museums and internships is linked to a larger vision of sustainability and increased access to the field. The problems of privilege that cause bottlenecks in the pipeline to museum employment require coordinated interventions that both include and exceed the form of the internship itself. The issue of museums and internships is future-facing—a subject that benefits from our creative, disruptive, and sometimes-contradictory efforts. Together.

What questions would you add to a dialogue on museums and internships? Have you or your museum held similar conversations? If so, what’s worked and what hasn’t? I’d love to hear from you at nivy@aam-us.org.

Thanks for this post. There was an interesting discussion on this issue a few years ago on Nina Simon's blog – worth a read, especially the comments that showed this was (& still is) a hot topic: http://museumtwo.blogspot.com.au/2013/12/guest-post-shared-ethics-for-museum.html

Thanks, Lynda, for the reference! I've used Simon's post to guide my thinking a lot–especially the links she makes between unpaid work and the pay scale. "If the lowest wage on the ladder is zero," she writes, "entry-level wages don't have to be much higher, and this affects the whole pay scale for the majority of those who work in non-director positions." This came up during the conversation, too, as several attendees raised concerns about the potential of unpaid internships to heighten the qualifications required for entry-level positions while depressing the wages offered in these appointments.

We just ran a survey of museums in the United States and Europe and found that 53% of museum interns receive no pay for their work. The full survey can be found on: https://www.museumnext.com/2017/07/stats-on-museum-internships