The theme of the Virtual Annual Meeting—Radical Reimagining—was already poignant in the context of the field’s reckoning with the impacts of COVID-19, but became even more so in the midst of nationwide protests against police brutality and systemic racism. In the spirit of reimagining a better future for museums and the communities they serve, EdCom’s Trends Committee below presents a few key takeaways for museum education emerging from conversations that took place throughout the meeting.

We must fulfill our role as a trusted resource.

During a special session in response to the protests, Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch III suggested that museums “cannot be community centers…but they sure could be at the center of their community.” This is especially important as we try to meet the needs surrounding COVID-19 for our community, which we must do through open, clear communication. As Drs. Sharfstein and Watson from Johns Hopkins University presented in a briefing during the meeting, it is incumbent upon museums to use our platforms and presence to amplify voices of expertise and ensure correct information on public health practices is being received by the community.

Educators have the opportunity to facilitate learning from experts to our community. Our ability to share content and reach the diverse levels of learners will help clear misconceptions surrounding the virus and promote ways to stay healthy and safe during this time. Hosting virtual discussions featuring local public health experts or leaders to promote health and wellness in the home will provide access to people who might not be able to receive these messages otherwise through traditional mass media outlets. Museums that have hosted such experiences have not only helped get the message out, but also allowed for the community to have their questions and needs addressed in real time. These messages aren’t just important for science institutions to share out; museum education in all disciplines can and should adapt to the moment by pairing relevant collections, artwork, and stories with the messages of local experts.

As we prepare to reopen, museums also need to create a safe, welcoming environment for guests and staff to return to the museum floor. Where can education on safe handwashing and distancing be included in your museum experience? Using digital presentations and discussions in the days and weeks leading to reopening, we can prepare people for what their new visiting experience will look and feel like, educate them and ourselves on what is most important for on-site experiences, and emphasize how we will keep each other safe.

We need to balance quick responses with long-term planning.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleWhile museums’ tendency toward long-term planning can offer much-needed clarity in times of crisis, the pandemic and recent civil upheavals have proved that communities’ needs often change much more rapidly than a museum’s strategic plan allows. In her general session address at the beginning of the conference, Christy Coleman of the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation called for responsive museum programming, and many of the case studies offered throughout the week reiterated its importance. AAM embodied this mindset with the addition of Dr. Johnnetta Betsch Cole, Lonnie G. Bunch III, and Lori Fogarty’s panel to the program, which was added as a way to “help process the weight of the current moment.” Whether it’s creating a digital “care package” to serve a community who is newly in crisis, as done by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, or entering a community partnership without any kind of preset agenda, museums have begun to model a responsive approach to serving their community and must continue to do so.

To shorten your planning process for programs, perhaps you could start explicitly “workshopping” the structure with participants as a way to gather feedback for continuing or adjusting the program. To borrow from the tech world, these programs could be seen as “beta” initiatives that are designed to listen to community feedback. For this process to be meaningful, however, the feedback must be intentionally integrated into programming or operations in visible and concrete ways.

In other cases, shortening timelines means handing over authority to community partners who already have the “know-how” to execute certain parts of the project. These kinds of partnerships can expedite the process. The museum, in turn, must learn to relinquish control and be comfortable simply offering the assets of space, time, or money. A concrete example of this during COVID-19 can be seen in the institutions and individuals that are creating art kits but then partnering with organizations like homeless shelters and food banks to distribute them. There is a letting go in that process which leaves room for other organizations and communities to contribute in meaningful ways, while greatly increasing the impact and speed of a project.

Now is the time for all museums to reorient with a community focus.

In the field and outside of it, many are collectively pausing to reflect on museums’ roles in society and their exclusionary histories. As we reflect on what role we want museums to serve in society, the time is now urgent for all museums to truly reorient to respond to community needs and prove their worth. As Devon Akmon, former director of the National Arab American Museum and current director of Science Gallery Detroit, put it during the Annual Meeting, it is simply not possible to have rapid programming that is responsive to real-time community needs without having a well-established relationship with the community to serve as partners in meeting the moment.

What changes need to be made at an institutional, departmental, and staff level for your museum to live at the center of your community? For example, you might reserve space at your institution to be always “open” for rapid response programming that may arise. Alternatively, you might put long-standing projects on hold and instead highlight the work of peer institutions in your community that better serve the needs of the moment. One recent rapid response example from the field comes from the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, which has pivoted to collect stories of resilience from members of the Anacostia community in the face of nationwide protests against systemic racism.

Let go of the sole creator role—help those outside the staff be authors.

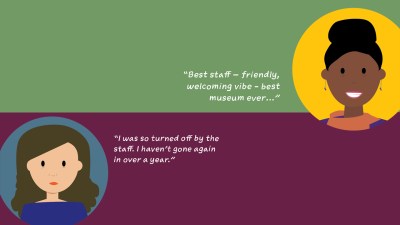

While this idea is not new, the role of the sole creator and the so-called “professional” voice still dominates in museums, creating an atmosphere of authority. Opening our doors and sharing authority not only makes us more relevant, but it creates a truly engaging and participatory experience. However, we need to be sincere and mindful when we invite external creation and participation. If we are not genuine and do not listen, we run the risk of alienating our audiences and exhibiting tokenism.

As educators, we have many opportunities to involve the public to participate, collaborate and co-create content at our museums. Science museums are having a lot of success with citizen science projects; for example, the Museum of Life Science in Durham, North Carolina, runs a series of “Experimonths,” where visitors help collect scientific data. At the AGO Art Gallery in Ontario, the exhibition In Your Face featured a “People’s Portrait Project,” where portraits were collected from the general public to show the individuality and diversity in Canada. Only when audiences feel involved in the museum’s mission can they become invaluable community assets.

Lead by example: invest money to create change.

Recent months and weeks have highlighted the need for change, perhaps more than ever before. It is therefore time to reassess our mission and offerings, so that we can not only put our money where our mouth is, but be a real agent for change. It is important that museums look internally at operations and purchasing as well as at external programming and outreach.

Museum educators have a great opportunity to effect change in examining their own budgets for community investment, from where supplies come from to where contracts are going. Are you ordering supplies from Amazon, or from local sources? Do the individuals your institution is initiating contracts with (for educators or media producers, for example) reflect the demographics of the community you wish to serve? Another example for change can come from your internship structure—eliminating unpaid internships as a measure to establish a more level playing field for potential candidates. Finally, not only do we need to focus on where to invest our resources, but we also need to look very carefully at our funding sources to make sure that they align ethically and morally with our institutions’ missions and values.

Being future-minded and hopeful may be the key to making museums essential in the eyes of the public.

With many museums closed to the public or significantly altered in their programming and visitor experiences, all are wondering and reassessing: What is the true value of museums, and what is their future? While most museums, either by virtue of mission or collection, have historically given focus to the past, a radical next step might instead be to become places where better futures are imagined, as Marina Gorbis posed in her address.

Setting goals for programming that center on hope could revitalize visitors’ perceptions of museums and change our expectations for what core competencies educators bring to the table. For example, for an exhibit focusing on the civil rights era, one might develop a goal that prioritizes visitors feeling more empowered to organize as a community and to communicate with elected officials the changes they wish to see in their communities. In this future-oriented model, attitudes would become more important assessments of impact than knowledge and understanding.

Comments