To continue providing meaningful experiences for pre-K through twelfth-grade audiences in the era of COVID-19, museums must re-envision educational practice for the virtual realm. By sharing about a pre-COVID virtual education program I was involved in, I hope to illustrate how such programs can captivate student audiences through cross-cultural connections and school-museum partnerships, while broadening our collective imagination for virtual learning.

This program was a collaboration between Christina Petrides, a first-grade educator at Mount Royal Elementary Middle School in Baltimore, Maryland; Valerie Clark, PhD, Field Research Scientist and Executive Director of the Indigenous Forest Research Organization for Global Sustainability (iFrogs) nonprofit organization; and myself and colleague Iman Cuffie, museum educators at The Walters Art Museum.

Together we facilitated a virtual STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Math) program that orchestrated live video exchanges between first-grade students in a Baltimore City Public School classroom and students in a remote fishing village near Lokobe National Park, Nosy Be, an island off the northwest coast of Madagascar.

We collaborated to develop a four-part program, outlined below:

Part 1. Museum Educator Classroom Visit at Mount Royal Elementary School in Baltimore

Iman and I began with a visit to Ms. Petrides’ class in Baltimore, where we introduced students to Madagascar using maps and images from my own journey there while working with ExplorerHome and Tsiory Andrianavalona, PhD.

We explained how Dr. Clark provided sportive lemurs (Lepilemur tymerlachsoni) with manmade wooden resting boxes in the Nosy Be forest, where tree-hole sleeping sites are in short supply due to deforestation. With her local Malagasy team, over fifty boxes were installed for the lemurs, and dozens of lemurs sleep in these boxes all day long, active only at night.

I mentioned that Iman and I would visit their classroom again to facilitate a coloring party with Dr. Clark’s students in Nosy Be, but first we would prepare for that experience by visiting The Walters to see animals in art.

In preparation for their museum visit, we viewed an image of an ancient Egyptian baboon mummy coffin. We discussed what type of animal it represents and in what habitat that animal might live. We also discussed how the object was made and what materials it is made of. One student was able to describe how it was used to hold mummified baboon remains in ancient Egypt.

We also observed the Temple Relief of Nectanebo II.

Within this ancient Egyptian cultural object are hieroglyphs that depict animals. As we discussed animal symbolism, many students were able to identify the writing system and began to enthusiastically anticipate their field trip.

Part 2. Mount Royal Elementary School Field Trip to The Walters Art Museum

Upon arriving, the students walked into the sculpture court at The Walters, where they could barely contain their excitement. Their enthusiasm was contagious!

The Mount Royal students participated in guided tours of art depicting animals led by docent volunteers. Afterward, I facilitated a studio art-making experience where they created creature combinations and habitats using collage materials.

I filmed portions of their museum visit to share with Dr. Clark and her students in Nosy Be. The Malagasy students lit up as they virtually visited the museum with their new school friends. We were all very excited for the next phase of our collaboration.

Part 3. Coloring Party and Live-Video Exchange between Mount Royal Elementary Students in Baltimore, Maryland, USA and Students in Nosy Be, Madagascar

Iman and I visited Ms. Petrides’ class again for what was sure to be an exciting day. It was our first live-video exchange between students in Baltimore and Nosy Be! We began by reviewing the content we discussed previously. Then Ms. Petrides showed them an iMax documentary starring iFrogs Vice President Dr. Patricia C. Wright, Island of Lemurs: Madagascar, where students learned more about Malagasy primates like the mouse lemur and the indri. After watching, they excitedly shared what they learned.

I explained that the students in Nosy Be speak French and a dialect of Malagasy called Sakalava. We all practiced saying Mbola tsara (mm-BOOL-uh TSAR-uh), a Malagasy greeting. Before we knew it, we were live on Facebook Messenger! Iman and I worked with Ms. Petrides to set up a laptop, projector, and webcam so we could receive the call and project the image for the Mount Royal students. Dr. Clark and her eleven students used her smartphone to connect with us, where they could see and hear the class through the webcam as they gathered around her phone.

The Mount Royal students greeted their new friends with an enthusiastic, “Mbola tsara!” The students were visibly excited to see each other. Iman heard one Mount Royal student observe, “the (Malagasy) students look like us; they look like they could be in Baltimore.” The students in Madagascar, in turn, were surprised that American children represented a variety of ethnicities. The children appeared to immediately accept and love sharing with one another across ten thousand miles.

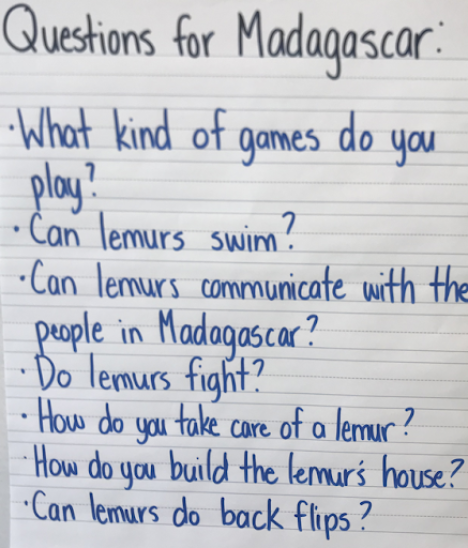

Ms. Petrides worked with her class prior to the coloring party to develop questions to ask Dr. Clark and her students. As they asked their questions, Dr. Clark translated the responses so both student groups could follow the discussion.

With some rapid translation, the children discovered they loved doing similar things, like playing sports, especially with balls, and coloring. They were noticing commonalities while witnessing how others live in cultures different from their own: “Wow, they are on the beach!”

After the discussion, we began our coloring party with the sportive lemur coloring sheet.

Embarking on this activity with students in Nosy Be through a live-video exchange created an atmosphere of excited curiosity. From Baltimore, we could observe Nosy Be students, their work, their outdoor classroom, the shoreline, and the Indian Ocean. Similarly, the Nosy Be students could observe Mount Royal students, their work, different technology, and an American classroom like the one their teacher Dr. Clark came from. Both groups gained glimpses of the everyday surroundings of their new friends.

Upon finishing the lemur coloring sheet, we began coloring the squirrel page and discussed their similarities and differences, stressing that lemurs have hands and fingernails, like all primates.

We experienced how connecting students from across the world increases global and cultural understanding, through personal connections that will likely not be forgotten. For Dr. Clark, it was particularly moving. “I’ve been working in the same village, Antafondro, since 2008, and love my adopted family there, including many children I’ve held as babies who now participate in my environmental education programs. The Malagasy children had already learned quite a bit about me and the United States, so to meet students their own age who grew up in Maryland, USA, where I came from, and seeing how similar we all are was beyond magical. I am so thankful to the staff at Mount Royal and The Walters and am keen to share this experience from Madagascar with other classrooms in the USA.”

Part 4. Virtual Backyard Forest Hike and Live-Video Exchange between Mount Royal Elementary School Students in Baltimore and Students in Nosy Be

In the last part of the program, Iman and I visited Ms. Petrides’ class to facilitate our final live-video exchange. Dr. Clark and her students planned to take us on a virtual forest hike in Nosy Be. To prepare the Mount Royal students for this, Iman and I asked them to recall our previous conversations. I debuted a video of their visit to The Walters while explaining that Dr. Clark had showed this to her students in Nosy Be. Then we heard the chime. Our friends in Nosy Be were calling! The students were happy to reconnect.

We began our virtual hike to visit lemur resting boxes with Dr. Clark and her students.

We observed how staff at iFrogs climb trees to check the resting boxes.

And we saw the lemurs! As Dr. Clark narrated for us in English and her local classroom in French and Sakalava languages, we learned that we were looking at a sportive lemur named Ylang-ylang and her month-old baby.

We also saw a sportive lemur named Mango and her infant.

They were not in their resting box when we saw them, but in a nearby tree where we could observe them climbing. What luck! According to photographic data from Dr. Clark’s Malagasy field team, Mango and her baby were in their usual resting box in the weeks and months after.

We were also fortunate to hear and see black lemurs (Eulemur macaco) as they climbed through the trees. While the Malagasy students continued their hike in the Nosy Be forest, the children and lemurs called to one another, answering a question from the Mount Royal students about lemur communication.

Next, we were introduced to Leela, the one-eyed sportive lemur, with her baby in another resting box. “We don’t know how Leela lost her eye, but she is very healthy and for the past two years we have monitored her, she lived in the boxes most of the time and had a healthy baby each year,” explained Dr. Clark.

Iman and I facilitated discussion among the Mount Royal students as they watched. In preparation for the exchange, Dr. Clark sent me photographs of the lemurs we might see. I walked around with these high-quality images to give students a closeup view as we saw the live footage. The students witnessed Dr. Clark and her team facilitate a lemur capture, a weighing demonstration, and a release. Each exchange sparked visible excitement and curiosity among all involved. Learn more about iFrogs by following Dr. Clark’s work.

Facilitating these exchanges within a school-museum partnership offers learners a variety of pathways towards engagement. It can nurture interest and curiosity through inquiry that engages the foundational knowledge learned through in-school instruction. To embark on a cross-cultural collaboration of your own, begin by assessing your networks. Who do you already know that may be a good partner for a project like this? Cross-cultural exchange can include international collaborators, but they can also be just as meaningful at national and local levels. Consider connecting with existing educator networks on social media platforms to put a “call out” and learn who may be interested. Programs like the National Geographic Educator Certification will connect you with a global network of educators and resources to expound upon collaborations. Also, check out National Geographic’s Explorer Directory and connect with professionals on LinkedIn and social media who may be interested in supporting this work. If you don’t have the capacity to build your own network, consider the Out of Eden Learn program, an initiative of Project Zero. This program provides the structure, framework, and connections to support classroom cross-cultural exchange initiatives.

There are many student, educator, and institutional benefits to education models that incorporate cross-cultural exchange. These opportunities can build a broader and more personal understanding of human communities around the world, including one’s own. Co-creating these experiences within a school-museum partnership provides an exciting space to experiment while re-envisioning museum practice, in the era of COVID-19 and beyond.

About the author:

Susan Dorsey works as a museum educator at The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, where she combines her art and science backgrounds as a means of storytelling and builds partnerships to create innovative, interdisciplinary curricula. Because of her unique contributions to the field, Susan received the 2019 Eastern Region Museum Education Art Educator Award, and the 2017 Maryland Art Museum Educator of the Year Award. Susan graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Maryland Institute College of Art and a Masters in Biology from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio in the Global Field Program. She would like to thank Keondra Prier for her guidance, support, and advocacy for this program, and Frank Dickerson for his technological expertise.

Valerie C. Clark, PhD is a National Geographic Explorer and co-founder of iFrogs 501(c)(3) nonprofit based in Florida, USA. She has designed and led environmental outreach and conservation activities in Madagascar since its foundation in 2012, including the lemur nesting box project that is helping a critically endangered lemur to bounce back from the brink of extinction. Thanks to employees and friends born in Nosy Be, we remain in constant contact throughout the pandemic—please reach out to request a program for your classroom to visit the lemurs in Madagascar with iFrogs team: Clark.iFrogs@gmail.com. She would like to thank Professor Patricia C. Wright, PhD, for consulting on this program and Martin County High School (Stuart, Florida, USA) Fine Arts teacher Mrs. Amanda Jones for creating the coloring sheets from Dr. Clark’s photographs and related volunteer consulting.