You may know that Old Salem Museums & Gardens (OSMG) and The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, have been making considerable changes over the past four years. What you may not know is the context fueling and driving these changes. It is a complicated story, which I want to tell in this essay in an open and fiscally transparent manner.

My goal in writing this synopsis of our analysis, processes, and results is to empower other historic sites to address their particular issues directly and thoughtfully. Merely tweaking a system that is out-of-date and dysfunctional will inevitably fail. From the outset, I suspect, one must anticipate ending up with something entirely different from that which came before. That possibility is the new normal.

First, I will candidly outline, using financial data, the situation that Old Salem has operated within since the Great Recession of 2007, and even before. Next, I will discuss how we collected data and conducted our analysis of that situation. Then, I will present some of the initiatives we created to counter the institutional deficiencies we discovered in that process. Finally, I will discuss some of the results in finances, feedback, attendance, and revenue.

Assessing the Situation

Old Salem Museums & Gardens, which includes the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, ended the 2007 budget year with 242 employees, an operating budget of $7.6 million, and a $1.56 million deficit. This deficit continued for the following decade, forcing the organization to operate in the red, with a total accumulated deficit of close to $6 million. In attempting to maintain the same operational model under this deficit, the organization drew heavily from its board-restricted endowments, averaging about a 10.75 percent draw on selected endowment accounts, with some endowment draws as high as 25 percent.

The board of trustees and staff responded by cutting operational expenses while also attempting to “prop up” the museum’s existing visitor experience, a 1950s historic house museum model of “stepping back in time” through costumed interpreters enacting tableaus in chained-off period rooms. This decision resulted in an institutionally crippling scenario. By sticking to the same traditional and labor-intensive model, while not having the financial resources to sustain it, Old Salem was on a path to insolvency. In addition, our attendance, as with most other history sites, had been in steady decline for over two decades. At one time, Old Salem had about one hundred thousand paid visitors annually; by 2016 that number had dropped to approximately sixty-five thousand. Fewer visitors meant less earned revenue from tickets, which meant less money to pay for the same outdated visitor experience. It had become clear that the organization could not continue with business as usual if it wanted to survive.

In response to these factors, the board of trustees and former CEOs Lee French and Ragan Folan led a continuous effort focused on fiscal stewardship. However, by 2015, despite a 22 percent drop in staff size, the operating budget had grown to around $8.4 million. It became clear that the organizational maladies were not merely financial; a profound reconsideration of the core museum experience was needed. In the fall of 2016, the board of trustees, acknowledging this need for in-depth reassessment, asked me to collaborate with them on transforming the site’s operations as President/CEO. I should note that in hiring me, the board wholeheartedly agreed to the process of change. Without this level of commitment, the ensuing experimentation would have been impossible.

Reshaping the Organization

With this assistance and approval from the board of trustees, we began in January 2017 to make structural changes to the way OSMG/MESDA operated. We reconsidered everything. Our first moves were a series of very significant changes that laid the groundwork for our later experiments and cultivated resilience.

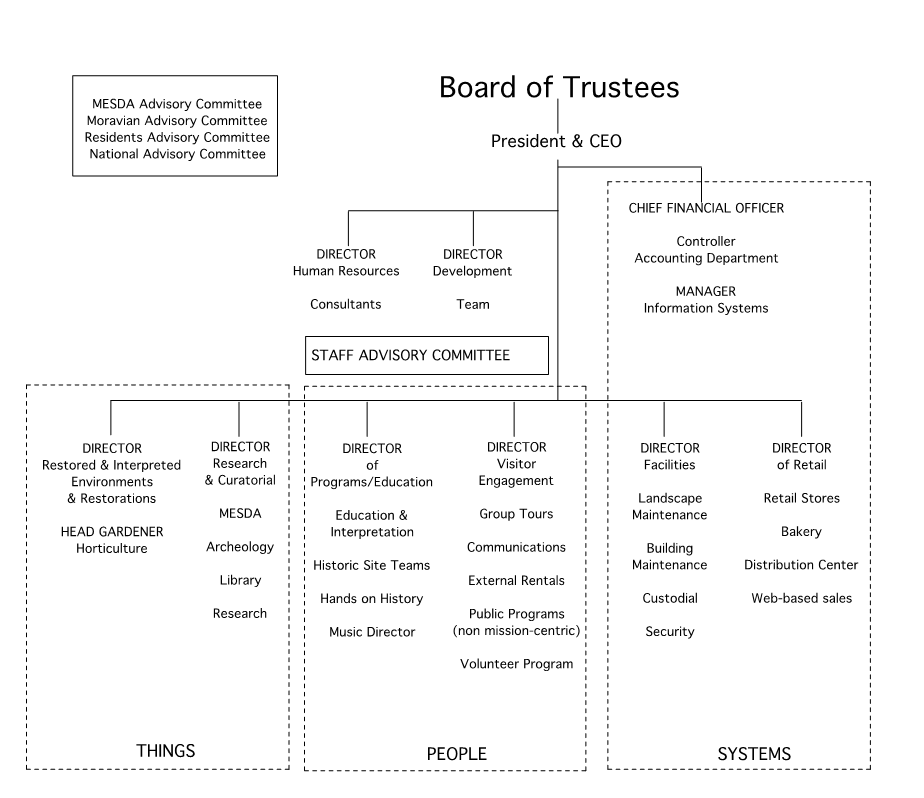

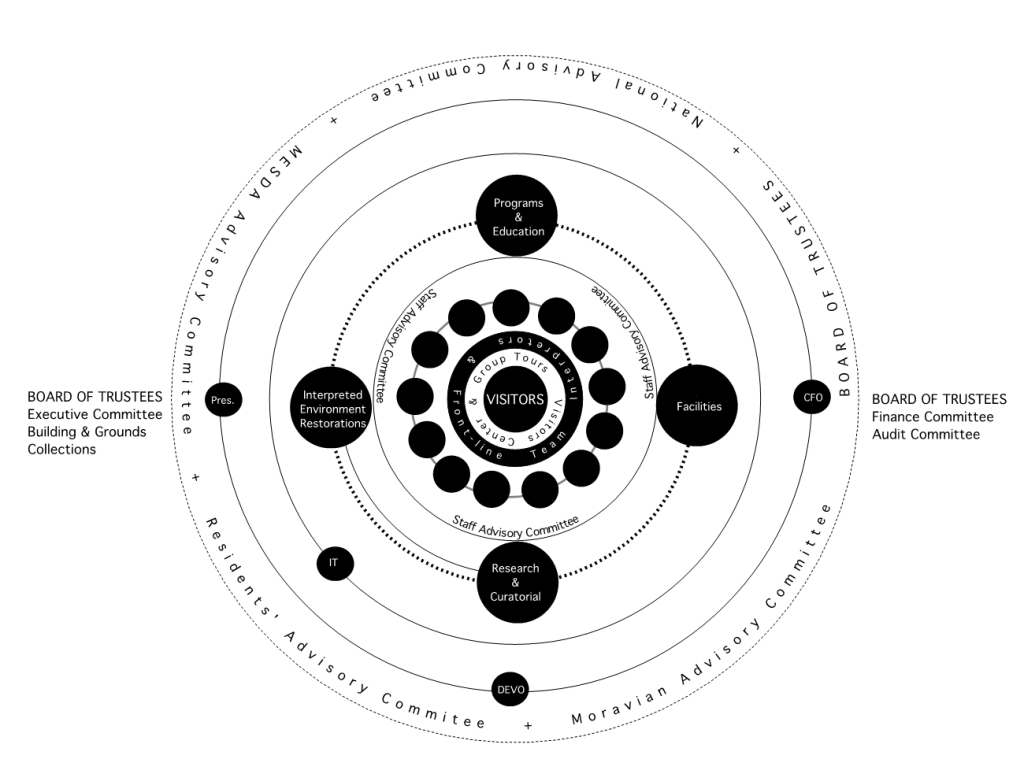

First, we transformed the executive leadership team, expanding it from a group of four to a group of twenty and rebranding it as simply the “leadership team.” This new leadership team represents every division in the organization and is vastly more diverse in terms of gender, race, and economic status. Unlike traditional management bodies, whose membership is made up entirely of executive-level leadership with executive-level salaries, the average salary of this group is between fifty and sixty thousand dollars. The team meets weekly, usually for about an hour, during which all members update the entire group on their respective activities. This has produced unprecedented levels of collaboration and oversight. By broadening the definition of leadership and giving voice to a more inclusive cross-section of our organization, we have removed the barriers between divisions and begun to share responsibility broadly as a unified management team.

Next, we inverted the traditional hierarchical organization chart, re-envisioning operational functions to place front-line staff and visitors at the center of everything we do. We flattened the top-down leadership by reducing the distance between the CEO, COO, Senior Development Director, Chief Curator, and front-line staff. We grouped previously siloed tasks into three categories: Things, People, and Systems. But these changes were not dictated from the top down and they are not etched in stone. In fact, we have gone through more than a dozen versions of this org chart so far as we have proceeded with our experiments and restructuring.

These philosophical changes about the role of management are most visible on a “high-volume day,” when we have somewhere between three hundred and one thousand visitors in the historic district. Unlike most medium-to-large organizations like ours, which have an entire class of employee who never interacts with the public, we now have a mandatory responsibility embedded within all job descriptions that on such days all employees, no matter what position they fill, must wear period-appropriate clothing (or modern clothing with an Old Salem “Ask Me a Question” apron) and get out on Main Street to greet our guests. This has removed the classic divide between “front-line” staff and management faced by so many sites. It provides our entire team with a front-line view of our audience, and it promotes creativity and collaborative problem solving across all levels of the organization. Even as CEO, I became a regular “street cleaner” who put on historical clothing, grabbed a handmade broom, and spent the morning sweeping the sidewalks from one end of the historic district to the other, using this time to talk with and learn from our visitors. And I asked the rest of our team to do the same; to find out what was working, what was a problem, and consider how could we fix it. Many of these conversations informed our new initiatives that I describe below in this article.

Conducting an Analysis

With these structural changes in place, the immediate priority became to collect detailed data about the organization and its programming, then conduct a thorough analysis of that data. We needed to diagnose the problems, tease them apart, and address them head-on one by one. This was the mandate the board of directors gave me. The core goal was to maintain and highlight what has always been important at OSMG/MESDA and re-consider things that were obscuring that core seed.

Using our new leadership model, we were able to quickly analyze national and international museum trends in comparison to Old-Salem-specific trends, placing our problems in a broader context for the board of trustees and staff to work from. We were not alone, we learned. This exercise began a culture of outward-looking dialogue and innovation focused on promoting those things that made us unique.

We concluded that we had two primary problems:

- Our organizational footprint (physical as well as programmatic) was too large for the size of our endowment, development, and other revenue streams. With more than one hundred acres of interpreted landscapes and gardens, more than ninety historic buildings, multiple collections facilities, a decorative arts museum, and an outdated interpretive model, we would never “catch up.” We just didn’t have the resources.

- Our visitor experience (for both school groups and walk-in visitors) did not satisfy contemporary expectations, so we were losing attendance, volunteers, and interest. While non-ticket-buying visitors to the historic district had increased, we were down 38 percent in school tours since the 1980s. The typical historic house museum tour—with chained-off rooms and detached, non-tactile interpretation—was out of date and needed a dramatic change in order to support the curricula and learning objectives that teachers and students rely on, a core part of our mission.

The next step in our self-analysis was a complete organizational program assessment. Starting in Fall 2017, we created an organizational-wide program budget datasheet that we used to assess every program’s costs (including staff costs and overhead) and revenue in a consistent and comparable way. The results were astonishing. More than 60 percent of all programs were losing money and draining resources away from core operational functions. As we investigated further, the data showed that much of the organization’s staff time was dedicated to facilitating programs with no, or very little, financial return. Following this initial assessment, we took the difficult but necessary action of ending long-running programs that were no longer viable. In place of them, we began experimenting with new concepts and events that signaled our understanding of changing cultural needs.

At the same time, we took to the sidewalks of the historic district and city (physically and virtually) and had conversations with visitors and our local Winston-Salem community. We reviewed TripAdvisor comments, held town hall meetings with staff and community members, and began regularly presenting to various community organizations. These crowd-sourced critiques, which fell into similar categories, were fundamental to our re-awakening.

Developing New Strategic Initiatives

After analyzing and discussing this feedback, and agreeing not to shy away from disruptive change, we initiated a series of course-correcting initiatives. These initiatives have helped us to reset our organizational priorities. They have served as commitment markers for the public to see our sincerity in making changes that positively affect things that they felt were valuable—not things we thought they should think were valuable.

Based on the feedback, we began all these new core initiatives in 2017:

Activate Main Street

One of the most common things we heard from our visitors was that the Old Salem experience was stale, limited, and boring. We had eleven ticketed venues spread over a half-mile long historic district, each containing multiple craftspeople and limited activities. This gave visitors the impression that little was open and there was little value to purchasing a ticket to go inside of the buildings. Instead, people were choosing to simply walk the streets for free.

To address this issue, we developed Activate Main Street, an initiative designed to reinvigorate the environment of the historic district and the visitor experience. Activate Main Street had three main components:

- We removed the barriers in our historic spaces, making them 100 percent immersive and tactile, with meaningful experiences for all ages.

- We moved many of our behind-the-scenes activities into public-facing labs within the historic district (research, archaeology, horticulture & seed saving—and soon, an architectural preservation lab).

- We greatly expanded our basic signage, including a new crowd-sourced visitor map, new informal wayfinding, and added seating all along Main Street.

Hidden Town Project

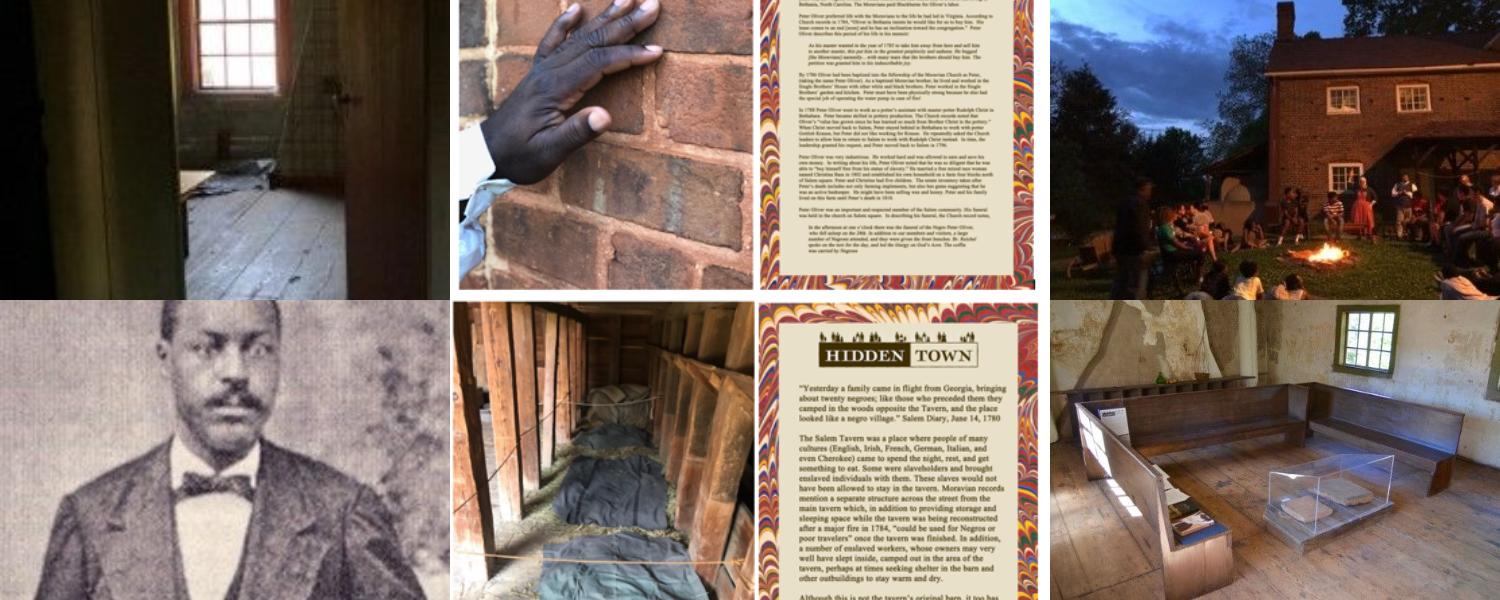

Many of our visitors told us they felt like the traditional narrative of the site, focused on European settlers from the Moravian Church, was too narrow, and that it seemed like we were “hiding something.” Many members of the local Black community, for instance, had never visited the site because they considered it a “white history site.” While Old Salem did have dedicated venues that discussed the history of the enslaved in the town of Salem, they were on the edge of the historic district and were easy to miss. In effect, our story was largely centered on the white Moravian residents and enslavers. We gave little information about those who were themselves enslaved, although the documentary evidence that would allow us to do so was easily accessible.

In answer to this critique, we introduced the Hidden Town Project to research and reveal the history of enslaved and free people of African descent who once lived in Salem. First came the research: In our initial findings, we learned that there were about 160 enslaved persons in Salem and at least forty distinct slave dwellings throughout the town. But then came the more challenging part: figuring out how to incorporate this research fully into all that we do. To that end, findings from the project:

- Are shared throughout the historic district with new venues, text boxes, and biographies of enslaved individuals, both online and at the places where they lived.

- Inform new public programs, often with local and national partners like the Slave Dwelling Project and Chronicles of Adam.

- Inspired the formation of a Moravian Advisory Committee, with an eventual descendant community advisory team.

Led to the creation of the “Hidden Town Project Room of Reflection” in the historic tavern, where visitors can silently reflect on the lived experiences of the enslaved in the heart of the historic district.

Access Salem

Many of our visitors told us Old Salem was physically inaccessible, and that we prioritized pristine preserved buildings and landscapes over access and the visitor experience. In response, we developed Access Salem, an initiative dedicated to achieving the highest possible degree of access for all visitors. Our long-term goal is to transform the Old Salem experience into one that profoundly engages visitors no matter their physical or cognitive challenges. To date, we have:

- Introduced a special map for our visitors who need additional help navigating the site, including social stories for those on the autism spectrum.

- Created “exploration boxes” in each historic venue to meet the needs of visitors who need a more private and hands-on experience.

- Formed a community advisory committee.

- Facilitated our first annual “Access Salem Saturday” for our visitors with various disabilities.

Learning in Place

Old Salem’s educational experiences also needed revisiting. With a few exceptions, they followed a 1950s model of field trips as passive, didactic learning sessions, with hands-on experiences offered only at an additional cost. An unengaging experience leaves historic sites especially precarious in the statewide context, where demand for field trips has declined 39 percent over the last ten years, with history no longer a tested core curriculum module. Over the same period, the percentage of Title 1 (disadvantaged) elementary school students in our community has increased from 42 percent to 62 percent.

In response, our newest initiative (officially launched December 2019), called Learning in Place, is designed to deconstruct and transform the traditional model of the living history educational experience. We are accomplishing this by:

- Re-envisioning Old Salem as an educational facility whose historic venues are classrooms.

- Expanding our curriculum-based instruction to deeply engage STEAM topics in education. We will no longer simply ask our visitors to just “step back in time,” but rather use our landscapes, buildings, collections, and people to connect the multiple narratives of our site to the present and to the school curriculum.

- Employing non-costumed educators, who will work side by side with costumed interpreters to more fully engage academic subjects traditionally outside of the living history experience.

We have also fully integrated our Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts into our educational efforts aimed at families and school-aged children, after realizing they were generally avoiding it despite a radical transformation of its visitor experience that began in 2007. We created a new orientation process that encouraged students to begin their Old Salem experience at MESDA, where they learn how we use the objects of the past to tell stories that have meaning today. This simple step has more than doubled MESDA’s visitation!

Seeds with Stories

The gardens of Old Salem have often been regarded as places for pretty flowers, not educational opportunities. Visitors did not understand the importance of our horticulture and agriculture in the creation of Old Salem. The Seeds with Stories initiative, therefore, highlights the histories of Old Salem’s historic plant collection and gardens in ways that fully integrate them with the primary public experience. To that end, we:

- Moved all horticulture activities to a public-facing Garden Lab on Main Street, where we highlight seed-saving and our botanical collections.

- Introduced potted plants and flowers from our heirloom plant collections at locations throughout the historic district with signage that provided information about the flowers and plants on display.

- Expanded signature public programs to increase awareness of the efforts of the Horticulture Department.

- Reduced the footprint of cultivated pleasure gardens so that we could concentrate our resources on a few well-visited demonstration gardens, while also re-envisioning the gardens to dovetail with educational activities.

- Expanded the horticulture staff to address their new public-facing status.

Equity Initiative

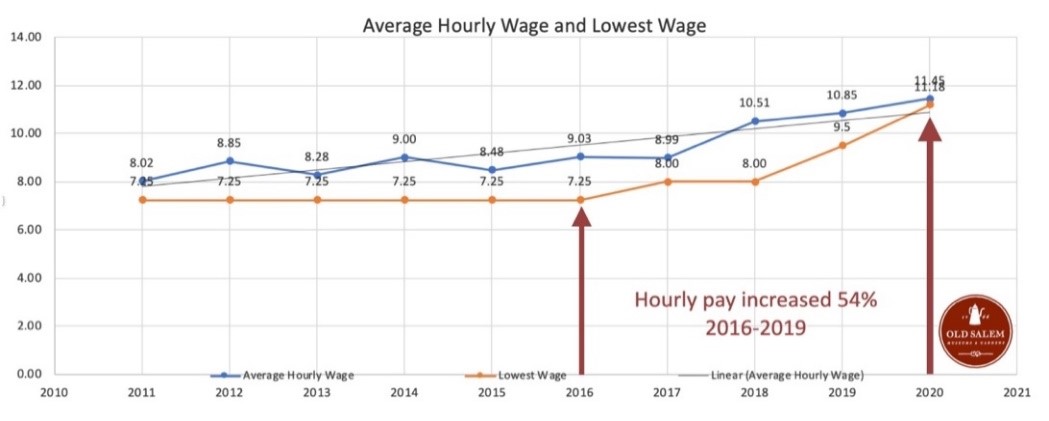

Like almost all historic sites, Old Salem had low-paying jobs (exacerbated in our case by financial difficulties), very little employee involvement in policymaking, and limited diversity in both leadership positions and staff in general. Our Equity Initiative is dedicated to diversity and inclusion in economic status, culture, ability, and race. In short, we seek to reflect the community we serve. Through this initiative, OMSG has:

- Committed to paying above a living wage for Winston-Salem ($10.75 hour), increasing base hourly pay to $11.18 hour (up 54 percent from 2016).

- Facilitated a 1.6 percent cost of living raise for hourly staff—the first time in over a decade that such an allocation was built into the budget—to avoid returning to the kind of wage stagnation we had experienced over the past two decades.

- Expanded our leadership team (as previously described), and established several outside advisory committees, including a National Advisory Committee (representing museum leaders from 17 states), Moravian Advisory Committee, Staff Advisory Committee, Hidden Town Advisory Committee, Cherokee Advisory Committee, Teachers Advisory Committee, and Residents’ Advisory Committee to help inform strategic priorities.

- Increased gender and racial diversity among the board of trustees, with continued movement in this area.

- Expanded our vendor relationships to include historically underutilized POC- and women-owned businesses.

- Reduced CEO/lowest-exempt pay ratio from 7:1 to 4:1.

- Created an HR department to institute organization-wide policies and procedures that ensure non-biased and equitable treatment of all past, present, and future employees.

Clearly, there is much more to do in this area, but the board of trustees has committed to this effort as a fundamental need for the organization.

Salem Check-Up

In the past, Old Salem’s organizational choices and finances were largely managed within a tight executive circle. Few on staff, and fewer in the community, were aware of Old Salem’s financial situation, believing instead that things were okay, when they were not. So, building on the foundation of previous administrations, we launched Salem Check-Up, a three-year resource analysis to better define the organization’s financial and endowment positions, staffing size, programmatic scope, and community engagement. We specifically did this in a candid and outward-facing way, by posting the analysis and quarterly updates on our website.

As our financial situation stands now, the organization is two years away from bringing all endowment draws down to the industry standard of 5 percent yearly. It now operates on less than 50 percent of the endowment income it was drawing fewer than ten years ago. At the same time, our operating budget has been strategically reduced from $8.9 million to $5.9 million.

Re-Envisioning Development and Fundraising

Along with programmatic changes, we have also re-envisioned our development strategy. Before 2017, most fundraising was directed at restoration- and program-specific funding, with smaller-scale fundraising concentrated on event-driven experiences. Like many organizations, we prioritized raising money for large-scale restoration and capital projects, without taking into account the costs to operate them. As a result, we had beautiful buildings but little funding to run them, a combination which left the most important aspects of the visitor experience starved.

We recognized that the only path forward was to focus on significant, unrestricted, multi-year community contributions. Though critically important, these can also be the hardest dollars to raise. However, drawn to our commitment to innovation and our spirit of responsive experimentation, a considerable number of individual donors and corporations jumped in to sustain the transition. At the end of 2019, our development efforts had produced a 19 percent increase over the previous year in unrestricted operations investments. In fact, our focus on multi-year, unrestricted contributions to support the core of our operations has led to the single largest unrestricted grant in the funding history of the organization. Funders understand that change is necessary for the organization to adapt and grow.

Evaluating the Response

At the other end of all these changes, is everyone happy? No. Nostalgia is a powerful emotion. Even with our analysis and the validating subsequent results, I am certain you will find individuals who believe that the last three years of innovation have resulted in the death of Old Salem Museums & Gardens, people who miss the “old” Old Salem. It is difficult for some to appreciate that these old ways of being Old Salem were not working and were not sustainable. On the surface, our circa-2016 experience, with all the free public programs and the traditional interpreted visitor experience, must have appeared wonderfully successful. It certainly felt comfortable to those who remembered visiting the site long ago. But in reality, we have since estimated that for every $27.00 adult admissions ticket, $54.73 was being subsidized by Old Salem to cover the basic cost of providing the traditional visitor experience (real cost of $81.73 per visitor). Schoolchildren paid on average nineteen dollars per ticket, increasing the subsidized amount to $63.73, meaning that we were subsidizing the average forty-five thousand annual schoolchildren visitors to the tune of 2.8 million dollars a year—an amount clearly unsustainable without substantial external donations.

There are also some who feel like we have diminished the Moravian story by expanding the historical narratives we tell to include the lived experiences of enslaved Africans and displaced Indigenous peoples (even though many of Salem’s enslaved were themselves Moravian). I have a file of negative letters and emails to this effect that I keep in my desk. I make it a point to contact every author and speak to them personally (sometimes I even send them a box of our tasty Moravian cookies baked at Winkler Bakery!). Change is difficult, and nostalgia and history are often intermeshed in ways that make change feel very personal. I understand that, and recognize how important it is to allow space for people to be heard.

That said, for all these dissenters there are many more people who have appreciated the transformation and expansion of our historical narratives. Our attendance and revenue tell that story. At the end of 2019, before COVID-19, adult group tour attendance was up 8.3 percent, walk-in attendance was up 2.3 percent, and overall revenue was up 13 percent over the previous year. Our goal has always been to help find a future for our fragile historic site. We want to succeed. The one thing I feel firmly about is this: doing nothing or merely tweaking the status quo means certain death for our history sites.

Another, unexpected benefit of our organizational restructuring has been in positioning Old Salem and MESDA to quickly and collaboratively respond to the negative impacts of COVID-19. Although we are still well into the middle of the pandemic, already we have seen that our transformation has helped us to respond thoughtfully and strategically in this time of crisis. In a forthcoming follow-up to this post, I will share details of how that has been.

Thank you so much for sharing this story. I love Old Salem and applaud your herculean efforts to save this treasure. Back in 2003-4, I worked at SECCA and we partnered with Old Salem to bring the artist Fred Wilson to Winston-Salem. Long story short, this was the beginning, I believe, of taking a serious look at the African-American history in Old Salem. It was life-changing for me, and for those who experienced it. I’m thrilled to see diversity in the stories Old Salem now tells.

@terri – Yes – The Fred Wilson Project, although before my time, was important for Old Salem and MESDA. What we have been doing has been to build onto previous efforts in ways that result in real visitor experience throughout the entire historic district (not just one building)

Dear Franklin,

Thank you for this very insightful read. I would go out on a limb and say many others are in your same boat and what a marvelous transformation you have made to the Museum.

Many of the things you write about ring very true where I work. While some of these same ideals we have adopted, it appears as though we need to do a bit more work.

Thanks for paving a strategic path.

Best,

Erin Dragotto

thanks for sharing this thoughtful map of change. As your principal challenges were reflected in financial weaknesses before the transformation, have these changes resulted in better financial performance? Obviously reducing your budget by 30% must have been painful, but most of what you describe (increasing hort staff, increasing pay) what were the significant reductions in expenditures?

Hi – yes we are in a much better financial position now that before (COVID excluded). We are much leaner and better able to focus our work in ways that utilize and leverage what money we do have.

Our reductions in operations included every aspect of operations. The program analysis really made that clear – our problems were much greater than simply a large staff size.

Thank you so much for sharing this journey. As a museum educator, I find it inspiring and informative, especially your efforts toward access and inclusion. As a North Carolinian (who celebrated a favorite childhood birthday at Old Salem and still gets Moravian cookies shipped to Chicago every year for Christmas), I am excited and proud to hear of its transformation. I can’t wait to visit and see the progress in action when travel is safe.

While I too have fond memories of the “old” Old Salem, having attended Governor’s School in the early 1970s, I also have had the dubious distinction of serving on a museum governing board which was unwilling/ incapable of making the kind of hard choices that you have instituted. Despite a nationally known, landmark collection, the American Textile History Museum in Lowell, Mass., ultimately dissolved and dispersed its assets rather than reinvent itself. The paradigm of “an educational facility whose venues are classrooms” is particularly suitable for industrial museums, and one that I believe is key for the future of every history museum. I’m glad Old Salem is taking the lead in that direction.

I really needed to read this story! I grew up in Forsyth County Schools, going to Old Salem’s Candle tea every year–I love Old Salem. Several years back I purchased ticks for my children/grandchildren to come to Old Salem at Christmas time. I was shocked they were disappointed in the experience. I know you have to change with the times, and I am very pleased you have made the necessary changes! I am also pleased to see your foresight to moving to “stay alive” for the future!

Ann Mabe

Thank you for sharing this info. As a museum professional, I know how difficult change can be to implement. Your initiative to conduct in-depth analysis of the costs of each program is particularly inspiring. There are many programs at my site that seem to continue simply because of nostalgia rather than sustainability. I think the time has come to do some reflection; thank you for leading the charge to find a better model for history sites.