This article originally appeared in the May/June 2021 issue of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

Pensacola MESS Hall met the community where it was to demonstrate the power of herd immunity.

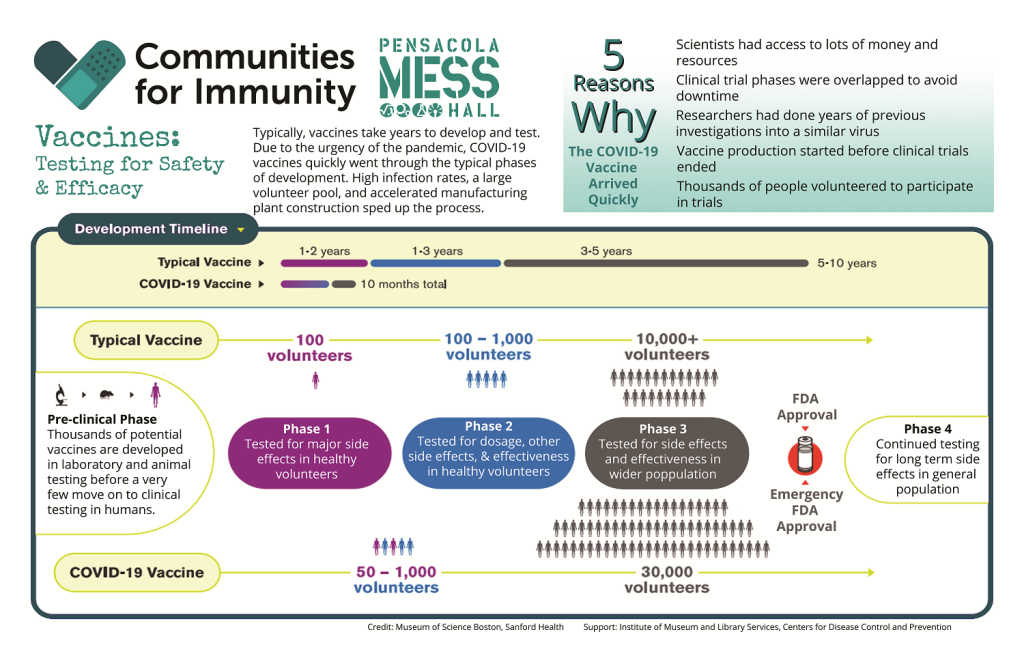

The Communities for Immunity initiative launched at a critical moment during the pandemic. With the rollout of the vaccine, the initiative sought to help US museums, libraries, and tribal organizations leverage their role as trusted community partners to build vaccine confidence in their communities.

A total of 91 museums, libraries, and tribal organizations received $1.6 million in two rounds of funding—with awards ranging from $1,500 to $100,000—to bolster vaccine confidence at the local level. From bringing vaccine clinics to underrepresented communities to combating misinformation and explaining the science behind the vaccines, this work showcases the humanity, ingenuity, and heart that exists in these museums, libraries, and tribal organizations.

Pensacola MESS Hall, a hands-on science museum located on the panhandle of Florida, received first-round funding from Communities for Immunity. The museum, which has six staff members, ventured beyond their usual outreach events to take the science of herd immunity directly to their community members.

A Different Kind of Event

When Megan Pratt, founder and executive director of Pensacola MESS Hall, and Sarabeth Gordon, the museum’s education director, went to their board with the idea of participating in Communities for Immunity, they were met with apprehension.

Community outreach was nothing out of the ordinary at MESS Hall. In the busy summer season, two full-time staffers attend around 75 outreach events, delivering science performances to crowds that sometimes exceed a hundred children and adults. They field dozens of questions about MESS (which stands for mathematics, engineering, science, and stuff), answering them with “rapid science,” quick and straightforward explanations to FAQs on topics ranging from probability and gravity to black holes and seashells, in an effort to create a science-literate community.

But this outreach proposal was a bit different. They wanted to set up a booth six times at four venues where people weren’t necessarily looking for a science demonstration: a seafood festival; the Soul Bowl, a youth football, soul food, and public safety festival at a local stadium; a health event at the mall; and three times at Gallery Night Pensacola, a popular event where the city closes the main street to motor vehicle traffic and lifts open-container laws.

How would the public respond to talk about COVID-19 and vaccines when all they wanted to do was have a good time and temporarily forget how a virus upended the world’s economy and claimed so many lives? COVID-19 and the vaccines came with emotional baggage, and some people would be drinking alcohol. “What if someone got violent?” the board asked. “Don’t worry,” Pratt told her board, dismissing their concerns with a wave of the hand, “Sarabeth is a black belt. She’s got us covered.”

“Truthfully, we never felt physically scared,” Pratt says. “But there were nights that were especially exhausting.” This outreach wasn’t the performance to a crowd they were used to. Instead, they were talking to up to 350 people individually.

When Pratt and Gordon applied for Communities for Immunity in August 2021, only 38 percent of the county had received at least one dose of the vaccine. Their target audience would be the 15 percent who identified as vaccine hesitant (not the vaccine resistant). Every sentence they said was tactfully crafted. Comments like, “So you’re pro-vaccine?” had a planned response of “We are here to share the science behind the vaccine so that you are better informed and able to make a decision.”

While their intention was to build vaccine confidence, that’s not what they spoke about, at least not directly. Instead, they explained herd immunity using a kid’s toy as a prop.

The Basics of Science Communication

Like many museums worldwide, MESS Hall was hit hard by the pandemic. In the summer of 2020, to celebrate the 1970 founding of the EPA, they planned an exhibition showcasing 50 years of environmentalism, but the pandemic changed those plans.

MESS Hall had experience addressing controversial topics. They planned to broach the concept of anthropogenic climate change with something every person could agree on: building dams impacts the environment. “You don’t lead with controversy,” Gordon says about the basics of science communication. “You don’t start with a challenge. You start with something everyone agrees on.

“With public health, everyone agrees on handwashing. So that’s how we approached Pop Its.” Pratt and Gordon used Pop Its, a simple fidget toy akin to bubble wrap, as an interactive game to educate people about herd immunity in an innocuous way while showcasing how disease spreads. The “pops” in the Pop Its represented individuals in the general populace. Once “infected,” adjacent pops are infected or spared based on their color (vaccination status).

Pratt and Gordon knew they had to make these topics as approachable as possible. “It’s cool to have nice and shiny equipment, sleek tech things, but it’s just easier to teach herd immunity with some colored dots on a kid’s fidget toy,” Gordon says. “We’re trying to teach them about the changing nature of science to build a mental model.” Those models are the beginning steps to seeing science as a process rather than a series of facts.

Another rudimentary tool Pratt and Gordon use in aiding scientific thinking in children and adults is an opaque Mystery Tube: a simple PVC pipe with four or five shower loofas wired through it. You pull one loofa and a different one moves—usually the one you wouldn’t have expected. The Mystery Tube helps people define a problem, make observations, form a hypothesis, conduct an experiment, and draw conclusions—the basic steps of the scientific process.

In these demonstrations, Pratt and Gordon waited for those aha moments—when a person’s face changes after figuring something out on their own. In that instant, they are doing science. Pratt isn’t shy about telling people they aren’t scientists—she openly corrects caregivers and teachers when they congratulate 7-year-olds on becoming a scientist. “We can’t let people think that anyone who breathes is a scientist. They can think like a scientist and do science, but they are not scientists … yet.

“I don’t understand immunology. I don’t know how all of it works, but I have learned to put my faith in experts,” continues Pratt, who has a Ph.D. in neurobiology from Harvard University. “People want to understand, but most can’t. This is too big. There are so many moving parts. But with the Pop Its and the Mystery Tube, they get to discover the science themselves. They own that knowledge because they found it.”

Pratt and Gordon can report the number of people they have talked to (approximately 800), but their impact will take a little longer to quantify. With 91 institutions producing qualitative and quantitative reports, the Communities for Immunity assessment team is currently working through that data, identifying patterns and strategies that prove effective in building vaccine confidence.

But Pratt and Gordon could see glimmers of their impact in the many detailed conversations they had with community members. For example, they recall a military service member, who was vaccinated because of a mandate, starting to imagine a virus spreading through a carrier or submarine or at one of the five military bases in the Pensacola, like it did on the Pop Its game he was holding.

They hope they changed some minds, equipped the vaccine confident with talking points to address questions and misinformation from vaccine-hesitant friends and family, and inspired people to be curious, ask questions, and pursue knowledge so that down the road, they can help others make better-informed decisions.

Confronting Controversy

Pratt and Gordon applied for Communities for Immunity on behalf of MESS Hall because they felt compelled to. “It’s so hard not to be able to do something when you know there are things that can be done,” Gordon says. “This was our chance to do something for our community that would have a positive effect—and dip our museum toe a little further into dealing with controversial topics.”

While science performances elicit somewhat predictable reactions, having individual conversations with hundreds of people presented so many more variables: impulsive reactions, quotes of misinformation, conflicts between family members visiting the booth. “Those nights were especially exhausting,” Pratt says. “It’s so tiring but so fulfilling at the same time.”

Having at least two people at the events was a requirement, as it is for any MESS Hall outreach event. There’s even an established post-event wind-down process. As Pratt and Gordon packed up the Communities for Immunity booths and walked back to their vehicles, they would debrief about what went wrong, what went right, what they should try next time.

It’s important to have somebody you can talk to and just say, ‘That was crap’ or ‘That was good,’” Pratt says, acknowledging that much of their success comes from the trust held among the team.

When children and adults enter the museum, the MESS Hall team greets them with a Mess Kit so visitors can immediately start playing with hands-on activities or experiments. It’s how the museum sparks curiosity and gets its audience to begin to think critically about the scientific process. These activities and exhibitions build a knowledge base that helps visitors see science and its advancement as an iterative process. That was also the goal during the Communities for Immunity demonstrations.

It’s why MESS Hall stepped out from its usual outreach event, targeting audiences that may not necessarily visit their museum. “A lot of people disagreed with us about the science behind the vaccine,” Gordon says, “but a lot of them took our card. Some will come through our doors later. In that case, we’ve done something. We got them curious.”

This public health disaster won’t be the last one humanity faces, but as trusted community partners, museums can create safe spaces to tackle these societal challenges. While the staff at Pensacola MESS Hall may not see their impact on COVID-19 firsthand, they have sown seeds for their community to experience a better, healthier future.

Partners in Science

Communities for Immunity is an initiative of the Association of Science and Technology Centers; Institute of Museum and Library Services; American Alliance of Museums; and the Network of the National Library of Medicine; with support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and in collaboration with the American Library Association; the Association of African American Museums; the Association of Children’s Museums; the Association for Rural and Small Libraries; the Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries, and Museums; and the Urban Libraries Council.

Resources

Find vaccine confidence resources at comunitiesforimmunity.org.

Comments