My focus this year is on exploring the ways museums serve as essential infrastructure for their communities: improving education for our children, creating livable communities for our elders, fostering mental health, helping prepare for and recover from disaster, and pioneering sustainable growth.

When I spread this message in lectures and workshops, I’m overwhelmed by the number of museum people who chime in with “yes, and…” sharing how their museums contribute to these pillars of community support and ideas for how museums could do more.

Every now and again, however, someone pushes back. Which is great—I rely on smart critics to help me hone my thinking, challenge my assumptions, and do a better job of making my arguments. In this case, the push back takes the form of, “But what about mission?” Or, more explicitly, “Doesn’t doing [this work] constitute mission creep?” I’ve been walking and thinking on that challenge and am ready to share a first draft of my response for your consideration.

First, Why is Creep Bad?

I worked in museums for fifteen years before coming to AAM, and then intimately with museums in MAP and Accreditation for another decade. I understand EXACTLY why people working in museums invoke a firm rule against creeping missions. We want a shield to defend against the misuse of museum resources by people with power or influence in the pursuit of private passions, shiny objects, or easy money. This might take the form of a trustee or donor who wants to launch a new area of collecting around their personal area of interest. Or staff who start new initiatives tailored to what a foundation is willing to fund, rather than what the museum (or its community) needs. Being pulled hither and yon by individual interests can result in a museum wandering all over the place, without having any significant impact in any one area of endeavor.

So yeah, there are examples of bad creep. And I’d argue that the root of their badness is that they are driven by an inward focus on what the person exercising power wants, rather than an outward focus on the effect the museum is having on the world. Bad creep results from listening to people who control resources, rather than the people we are trying to serve. But I think we often invoke creep because we’ve drawn inappropriately narrow lines around what we can and should do. Sometimes those lines are a reflection of preference—and privilege.

Creeping Beyond What?

It’s worth remembering that the phrase “mission creep” originally applied to military operations, referring to the danger of escalating the objectives of an operation to the point where failure was inevitable. (Not to mention resulting in unnecessary death and destruction in the process.) In that context, it focuses attention on the need to have a tightly defined objective in a situation that frankly one would have rather avoided anyway, and to withdraw once that objective is accomplished. It’s been applied in the nonprofit field, a very different field of endeavor, to critique a lack of focus, or drift away from the original mission. I think porting the term from war to human services, or arts & culture, comes with unnecessary baggage. As philanthropy critic Vu Le has pointed out, “Organizations led by marginalized communities often have broad missions,” because (and I’m paraphrasing here), those communities often have broad needs. And I wonder to what extent the narrow and exclusive focus of museums has historically been made possible by the privilege of their founders, funders, and the core audiences they have served.

Looked at from a different perspective, “mission creep” is often a side effect of the mission itself. This happens, for example, when missions create artificially narrow constraints by focusing on the mechanisms of the work (collect, preserve, interpret) rather than on the change an organization wants to make in the world. By contrast, if a museum’s mission is “transforming the nation’s relationship with science and technology” (Museum of Science, Boston); or to “deepen the understanding of past choices, present circumstances, and future possibilities; strengthen the bonds of the community; and facilitate solutions to common problems” (Missouri History Museum), or to “preserve, promote, and propel the right of all people to a place where they can live and prosper—a place to call home” (National Public Housing Museum), it is well within the boundaries of mission to serve as a COVID-19 vaccination site (MSB), hold a community forum in the wake of the police shooting of Michael Brown (MHM), or operate an entrepreneurship hub to foster the creation of small businesses and cooperatives (NPHM).

By keeping an open mind about what kinds of behavior and activities are appropriate for a museum, organizations can find many such opportunities. Sometimes that is going to result in tackling critical issues in a museum-y way. (For example, the Birmingham Museum of Art exploring body image and mental health through the lens of historic and contemporary art.) Or it might result in surprising actions like putting a refrigerator in the parking lot to distribute free food (Anacostia Community Museum), piloting a guaranteed income project for artists (Yerba Buena Center for the Arts), creating housing for homeless artists (Wende Museum), or providing an alternative sentencing program for youth in the criminal justice system (Clark Art Institute).

So maybe we need to reexamine the lines we draw around our work and consider whether “creep” is sometimes showing us where we ought to expand our boundaries. That kind of challenge may productively nudge museum people to think beyond the museum-specific, scholarly, and academic aspects of our work.

Why the World Needs More Creep

Perhaps in a more functional world it would be enough for a museum to focus just on being great at preserving and interpreting art, or science, or history. If, for example, we had systems that equitably addressed everyone’s basic needs and fundamental rights. But we don’t. We live in a patchwork of imperfect solutions that leave many needs unmet and many people deprived of rights.

In this era of growing partisanship and threats to functional democracy, it’s unlikely we will be able to mend these frayed systems through government reform. Rather, it’s going to take a “whole-of-society” approach, with organizations of all types pitching in, to transform this patchwork into a functional garment that keep our communities healthy and safe from harm. Schools provide free breakfast because students can’t learn well when they are hungry. Libraries provide information about where to find food, shelter, showers, and connections to social services because many people without housing use libraries as a place of refuge. Museums are integral parts of our social and economic systems. They can use their power and authority to reinforce the status quo (if only through inaction), or they can do their part to improve these systems where they fall short. As trusted thought leaders, museums can empower their communities to imagine and test entirely new systems based on equity and inclusion.

Even if we (the residents of the USA) did reform our basic systems of education, justice, housing, employment, and care to be more equitable, in the coming century our country will experience shocks that require organizations to contribute to an integrated response. It’s impractical to create standing systems large enough to respond to all the challenges we face. The current pandemic is a case in point: while our core systems certainly could have been better prepared to test, vaccinate, and communicate, the ad hoc response by businesses, nonprofits, and government demonstrates the resilience and power of organizations stepping up to do what needs to be done. Some states have already begun to create such flexible, scalable systems of response. For example, California, instead of maintaining a huge standing workforce of emergency responders, pulls state employees (including museum staff) from their regular jobs to act as disaster service workers.

Creeping Our Way to Deeper Impact

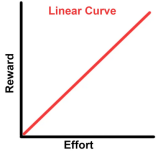

Sometimes we fall into the habit of assuming that improvement looks like this:

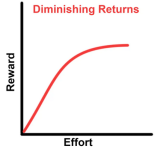

Actually, it looks more like this:

Plot effort against improvement and you get what is known as an asymptotic curve. At the beginning of the curve, you can get a big return on your investment of time and money. The better you get at something, the smaller your return on the resources you pump into the system. And as you approach theoretical perfection, it takes more and more effort to yield relatively tiny results. This curve is also sometimes called a Pareto Distribution, and illustrates what is often called “The Law of Diminishing Returns.”

Having worked with the American museum community for over twenty years at the Alliance, I can say with confidence that most museums are pretty good at what they do. Many museums (whether or not they decide to get accredited) are excellent at the core aspects of being a museum.

When a museum is already pretty dang good at core museum functions like collections care, or exhibits, or programs, even large investments of time, money, and attention are only going to yield tiny changes in impact. At some point, we pour resources into these activities because those are the results professionals care about with regard to their own professional standards. But if you consider museums as stewards of public resources, those resources may well do the most good if applied to new challenges, which may well involve working outside the traditional museum framework with regard to focus or format.

It’s Not Creepy to Be Compassionate

Finally, I’d argue that “creep” is sometimes used as a pejorative word for “going out of our way to do the right thing.”

Let me offer a person-centered analogy. Say I’m a doctor. (Make it a brain surgeon while we are at it, and a damn fine one, too. I save hundreds of lives a year through my expertise.) I’m driving home on a dark and stormy night, and I see someone struggling to change a tire at the side of the road—a young adult, with a toddler standing beside them, soaked and miserable.

Do I stop and see what I can do to help? Even if I don’t want to endanger my valuable hands, I could call for assistance (maybe their phone is dead, or they don’t belong to AAA). I could offer to take care of the toddler while they change the tire. I could stop my car a few dozen yards back, with the blinkers on, to help ensure another driver doesn’t plow into them in the dark.

Or do I say to myself, “I’m a surgeon, not a mechanic!” and drive on by?

Being a great doctor doesn’t justify being a jerk. By contrast, however, I think being a good human being can make someone a better doctor. Similarly, “mission creep” is sometimes invoked as an excuse for a museum not doing the decent organizational thing by helping its community when it can. Being a good, or great, museum doesn’t let you off the hook for being a good neighbor. In fact, I would argue that being a good neighbor will make a museum better at what it does, by cultivating empathy, connection, and an attitude of service to the public. What do you think? Please continue the conversation with comments on this post.

Recommended Reading

From Being about Something to Being for Somebody: The Ongoing Transformation of the American Museum, Steven Weil (1999). MIT Press, American Academy of Arts & Sciences.

We need to rethink the concept of mission creep, Vu Le, Nonprofit AF blog, August, 2021.

I like the idea behind this article and I think this is your best line, “So maybe we need to reexamine the lines we draw around our work and consider whether “creep” is sometimes showing us where we ought to expand our boundaries. That kind of challenge may productively nudge museum people to think beyond the museum-specific, scholarly, and academic aspects of our work.”

However I have to wonder about the divorce between the idea and the implementation on a daily basis of that “creep” work. I think at institutions that can afford to do more that might be one thing. But unfortunately I’m not sure most institutions are in that position. I happen to work at a museum that is completely over extended. We have significant mission creep… which certainly comes from a good place, the desire to do more/be more for our community… but without the resources (namely enough staff, not to mention time or money) to do it well or effectively.

I think the notion of “creep” as a negative term is rightly designated, at least in terms of the individual worker. I don’t have the time, capacity, or will to take more on. At an institutional level this might be more of an acceptable notion. But coming from someone who is constantly dealing with “creep” in all forms… this just elicits a weary sigh from me.

I spent nearly 10 years working at a humanitarian and human services nonprofit organization. I am interested in the intersection of museums and social justice and currently pursuing a graduate degree with the hope of working in an art museum. As someone who visits a lot of museums and rarely sees people like me reflected in museum exhibitions and audiences, I believe strongly that museums should reflect and add value to the communities in which they are located, especially those which are public institutions. I have been reading Vu Le’s blog for years and am happy to see him linked and quoted in this post. I am thrilled to see his ideas in support of mission creep applied towards museums. I agree wholeheartedly. How can I help make this happen? I would be happy to help any museum interested in expanding their mission to support communities create a robust volunteer program to sustain these efforts. I developed and led a successful internship and volunteer program throughout my organization.