When museums design exhibitions with the nervous system in mind, they create more effective spaces.

How can museums create emotionally powerful exhibitions that support sustained visitor engagement? How do we design spaces that move people emotionally—without exhausting them?

This article originally appeared in the Nov/Dec 2025 issue of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

» Read Museum.

These questions are increasingly relevant for institutions that interpret traumatic or emotionally difficult histories. Whether addressing genocide, war, enslavement, forced displacement, or other legacies of harm and violation, many museums aim to provide visitors with more than historical content. They seek to foster critical thinking, empathy, reflection, and emotional connection. But in doing so, they also face an exhibition design dilemma: when content is immersive, urgent, and emotionally intense, visitors can struggle to stay present, learn, and return.

This dilemma shaped a recent collaboration between the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) and an interdisciplinary team of researchers from the University of Florida and the University of Oklahoma. With support from the museum’s Future Projects team, we piloted a biosensory-informed approach to understanding visitor experiences. This approach examines how museum environments interact with the body’s natural stress responses. Using wearable biosensors, spatial mapping, and post-experience interviews, we explored how visitors physically and emotionally respond to an iconic exhibition.

The goal was not to evaluate exhibition content, but to better understand audience pacing, emotional impact, and the conditions that support visitor reflection and learning. This work offers new tools for institutions engaging with emotionally complex material and supports a broader shift toward ethical, visitor-centered exhibition design practices rooted in collective care.

What we learned offers valuable guidance, not just for the USHMM but for any museum working to balance emotional resonance with visitor care.

Emotion as a Design Tool

Visitors often describe emotionally powerful exhibitions as unforgettable. Research backs this up: emotionally charged experiences activate memory, deepen empathy, and promote personal reflection.

For more than three decades, the USHMM has led the field in immersive, narrative-driven approaches to museum design. Its Permanent Exhibition, which spans three floors of historical content and features carefully curated artifacts and experiential storytelling, has been a model for how to convey traumatic histories to visiting audiences. Since opening in 1993, over 50 million people have visited the museum—many describing the experience as transformative. In planning for the future of its Permanent Exhibition, the museum invited our team to explore how new evaluation tools might offer additional insight into how visitors experience the exhibition today.

Designing for emotional resonance is not just about impact. It’s also about rhythm. Too much intensity without moments of pause may overload the nervous system, making it harder for visitors to stay engaged, especially with sustained or layered content. This is not a failure of design; it’s a natural physiological response. And it raises important questions: How can museums support the full arc of a visitor’s emotional journey? How can we help people not just feel deeply, but stay present, absorb complex information, and critically reflect on the experience?

Our team developed a pilot study to explore these questions using biosensors, spatial analysis, and post-visit interviews. Working closely with USHMM staff, we designed a study that would respect the existing visitor experience while offering new insights that might inform future planning.

From January 2021 through April 2023, we equipped more than 50 adult visitors with Empatica E4 wristbands that measured electrodermal activity (EDA), a reliable indicator of psychological stress or emotional arousal. These biosensors recorded visitors’ physiological responses as they moved through the Permanent Exhibition. We also mapped their movement through 19 specific exhibition zones and conducted post-visit interviews to gather qualitative reflections.

By synchronizing biosensory data with visitor pathways and post-visit reflections, we created a moment-by-moment map of how the body responds during a typical museum visit. This approach did not evaluate visitors’ satisfaction or emotional responses as good or bad—it simply made those responses visible in a new way.

The findings helped illustrate what many museum professionals already sense intuitively: immersive experiences are powerful, but they are also intense. Understanding when and how emotions happen can help museums support visitors more effectively through content that is intentionally designed to be complex, layered, and impactful.

What Visitor Physiology Can Tell Us

The biosensory data, when layered with spatial mapping and interviews, offered a new lens for understanding how visitors experience emotionally evocative museum environments. Rather than relying solely on what people remember or report, this method allowed us to observe emotional patterns as they unfolded in real time.

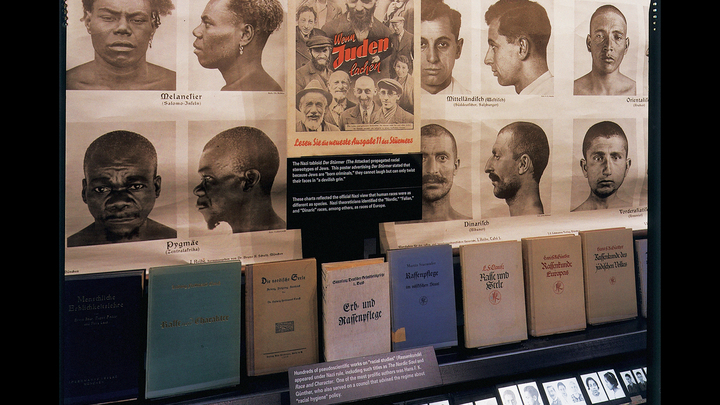

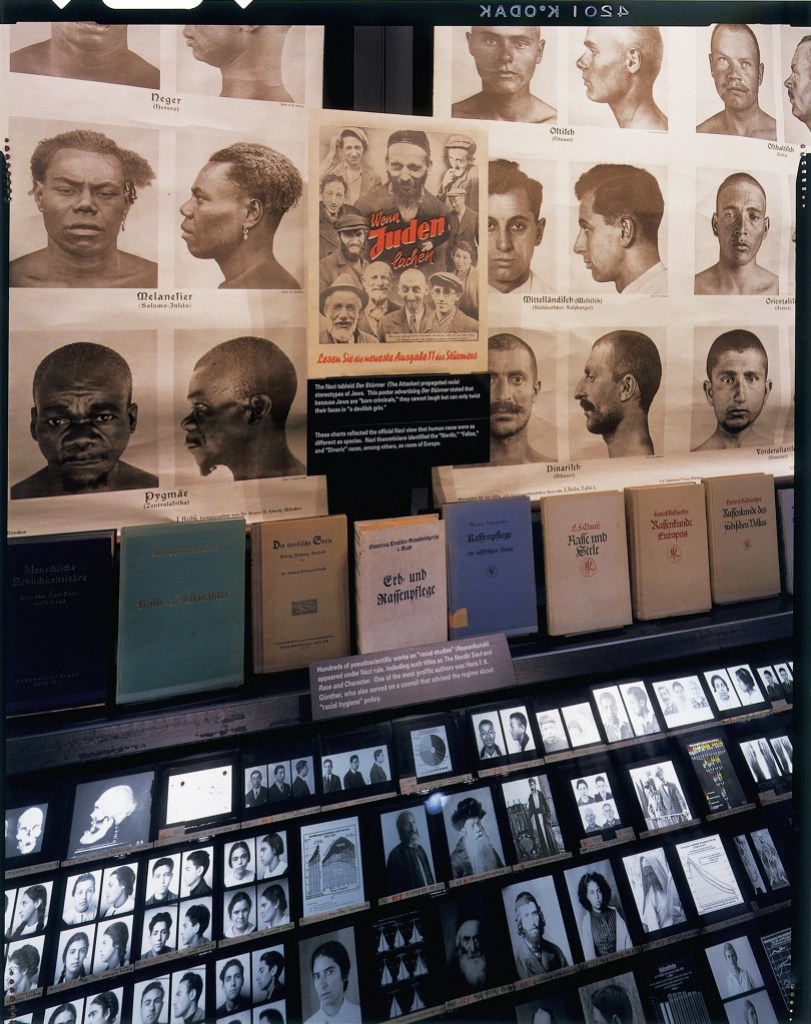

We observed consistent physiological peaks in areas with immersive content and exhibits addressing particularly sensitive themes. For example, on the fourth floor, visitors often registered heightened arousal in the “Science of Race” exhibit, where the history of racial pseudoscience is explored in chilling detail. This area appears early in the exhibition and sets a serious tone for the rest of the visit.

On the third floor, some of the exhibition’s most iconic elements—such as the rail car, model of Auschwitz, and shoes—elicited strong responses both in biosensory data and interview feedback. These spaces are powerfully designed and often cited as among the most memorable and moving parts of the visitor experience.

Importantly, our data also suggested a pattern of decreasing arousal immediately following these emotionally heightened zones. This was not a sign of disengagement or dissatisfaction. Rather, it aligned with a common physiological pattern: when the nervous system is activated for an extended period, it begins to downregulate. Visitors may describe this as needing a break, feeling emotionally flooded, or simply becoming quieter.

These findings underscore the powerful emotional impact of the exhibition’s design. At the same time, they highlight opportunities to support visitor engagement by making space for recovery and reflection, allowing emotional intensity to settle before new content is introduced.

Designing with Rhythm and Recovery

One of the clearest takeaways from our study is that visitors benefit from emotional pacing. Just as a well-crafted film or novel includes moments of quiet between climactic scenes, exhibitions can create space for visitors to process what they’ve experienced.

Designing for emotional rhythm might include:

- Balancing high-impact areas with lower-intensity content zones

- Providing seating or contemplative spaces following intended emotional climaxes

- Using changes in lighting, sound, or spatial openness to signal thematic shifts

- Offering varied interpretive modes—visual, sensory, and text-based—to meet different emotional and cognitive needs

These strategies may help not only with comfort, but with learning and retention. When visitors feel emotionally supported, they are more likely to stay engaged, return to the content, and reflect on what they’ve seen.

Supporting a Trauma-Informed Future

The biosensory-informed method we piloted complements a growing movement within the museum field to adopt trauma-informed practices. These approaches recognize that trauma is widespread and that museum experiences can have unintended emotional consequences. Being trauma-informed doesn’t mean softening content. It means understanding the diverse ways visitors may experience a space and taking care to minimize unintended harm.

Trauma-informed thinking has long informed the curatorial, interpretive, and educational practices of memorial museums. Our study was one small part of a broader commitment to visitor interpretation at the USHMM, especially in the context of balancing historical accuracy with emotionally challenging content.

As more museums experiment with new forms of visitor interpretation and evaluation, museum leadership will continue to contend with how to engage audience emotions ethically. Whose nervous systems will be prioritized, for example, and how will this care be perceived and experienced across a range of nervous systems? As museums seek to engage the public with honesty and care, they must think not only about what stories are told, but how they are physically and emotionally experienced in museum spaces.

As our study shows, biosensory tools can be a valuable complement to traditional visitor interpretation methods. Making emotional responses visible can help museum teams bring greater empathy to exhibition design by identifying emotional arcs alongside narrative arcs. This doesn’t mean every museum needs a wearable tech study. But museums should consider how their exhibitions feel—not just in theory, but in the body.

Museums are places of learning, remembrance, and connection to ourselves and others. They are also sensory environments. By designing with the nervous system in mind, we can create spaces that welcome, challenge, support, and invite visitors to return.

5 Tips for Designing with the Nervous System in Mind

Consider the emotional arc of your exhibition. Narrative arcs guide the visitor’s experience and help set expectations inside museums. Identifying emotional arcs can similarly reduce surprise and build trust for visitors.

Plan for emotional pacing. Alternate higher-intensity spaces with lower-intensity ones. A balanced, well-sequenced exhibition layout helps visitors stay grounded and engaged throughout their visit.

Build in spaces to pause. Include areas for rest, reflection, or stillness. Even a bench, soft lighting, or an open sightline can help the body regulate after difficult or highly stimulating content.

Offer different ways to stay connected. Varied modes of interpretation—visual, sensory, and text-based—can meet the emotional needs of audiences differently, particularly those with sensory sensitivities. Offering multiple narrative pathways empowers visitors to meet their own emotional needs.

Test your design choices early. Pilot walk-throughs to understand not just how content is received, but how it feels. For example, pay attention to moments of excitement and discomfort to identify emotional climaxes and plan for audience recovery.

Resources

Jackie Armstrong, “3 Trauma-Informed Practices for Museums to Follow,” AAM Blog, May 12, 2023

bit.ly/44TDuRi

Dan Luo, Lieve Doucé, and Karin Nys, “Multisensory Museum Experience: An Integrative View and Future Research Directions,” Museum Management and Curatorship, 2024

doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2024.2357071

Jacque Micieli-Voutsinas and Angela M. Person, “Using Biosensors to Map Trauma-Informed Heritage Design: Measuring Visitor Emotional Experiences and Affective Engagement at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Heritage and Affect, forthcoming

Laurajane Smith, Emotional Heritage: Visitor Engagement at Museums and Heritage Sites, 2021

Marzia Varutti, “The Affective Turn in Museums and the Rise of Affective Curatorship,” Museum Management and Curatorship, 38(1), 2023

doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2022.2132993

Acknowledgements

The study described here was made possible through the collaboration of Dr. Jacque Micieli-Voutsinas (University of Florida), Dr. Angela Person (University of Oklahoma), Silvina Fernandez-Duque (US Holocaust Memorial Museum), and Dr. Chris Black (University of Oklahoma), with support from Russ Sitka, Sara Pitcairn, Michael Haley Goldman, and others. The team is grateful to Dr. Tedi Asher (Peabody Essex Museum) for her insights. This research was supported by the vice president for research and partnerships and the Data Institute for Societal Challenges (University of Oklahoma), a faculty development grant (Skidmore College), a research incentive award (University of Florida), and the Future Projects team at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Jacque Micieli-Voutsinas, Ph.D. is Assistant Professor of Museum Studies at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

Angela M. Person, Ph.D. is Associate Dean for Research and External Engagement at the University of Oklahoma in Norman.

Silvina Fernandez-Duque is Director of Future Projects at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC.

Christopher Black, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of Health and Exercise Science at the University of Oklahoma in Norman.