This article first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Fall 2025) Vol. 44 No. 2 and is reproduced with permission.

Storm King Art Center, located in New York State’s Hudson Valley, connects visitors with works of art set within a vast and varied landscape (intro image).[i] At any given time, approximately 120 works of modern and contemporary art, varying in scale from human-size to monumental, are on view across the 500-acre site.

As an outdoor museum, the landscape of the Art Center and its galleries are synonymous. Paraphrasing one of our founders, H. Peter Stern, Storm King sees the earth as our floor, the sky as our ceiling, and the mountains as our walls.[ii] A visit to Storm King spans time and space: a visitor might view a work of art from a half mile away and, later, find themselves standing beneath it.

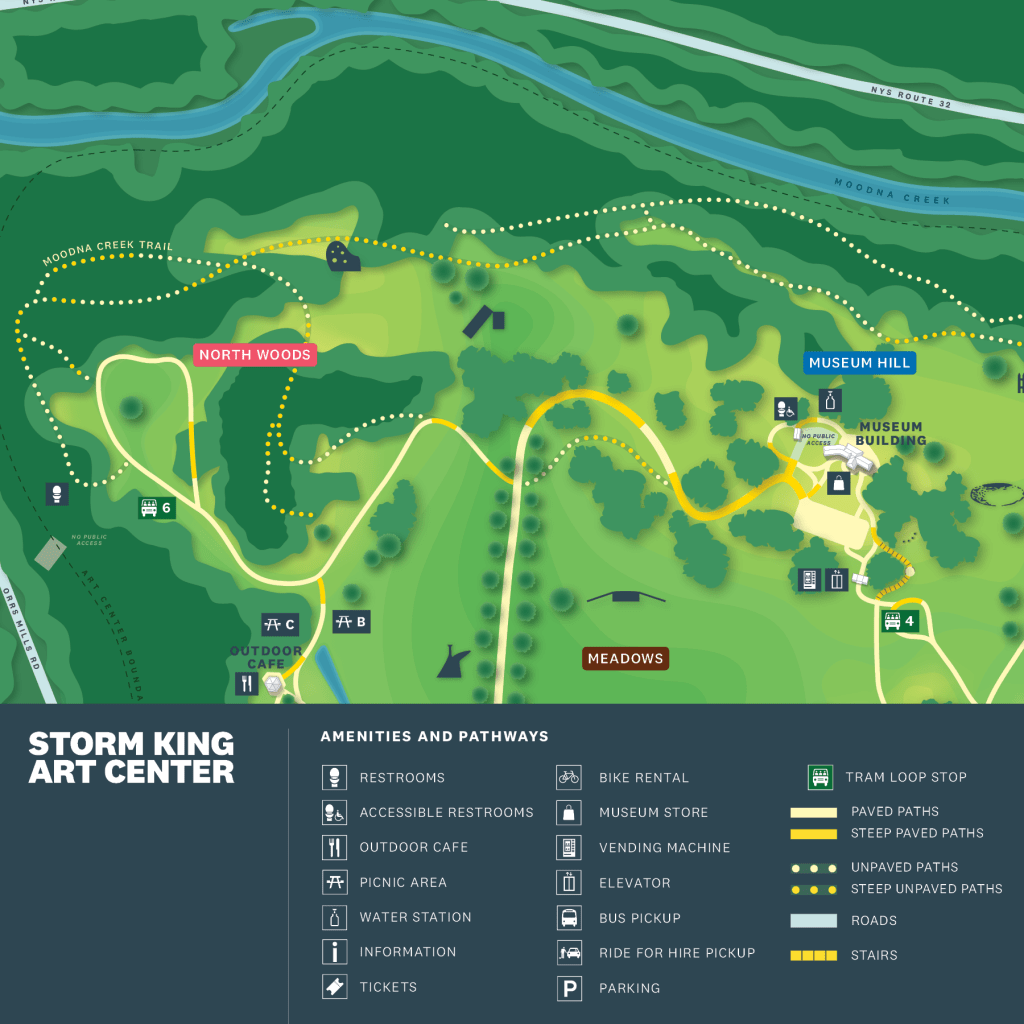

Storm King was founded in 1960, 30 years before the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Historically, the design of Storm King’s outdoor galleries assumed visitors would traverse the space on foot; have the ability to walk significant distances on paths of varying materiality; be able to navigate uneven and hilly terrain; and be comfortable in the elements with limited access to shelter, seating, water, and restrooms (fig. 1).

In an effort to address some of the Art Center’s physical accessibility challenges, Storm King embarked on two linked physical accommodations in the early 2000s: the addition of wheelchair-accessible trams to support visitors traveling across the broad site and the construction of an elevator pavilion to assist visitors in navigating the approximately 40-foot elevation change from the Art Center’s fields to the museum building, which sits atop a hill and contains indoor galleries.

These interventions were effective but limited. In the past seven to nine years, the Art Center has moved from its practice of bringing specific solutions to bear on individual inclusion challenges to a more holistic approach grounded in the insights of people with disabilities. This essay, authored by staff leaders of this effort, will outline three processes that advanced this holistic approach, with the hope that these constructs will be of use to other institutions striving to provide access to landscapes and historic buildings:

- Building Consensus

- Building Resources and Skills

- Building Partnerships

Building Consensus

From 2018 to 2022, three seemingly discrete initiatives called attention to both the need and the opportunity to holistically address inclusion writ large and physical accessibility specifically. In 2018, Storm King embarked on our first-ever capital project, which opened in spring 2025 with a new entrance and a purpose-built facility for conservation, fabrication, and maintenance. In 2021, we adopted a written plan for diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion, called the I:DEA Plan. Simultaneously, Storm King worked with artist RA Walden on a temporary exhibition that centered the artist’s experience of disability. These activities required cross-institutional discussion—lots of it.

In the first phase of design for the capital project, we engaged consultant Josh Safdie of KMA Architecture + Accessibility (KMA) to provide staff and the architectural team with an overview of the ADA and best practices for physical accessibility. This simple activity, a one-hour slide show, unpacked the spirit of the work and revealed a host of opportunities. It crystallized recognition that accommodations support a wide range of people, and it empowered staff to take small actions toward addressing what seemed like a daunting whole. Storm King directed the architectural team to follow universal design (UD) principles for the new buildings and landscapes, that is, to design them for a broad range of users from the outset. In the capital project, “the main path is the accessible path; the main counter is the accessible counter.” Storm King also engaged KMA to conduct a site accessibility audit which documented the pathways, benches, signage, trash receptacles, and other site furniture. A concept of “lily pads” emerged from Safdie’s counsel: the idea of co-locating key Storm King experiences (such as close encounters with or long views of works of art) and visitor amenities (seating, placemaking maps, tram stops, etc.). Concentrating site improvements into lily pads delivers a richer, more accessible experience for visitors than what would be possible if those same amenities were spread out across the site. It is also efficient and cost-effective for the institution.

The I:DEA Plan, adopted in 2021, recognized the interconnection of governance, operations, and programming in amplifying inclusion at the institution. In terms of our facilities, the plan built on the guidelines developed in the accessibility audit, establishing a wish list for future improvements in signage, site furniture, pathways, and visitor amenities, that, due to budget, would unfold over time. The I:DEA plan also joined physical improvements and programmatic ones. Most of all, the collaborative hours trustees, staff, and consultants spent conceptualizing, drafting, and implementing the plan established a shared understanding of opportunities and challenges, allowing for an ongoing open-minded re-examination of long-held institutional practices.

![] An artwork composed of three concentric circles rests low to the ground in a grassy field with tall trees beyond. In front of the artwork, two sturdy wooden benches with backrests and arms have been placed in a leveled, gravel area within viewing distance of the work and its interpretive placard.](https://www.aam-us.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Fig-2-SKAC-RA-Walden-1151.jpg?resize=768%2C1024)

One such reconsideration involved Storm King’s trams. Until 2021, trams operated on a limited schedule, beginning a loop once per hour on weekdays and twice per hour on weekends, with a pre-recorded audio tour. The tram stopped at several points, and while visitors were welcome to get on or off at any stop, almost everyone stayed on for the full loop to get an overview of the Art Center. While the tram program was developed to facilitate access for visitors with small children, older visitors, and those with disabilities, in practice it was “first come, first served.” As visitation at Storm King increased, visitors seeking this service often encountered a full tram, leaving some people disappointed and others without an essential transportation tool.

Visitor feedback, along with a growing awareness of accessibility practices, prompted us to bring together a cross-departmental team to review the purpose of the tram and revise its operations. When we redefined the tram as an essential access tool rather than an interpretive experience, we were able to develop a more accessible system with the same resources. Now, the tram makes six stops, each at a scheduled time, and completes two loops of the campus each hour. The limited and updated narration is attuned to orientation, announcing what is near each stop, and thus encouraging people who are able to get on and off to explore—knowing another tram will come by in 30 minutes—while welcoming those who need a seat to stay on for the full loop.

Similar reflection impacted RA Walden’s installation, access points // or // alternative states of matter(ing).[iii] Walden identifies as a queer disabled artist whose work “seeks to disturb overly simplistic understandings of the disabled body, looking to bring an ethic of care, [and] a connection between the land and the body.”[iv] Originally slated for 2021, Walden’s exhibition was delayed until 2023 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and so that Storm King could be better prepared to support the artist and visitors during an exhibition that explored “the experiences and access needs of disabled people, which are often met with disbelief, if not disdain, from the medical establishment and society” (fig. 2).[v] Our efforts to sharpen operational procedures gathered momentum with a formalized admission policy that provides free admission for caregivers attending with disabled visitors and the creation of a distinct accessibility webpage that supports visitors in learning about both the resources and barriers at Storm King before they arrive, thereby allowing them to make informed decisions about their visit. Concurrently, Storm King worked with artist Martin Puryear to develop an accessibility plan for his permanent site-specific commission Lookout (2023), set on one of our highest hills. Key to this plan was the purchase of a wheelchair-accessible cart, as our trams cannot navigate the hill.

During this period, confidence and commitment amplified across the institution, with access becoming a core value. Study, policy, and action became reciprocal activities, drawing in many voices and building on one another in an affirming, iterative manner.

Building Resources and Skills

While it was not a revelation that Storm King would never be ADA-compliant across the entirety of our 500 acres, the site accessibility audit, alongside work on the capital project, I:DEA plan, and preparation for the RA Walden exhibition, helped to broaden our thinking beyond isolated barriers and toward a system of access. As we removed physical barriers to access, we also began to think about how we could bridge the inevitable gap between accessible nodes with programs, services, and staff, ensuring that every visitor has access to a very rich and very Storm King experience—even without physical access to every part of the site. How could we give staff the skills to confidently bridge the gap with gracious hospitality? This question motivated our successful application for a Museums Empowered grant through the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), a funding program that supports staff training and development. Our three-year project, which began in September 2022, empowered our staff with the knowledge and skills to create a more inclusive visitor experience through both hospitality and accessibility initiatives.[vi] It has been transformative.

The work we’ve undertaken has purposefully intertwined conversations about accessibility and hospitality, recognizing that they are interdependent and that best practices in one realm inform and overlap with best practices in the other. What benefits a visitor with a disability often benefits all visitors. This full embrace of Storm King’s responsibility to provide a superlative visitor experience and to be welcoming to all has given new context to decision-making across teams and has touched all levels of institutional management including our board, administrative staff, grounds staff, frontline staff, and volunteers. The grant has resulted in tangible outcomes such as a library of training materials, updated best-practice manuals, more robust accessibility information on our webpages for visits and programs, and a formal Accessibility Advisory Committee (discussed below). Beyond these deliverables, it has also produced a palpable shift in culture. During a share-out at an all-staff planning retreat in the fall of 2023, staff members across departments continually raised ideas related to accessibility, indicating that a broad range of staff considered access to be part of their work.

We found an invaluable partner in Turnstile Studio, our main consultant on the grant. Turnstile supports capacity-building efforts of museums to more effectively welcome, engage, and inform visitors. Cindy VandenBosch and Andrew Gustafson of Turnstile, along with their colleagues, have modeled what it means to center visitors and disabled voices from the start. Our work with them kicked off with a rigorous assessment that included staff and volunteer focus groups and surveys, a review of public communications and internal procedures, and, perhaps most importantly, the feedback of 10 visitor-experience consultants who came to Storm King in fall 2022 (fig. 3).

These consultants brought expertise in transit, customer service, accessibility, and the arts, and most have lived experience with disabilities. They provided extensive feedback on their visits to Storm King, creating a keystone set of qualitative data that informed the project and provided a baseline for measuring progress. The assessment identified initial challenges and proposed strategies for addressing them in the near term, including providing better access to information on accommodations for visitors and staff; learning directly from those with disabilities; and training staff on skills such as using the tram ramp and navigating communication barriers (fig. 4). These strategies were workshopped with a small interdepartmental working group, discussed with the full staff, then reviewed with the Board’s education committee and presented to the full Board. This initial assessment has been a launching point for the work, and as progress is made and lessons are learned, new strategies are implemented.

Flowing from this assessment, staff training has continued to center visitor voices. Guest speakers and audio and video clips from visitors, advisors, and consultants help staff connect general accessibility and hospitality principles to the experiences of individuals, anchoring our work in human connection. In one post-training evaluation, a staff member noted, “it was effective to speak to the people who spoke of their on-the-ground experiences of Storm King. . . . [W]hen you have a poignant connection with another human, as I felt I had in that meeting as I learned from your participants, it can really hit you very sharply and in a way that is extremely effective and true.”[vii]

Storm King also developed a number of resources as part of its Museums Empowered grant, including revised standard operating procedures that better integrate access and hospitality, adaptable training tools, and train-the-trainer modules. At the end of year one, 91 percent of staff and volunteers who responded to an evaluative survey felt more prepared to welcome visitors; ongoing surveys have consistently reflected greater confidence among staff and docents in supporting visitor needs.[viii] Policies, procedures, and resources reinforce this foundation of learning, empowering our staff to carry these skills into the future.

Building Partnerships

Our work on accessibility aspires to honor the disability rights mantra, “Nothing about us without us,” and our strategy around engaging the disabled community has evolved. After completing the earlier physical site accessibility audit, we wanted to share more information with visitors and set out to create an access map with graphic designers from C&G Partners. We engaged artist Finnegan Shannon, who takes access as a central theme in their practice and has experience working for and with cultural institutions, as an advisor.[ix] Shannon challenged us to consider why we were pursuing a separate access map when this information would be useful to visitors who might not think to request, or even accept, an access map. This head-smacking moment of clarity led us to shift course and work with the graphic designers to incorporate elevation, incline, ground surface, and stair locations into the general visitor map (fig. 5). In addition to this crucial input, Shannon shared broadly about their visitor experience. They emphasized the importance of providing visitors with choices as an accessibility strategy. For example, on-site transportation is more inclusive when there are many options on offer; a visitor might be best served by the tram, bikes, wheelchairs, or golf cart rides. From this we learned both to ask specific questions and to leave space for advisors to share more about their experiences, recognizing that we don’t know what we don’t know.

Through the IMLS grant, we have assembled a formal Accessibility Advisory Committee. Currently composed of five members with varied expertise in advocacy, accessibility, and the cultural sphere and a wide range of lived experiences with disability, the group has convened virtually and in person, and members are compensated for their time. Advisors’ candid feedback has shaped planning around tours, public communications, on-site amenities, and more. In addition, hosting the group in person was a moment of growth for our staff who learned from the process of preparing for a meeting that needed to cover much of the site, be physically accessible, and utilize verbal description, tactile materials, and ASL interpretation. While we relied heavily on Turnstile’s network in New York City to assemble our first Advisory Committee, the focus moving forward is to build regional relationships and strengthen our own networks as we renew the committee over time (fig. 6).

We have also been mindful to bring in disabled voices in ways that are specific to Storm King. As an artist-centric institution taking a broad and embedded approach to accessibility, it felt essential for us to include artists’ voices. In this we were guided by artist Carolyn Lazard, who writes in Accessibility and the Arts,“Supporting the cultural labor of disabled artists and thinkers must happen in tandem with infrastructural changes.”[x] Storm King included funding for presentations to staff by disabled artists in our IMLS project budget, hosting talks by artists including Finnegan Shannon, Sara Winston,[xi] Alison O’Daniel,[xii] and JJJJJerome Ellis.[xiii] These talks both illuminate the ways that disability and access can be a generative creative force and strengthen staff’s understanding of contemporary art.

Partnerships with consultants, artists, and advisors have deepened our understanding of accessibility as an ongoing, flexible, and multifaceted practice and will continue to guide our work.[xiv]

Next Steps

“Improving access is always a process in development and we’ve got to start where we are! So

wherever you are is a great place to start. . . . This is how we grow together . . .”—Sins Invalid

The end of this article is not a conclusion. Rather, this article has provided space for reflection aimed at furthering the work-in-progress of expanding inclusion. With the opening of its new entrance, Storm King can now invite visitors into its grounds knowing they will be supported by knowledgeable and hospitable staff and have access to restrooms, paths, signage, benches, trams, and other amenities that have been designed with access at their heart. As Storm King staff and visitors use these new facilities, consensus, learning, and partnership will be mined for further opportunities to move principles of access into more spaces for art, landscape, and people (fig. 7).

As we have worked to build buy-in, skills, and partnerships, we have learned that:

- Assessment is not just a measurement tool.

An assessment can establish the engagement of stakeholders by honoring their personal experiences and existing expertise.

- You don’t know what you don’t know.

Keep asking questions. The perspectives of both visitors and disability advocates are essential.

- Accessibility is not extra but integral.

Thread accessibility throughout existing practices, policies, and programs.

- Make it yours.

Find ways to connect the work to your core mission and unique culture.

- You will not be perfect.

When mistakes happen or barriers emerge, be transparent, be responsive, and keep trying.

Hannah des Cognets is Director of Learning and Engagement at Storm King Art Center in New Windsor, New York. h.descognets@stormkingartcenter.org

Amy S. Weisser was, through June 2025, Deputy Director, Strategic Planning and Projects, at Storm King Art Center. aweisser@aro.net

[i] “Storm King Art Center,” accessed July 19, 2025, www.stormking.org. The authors thank their colleagues for their dedicated support of and participation in this work, especially project team members Lakin Corbett, Associate Director, Visitor Experience; Theresa Padget, Visitor Experience Coordinator; and Bam Bowen, Visitor Experience Operations Coordinator, and consultants C+G Partners, KMAccess, and Turnstile Studio.

[ii] H. Peter Stern, “The Creation of Storm King Art Center: A Personal History,” Lecture at the Chautauqua Institute, July 1, 2003.

[iii] Walden’s installation was the 10th in Storm King’s Outlook exhibition series, which offers emerging and mid-career artists the opportunity to present a temporary large-scale outdoor project in the landscape.

[iv] “Statement,” RA Walden, accessed July 19, 2025, https://rawalden.com/Statement.

[v] “Outlooks: RA Walden, May 20–November 13, 2023,” Past Exhibitions, Storm King Art Center, accessed July 19, 2025, https://collections.stormking.org/Detail/occurrences/205.

[vi] “Storm King Art Center Empowered,” Federal Award #ME-251462-OMS-22. While in early 2025, IMLS funding for previously award grants was in jeopardy, Storm King was able to receive full funding for this grant prior to the end of work.

[vii] For the authors too, first-person narratives have guided this work. These include, Chloé Cooper Jones, Easy Beauty (Avid Reader Press, 2022); Georgina Kleege, Sight Unseen (Yale University Press, 1999); Andrew Leland, The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight (Penguin Books, 2024); and Alice Wong, ed., Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century (Vintage, 2020).

[viii] Unpublished reports submitted by Turnstile Studio (September 13, 2023, and November 14, 2024).

[ix] “Finnegan Shannon,” accessed May 23, 2025, www.shannonfinnegan.com.

[x] Carolyn Lazard, Accessibility and the Arts: A Promise and A Practice (2019) https://promiseandpractice.art/.

[xi] “Sara J. Winston,” accessed May 23, 2025, www.sarajwinston.com. Winston is a former staff member of Storm King, who advocated for conversation on accessibility during her tenure.

[xii] “Alison O’Daniel,” accessed May 23, 2025, www.alisonodaniel.com.

[xiii] “JJJJJerome Ellis,” accessed May 23, 2025, www.jjjjjerome.com.

[xiv] The three-year project, funded with more than $200,000 from IMLS and matched by Storm King with staff time, enabled a sustained and deep focus that would not have been possible otherwise.