In my study at home is a beautiful wooden couch handcrafted by my uncle Bob. It cleverly converts into a (narrow, hard) sleeper sofa when you lift the woven back. I was very happy to inherit this piece of family memorabilia, and always referred to it proudly as the Bob couch.

Until the day I came across a picture of it in an exhibit catalog about mid-Century Danish Modern furniture, and realized it was actually designed by Hans Wegner. At which point I did some sleuthing and discovered that the sleeper couch my uncle designed was a different one that used to live on our family’s cabin in New Hampshire. And I don’t know where that couch is, now, dang it.

This made me question: how many other pieces of my family history—even those attached to objects that act as anchors for memory—are false? How many not-quite-true stories have become enshrined in family lore?

If this was just a matter of me wrestling with the truth of my personal history, I wouldn’t be blogging about it. But it encapsulates a problem that faces our field. As I discussed last week, one major reason the public trusts museums is that people see our collections as prima facie evidence of “the truth.” Objects embody memories—they act as the physical placeholders of history. But what about when those memories aren’t true?

Brian Williams’ recent recantation of his account of getting shot down in a helicopter in Iraq in 2003 has provoked a flurry of press. Often the criticism or defense of his action hinges on this key point: did Williams lie, or did he truthfully relate an inaccurate memory? His job is on the line, which is bad enough, but the stakes can be even bigger. Last year’s uber-popular podcast Serial, revisiting a 15-year old murder trial that landed a teenager in prison for life, questioned whether the recollections of suspects, accusers or witnesses can be trusted, even if the people in question intend to tell the truth. Podcaster Sarah Koenig tackled the issue head-on in the penultimate episode: Can a murderer not remember s/he had committed the crime? Can s/he reshape memories over time?

Research has established that memory doesn’t store raw, unfiltered footage. Memory selects, edits, conflates and deletes. Even our recollection of high-impact events is strikingly bad. In one famous study a professor of cognitive psychiology, Ulric Neisser, interviewed students after the Challenger explosion in 1986. Three years later he re-interviewed them. “A quarter of the accounts were strikingly different, half were somewhat different, and less than a tenth had all the details correct. All were confident that their latter accounts were completely accurate.”

Now that we are beginning to understand how our brains make and store memories, it is clear that we are more likely to remember remembering (or remember the stories we have told about remembered events) than to remember the original events themselves. We can create false memories. Empathetic individuals can even “absorb” the memories of others, remembering their pain as their own (as dramatized in this fabulous animation—The Bloody Footprint—highly recommend). This ability to revise our personal histories can be tremendously therapeutic, boosting resilience and contributing to healing. But it wreaks havoc with any record of history that depends on personal recollection.

What does the malleable nature of memory mean for museums?

For one thing, it dramatizes the danger of relying on oral histories, which is problematic, given that our field has made such great efforts, in recent decades, to move away from the monolithic authority of the academic expert and to become more inclusive of personal histories recorded and contributed by the public we serve. This openness may make the stories we curate and transmit more relevant and diverse—but not more “true.”

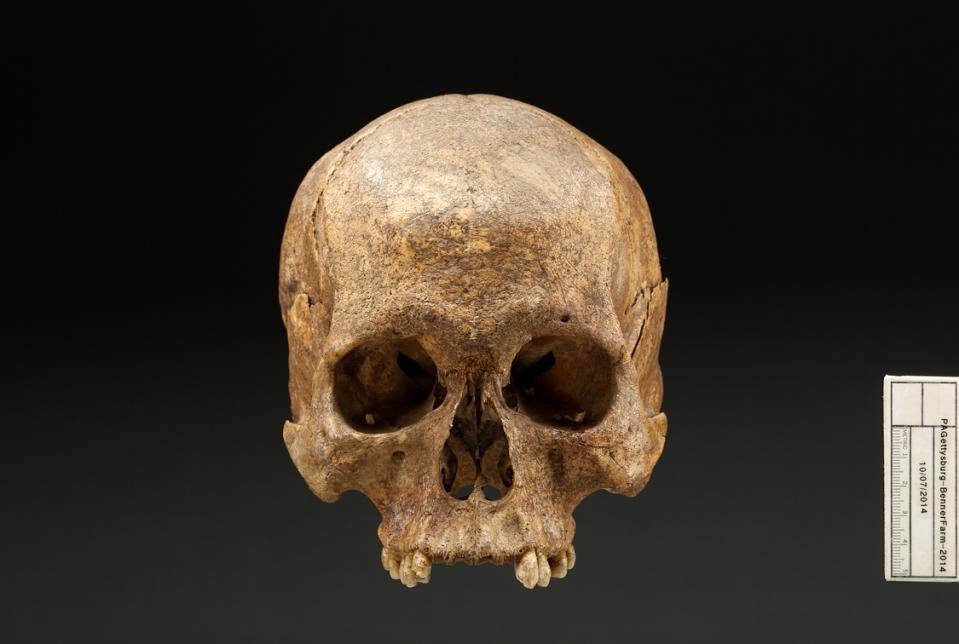

Even documentation may simply enshrine false memories. Take the recent case of the skull of a Civil War soldier put up for auction (skip past the inherent awfulness of that, for a moment). The handwritten label accompanying the skull read “Found at the Benner Farm, Gettysburg, 1949,” and there was notarized documentation attesting that it had been dug up in a garden at the farm. Given that a nearby barn had been pressed into service as a field hospital during the great battle in 1863, conjecture as to the skull’s identity was natural. But the Smithsonian anthropologist who examined the skull after it was pulled from auction (yes, Virginia, there is some decency in the world) saw at a glance it was Native American and far older than 19th century. In fact, he concluded, it was a young Native American man who lived about 700 years ago in Arizona or New Mexico. We will probably never know how this man’s skull ended up in a Virginia field, but it’s clear that without the objective gaze of evidence-based science, he would have ended up in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg.

|

| Frontal view of cranium taken during the Smithsonian Institution’s forensic analysis |

It is tremendously important that we foster a broader and deeper understanding of science and the scientific method. Top-notch science writers like Carl Zimmer, Ed Yong and Robert Krulwich, top-notch science communicators like AMNH’s Neil deGrasse Tyson, may be our best hope for creating an informed public that makes personal choices based on facts, and casts votes based on science. But that same well-informed public, conversant with the slippery nature of truth, memory (and object labels), may be less likely to award museums with their trust on the premise that our objects, and our records, tell an unambiguous story of the past.

Yes, the interpretation of the past will continue to change the understanding of the past and the sanctity of museum information and its objects. Whether from the point of view of new scientific discoveries or from belief systems or just from new evolving understanding, the truth of the past in the museum will continue to be malleable. That more people trust museums in Europe and America today may not apply to other parts of the world, but it does show the level of integrity the institution enjoys due to its development over a long period of time. But for us in Africa where truth does not lie only within the scientific spheres nor within the written records, the museums in our societies may have to bend towards what the communities believe and value in order to get trusted. The scientific truth about the wooden content and age of a cult object in a museum that belies its spiritual potency or relevance cannot not be trusted by an african traditionalist from that cultural background. In the way, the skeletal remains of a Pharao in Cairo museum will not require any scientific detail for a Nigerian muslim to belief both its antiquity and its reality because it was foretold in the quran that the remains of the Pharao will be preserved for the future generations to see and testify. Much as I like what you wrote on this subject, am just thinking of how other people may trust, distrust or doubt the museum facts.

This is exactly why museums need to continue supporting professional work along with public involvement. Memory and history simply are not the same thing. Looking at sources with skepticism and sifting through conflicting accounts have been central tasks for historians. Scientists aren't the only professionals trained to examine evidence, though they may be the only ones considered to have an "objective gaze."

I was so, so relieved to see this post disambiguate the natures of objects (or material culture), the past, history, and memory. Even if it costs museums some of the public's trust, I think it is an inherently right clarification to present and would call for some wonderful collaborations between disciplines within museum staff (natural and social sciences, history, art). It could create a more altruistic environment for visitor and employee alike.