Joan Baldwin is Curator of Special Collections at The Hotchkiss School.

Why is it important?

Because for too long women–and more recently those openly identifying as women–have experienced both hostile and benevolent sexism in the museum workplace. Yes, this is a problem across the board in American workplaces, but for-profit organizations don’t define their mission as all embracing. Shouldn’t museums and heritage organizations do as good a job in terms of work equity as they do in terms of exhibitions and programming?

Every day almost 158 million Americans go to work. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 353,000 of them work in museums or heritage organizations, and of that 353,000, 46.7% are women. That’s a far cry from a century ago when women’s roles in museums were limited, proscribed, and rigidly gendered. Today women hold leadership positions in all but the country’s largest and wealthiest museums. That’s progress, but numbers don’t tell the whole story. Gender is still an unseen problem in museum workplaces.

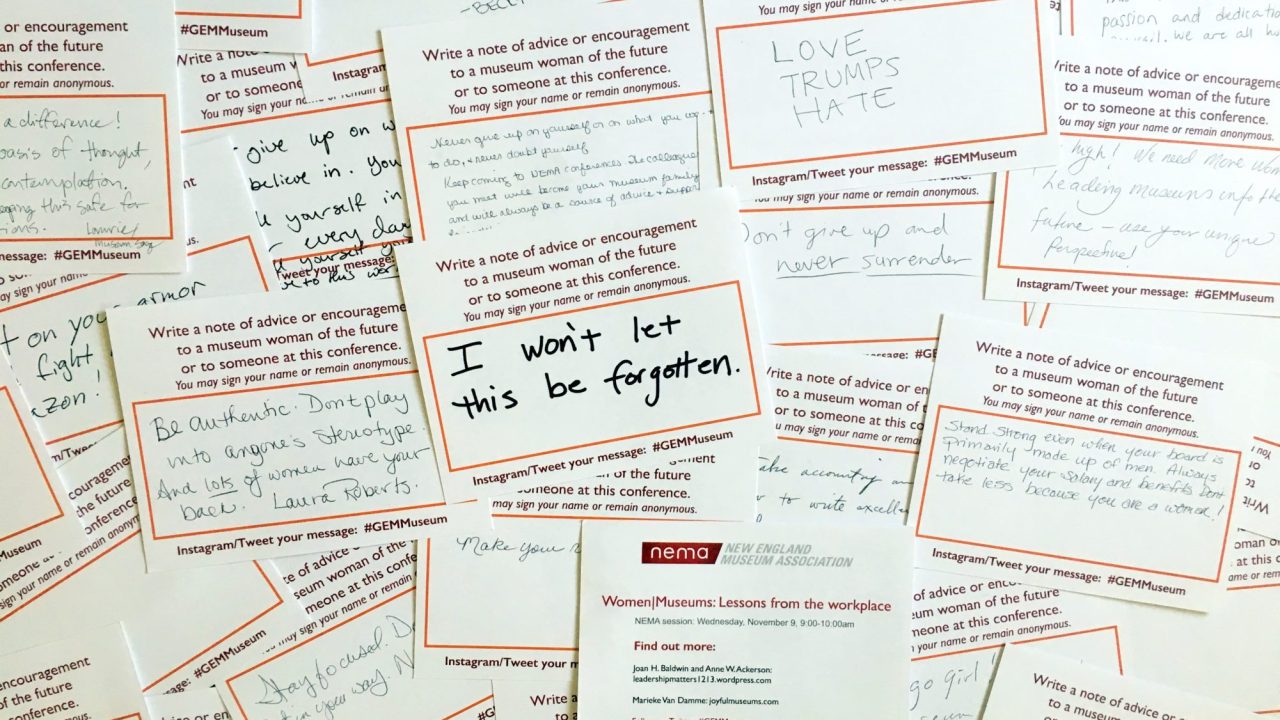

In May 2017, Anne Ackerson and I spoke at AAM’s Annual Meeting on a panel titled “Workplace Confidential: Museum Women Talk Gender Equity.” The panel included four other women, Kaywin Feldman, Wyona Lynch-McWhite, Jessica Phillips, and Ilene Frank. At 8:30 a.m. the room was big, bright and very, very empty. We weren’t worried, figuring we might attract enough audience to fill half the space. We were wrong. More than 150 men and women attended. As moderator, I ended the panel’s remarks early to allow more time for questions. Why is that important? Not because we were charming, smart, witty panelists. We were. But because the audience needed to talk.

At times their questions and comments were heart rending. Women spoke about being cyber bullied, about being shamed for being openly lesbian. They talked about being stalked, and about being raped. While these stories aren’t exclusive to museums or heritage organizations, it is disturbing how issues of gender and bias haunt the museum workplace. In a field so focused on identifying and embracing its community, it is concerning that some museums have one behavior for the public and another for staff. And many of these events have something in common: The women involved often had no one to talk to, nowhere to go, and many were counseled to be silent about their experiences.

In 1973, Susan Stitt formed a group called the Women’s Caucus at AAM’s annual meeting. A year later Stitt and her Caucus returned with a list of demands. Chief among them was a plea to AAM to “draw up guidelines for adoption by AAM concerning fair hiring practices with regard to women.” Almost 50 years later, many of the Caucus’s issues are still problems in the museum workplace. What’s especially disturbing about watching history repeat itself, is that women are at least partly responsible for that lack of change. We have not done enough to help one another. We were not always good mentors and advisors to our sister colleagues. We haven’t always reached out to women of color, to queer and transgender women to help clear a path in a field that is traditional, white, hierarchical, and male. We were so busy doing emotional labor at our various organizations—connecting colleagues, conducting work therapy, making connections in meetings—that we forgot to acknowledge how important we are. As a result, when applying for jobs, too many of us failed to negotiate, landing positions with abysmal salaries because we were so grateful someone wanted us. And that’s on us.

But it’s not all on us. There is a sense that this battle is over, done, and dusted. That, as the percentage of women in the museum field grows, the problems associated with workplace equity in the museum world solve themselves. In fact, one woman told us that gender isn’t the issue anymore. She remarked that the 21st-century’s issue is diversity, not acknowledging that equity is, in fact, part of diversity work. While there is no doubt that lack of racial/ethnic and religious diversity is a key issue in today’s museum workplace, does a woman make a remark like this because implicit bias toward women is so pervasive that we don’t see it anymore, and if it’s brought up, the thought bubble over people’s heads is “ranting feminist”?

Most people in the American workplace recognize expressions of hostile sexism. They are blatantly antagonistic and aggressive. In many museum workplaces, hostile sexism is spelled out in the personnel policy. The trouble is not all museums or heritage organizations have personnel policies as we witnessed in our panel’s Q&A session.

Hostile sexism is one thing. Many of us think we can identify it, and know how our organization deals with it, either through the human resource department or the police. But what about when there is no HR department or when staff is counseled not to report this type of behavior because it’s career damaging? In those cases, women face two choices: daily reminders and confrontation with the colleague in question or quitting their jobs. Many quit. Jennifer Berdahl, who teaches at the University of British Columbia, wrote a paper titled, “The Sexual Harassment of Uppity Women.” Her research suggests that workplace harassment isn’t prompted by sexual desire. Instead, it’s behavior directed at women who violate traditional gender roles, women who are assertive, dominant or deviate from the norm. What does this mean for the diverse museum workplace?

The flip side of hostile sexism is benign or benevolent sexism. President Trump’s compliment to Brigitte Macron is an example. Benevolent sexism comes cloaked in comments that subtly suggest women are not equal to men, meaning their place is to look good but remain subordinate. One woman who spoke during our panel reported an example of benevolent sexism when she described a male colleague telling her she was too pretty to be a lesbian. As a twenty-something employee, she was unprepared to respond to the barb underneath the “compliment.”

You may feel these stories have a tinge of hyperbole. Perhaps this isn’t the working world you’ve experienced. If so, congratulations, but imagine if you will, how these small events of implicit bias multiply, creating a kind of chain that aggregates, affecting both individual behavior and workplace culture. One of the most obvious examples of this is pay equity. A lower salary at the beginning of a career may not seem as important when an applicant is grateful to get a foot in the door. Over time, earning 80-percent of what a heterosexual white man earns, women arrive at retirement almost $450,000 short. And the pay gap figures for women of color are much worse, as are those for queer and transgender women.

So what can the museum field do to change things? It can stop kicking the can down the road. Just because these problems exist in the wider workplace doesn’t mean our field shouldn’t make it a priority to solve them. AAM and the American Association for State & Local History need to set minimum salaries for employment in the museum field and stand behind them. They need to make salary equity a priority. The Accreditation and StEPs programs need to require that museums and heritage organizations have personnel policies, and if they are too small for an HR department, then employees need some alternative that provides HR support. In addition, they should require diversity and equity policies.

As individuals women must be responsible to one another; they must advocate, mentor, and advise one another. And they need to stand up for themselves in ways that are direct, but not overtly hostile. Last, they need to negotiate salaries, benefits, and promotions. Museum workplaces need to do everything they can to make the workplace equitable: work for equitable salaries, take bias out of hiring, be conscious of workplace language and behavior that is offensive, and offer regular gender equity training. And since statistics show women of color and queer women don’t make as much as white women, the museum field needs to become a leader in making sure all women’s salaries are equal, and only then adjusting women’s salaries to meet men’s. And boards and directors, particularly in small organizations, need to understand that size is no excuse for flouting the law. Title VII of the Civil Rights Law doesn’t discriminate.

Museums are wonderful places. They challenge the imagination, provide space for family and friends to interact. They teach, preserve, collect, tell us stories, build community, and so much more. But the time has come for them to be the best workplaces they can be. Women have been part of the museum world almost since its founding as donors, philanthropists, volunteers, curators, educators, and directors. Isn’t it time for the museum workplace to abandon stereotyping and bias? Let’s be the job sector that tackles gender equity.

About the Author

Joan Baldwin is a former museum director. With Anne Ackerson, she is the co-author of Leadership Matters (Alta Mira 2013) and Women in the Museum: Lessons from the Workplace (Routledge 2017). She is the principal writer for the blog Leadership Matters, and a cofounder of Gender Equity in Museums Movement.

This is wonderful, Anne. Another, related, issue, is cultural institutions are often quite small. Even when they aren’t, they often have little or nothing in the way of an HR department and HR and management training. This puts all of us at a disadvantage when it comes to gender discrimination – we so often have no idea what our rights are – and certainly don’t know where to turn when we face problems.

Great article. Thank you for educating me.

Great article!!