Let’s talk about accessibility. In the twenty-first century era of inclusivity, museums are working towards making the visitor experience a more positive and unique one, as part of efforts to increase the number of visitors to museums. In these efforts, issues of accessibility are often overlooked. Not everyone realizes that accessibility is more than just installing ramps and making sure there’s enough room to move freely in the space. If museums truly want to be more inclusive, they need to understand that not everyone who is classified as “disabled” uses a wheelchair, and their needs do not end at physical entry to the building.

For example, some people have trouble hearing. Some people have sensory processing issues. Others have visual impairments, and therefore have trouble navigating even everyday life sometimes. It is this last group that I will focus on. People with visual impairments deserve to have a unique museum experience just as much as the average person, and the technologies being developed for them to navigate everyday life can also be used in the museum to help with that. And even though these technologies are made for the visually impaired, everyone can benefit from their use in museums.

My mother became legally blind a few years ago after being diagnosed with a form of macular degeneration. She took it surprisingly well, from my perspective, but it made me think. I always loved going places with her, including museums. My chosen profession is museum work, and being close with my mom, I want her to be involved. When I started graduate school, we had several lectures about accessibility in museums, and given my personal connection, I chose to write my thesis about the visually impaired in museums. This article is a modified version of that thesis—who better to help me generate ideas than my own mother?

And so, I took her along with me to visit three exhibitions at three different museums, and told her to give me her impression of each of them and her opinions on the overall experience.

Exhibit 1: An art museum

The art museum we went to was going through an extensive renovation at the time of our visit, so the experience of navigating the museum space has likely improved overall since then. That being said, one thing renovations can’t fix is the availability and quality of audio tour equipment. When we first entered the museum, we were given some seemingly understandable instructions on how to get to the exhibition we wanted to see. I say “seemingly understandable” because as a sighted person, I was able to figure out which direction to go and where to climb the stairs, etc. My mother made it there with my help; if she had been by herself, it might have been a bit difficult to locate the exhibition (even with the remaining vision she has, as the exhibition itself was in a small part of the gallery).

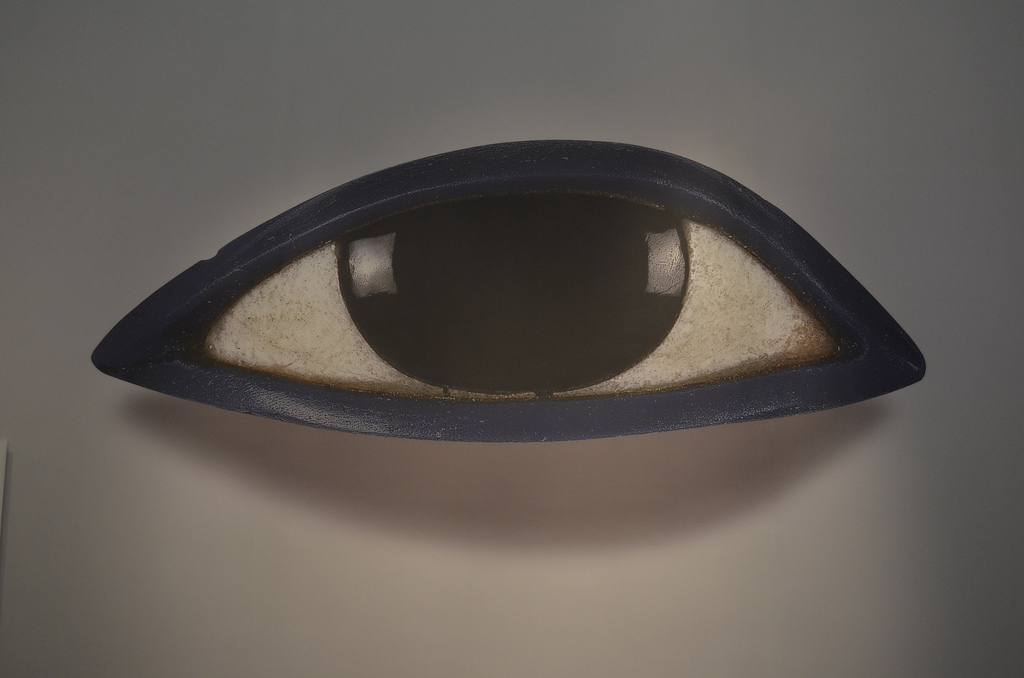

The exhibition was a small one, featuring art from ancient Egypt (fascinating and very beautiful works). It took up a small corridor, with the objects mounted in cases on the walls. The introductory label was informative, and presented in a large enough print so that my mother might have been able to read it, if not for the lighting (artificial lights hurt her eyes, and if they are too dim then reading is almost impossible, regardless of font size). I had to do most of the label reading and object description for her. Once we had gone through the space, I returned to the entrance and asked the person at the front desk what kind of audio tour they had available. They proceeded to show me a device that looked like it had emerged from a time capsule sealed in 1995—it was an actual CD player, a chunky box the size of a handbag. This was the only one available, too. There were no other copies, and no other devices for visitor use. Needless to say, I was surprised.

The employee behind the counter implied that this device would be replaced with the upcoming renovations (I unfortunately have not been back since, but I hope that is true), and also informed me that there would be an upcoming docent training session specifically targeted for visually impaired visitors. Docent training is great, and will definitely help to improve the visitor experience. However, many visitor studies indicate that there are different types of visitors with divergent needs and interests, and this is no different for those with visual impairments. Not everyone who visits a museum is interested in a guided tour. So what’s the solution in that case? I thought of a few options:

Solution 1: Better/more modern audio tour devices

For those visitors who prefer navigating a museum on their own, but still want more information than what’s on the labels, audio guides are the happy medium. Many museums have fantastic audio tours and digital guides available, but not everyone who visits knows about them. Perhaps better advertising of the tour is the key to making them more accessible. Another way is to update the technological medium that presents the tour. There are several companies today that specialize in creating digital content, and many museums are open to forming partnerships with them. What needs to be addressed while creating this content, of course, is accessibility. While digital content and audio tours are a great way for a visually impaired person to learn about the objects in a museum, it can still seem very detached if all they are doing is listening to someone talk about an object without a clear understanding of what the object is.

Solution 2: The Aipoly app

A start-up based in Melbourne, Australia, called Aipoly has developed an app that uses image recognition software to help people identify objects in the space around them. The app (called Aipoly Vision) uses the smartphone’s camera to record objects within its view and tells the phone’s owner what they are looking at. On their website they explain how the Aipoly Vision app is made specifically for the visually impaired. Since they are open to collaboration, this seems like a great opportunity for museums to have an easily accessible tool for visually impaired visitors to use. The best part is that it doesn’t need an internet connection to work!

Exhibit 2: A natural history museum

The dinosaur fossil exhibition at the natural history museum we visited is also undergoing a renovation in preparation for its reopening in the next year. We visited the temporary exhibition there, and since the museum is pretty popular, it was unsurprisingly crowded. This didn’t make it too difficult to navigate though, as the museum is used to accommodating large numbers.

The wall paneling and some other labels were much easier for my mother to read, which was a big plus. Some labels were smaller than others, but that’s understandable given the exhibition content: dinosaur fossils. I was also looking out for interactive elements, because natural history museums have the best potential for them after science centers, and interactives that engage multiple senses go a long way toward accessibility and inclusivity. For that reason, I was pleased to see a display of a pair of triceratops tusks that visitors were allowed to touch. This was the only interactive part of the exhibition though, which was a little disappointing. I realize this exhibition is temporary, so interactives are not really an option—but I hope when the new permanent one is complete there are more interactive displays available. Otherwise it seems like a huge missed opportunity.

Solution 1: Haptics

A great way to make interactive displays and features in a natural history museum (or any history museum) is with something called haptics:

“…the science of applying touch (tactile) sensation and control to interaction with computer applications…By using special input/output devices (joysticks, data gloves, or other devices), users can receive feedback from computer applications in the form of felt sensations in the hand or other parts of the body. In combination with a visual display, haptics technology can be used to train people for tasks requiring hand-eye coordination, such as surgery and spaceship maneuvers. It can also be used for games in which you feel as well as see your interactions with images.” –WhatIs.com

Haptics is already in use in some universities and museums, and is also a great tool for conservators. Allowing someone to “touch” an object without having to remove it from collections storage can not only enhance the experience for the visitor, but also give new life to an object otherwise unavailable for display. It essentially works by using touch sensors hooked up to a computer. When the computer recognizes that you are close enough to the object, it sends vibrations to the handheld component to produce the illusion of actual touch (for more information, check out this link).

Solution 2: 3D Printing

We likely have all heard of 3D printing. The printers themselves sell in small models at places like bookstores and electronic retail stores. You also may have heard that they have been used successfully in some art museums to create replicas of artwork for people to touch. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has made successful use of this technology by allowing artists and visitors to make their own copies of artworks on display at the museum, and exhibiting the artists’ new work made with the printed copies. The Art Institute of Chicago also uses 3D printed copies from their collection to aid in the curriculum for their design students. This success in art museums is easily transferrable to history and science museums—if a 3D replica can be made of a painting or sculpture, why not a fossil? An artifact? Pretty much anything can be made with a 3D printer. So why aren’t more museums jumping on the 3D bandwagon? The short answer is budget and copyright issues.

Exhibit 3: An aerospace museum

The aerospace museum we went to is massively popular, with an impressive size and atmosphere. Given the size of the museum and the interactive nature of many of the exhibitions, you would think it would be easier for a visually impaired person to enjoy the overall experience.

The interactives and displays were great, and my mother commented after our visit that this was definitely her favorite of the three exhibitions we went to. The problem, though, was navigating it. One of the interactives involved a motion sensor and a giant screen, and so it took up a considerable amount of floor space within the first part of the exhibition. The interactive itself was pretty fun (mimicking the flight patterns of birds) but put a person in every available spot on the floor, and others would have to walk through the interactive to make it to the rest of the displays. My mother said as much as we made our way through the space; she immediately commented on how she would be confused if she saw people standing in the middle of the room, having not noticed the bird silhouettes outlined on the floor.

Perhaps if a different section of the museum was dedicated to this exhibition, it might have made up for this issue—the museum of course has several exhibition spaces of various sizes—but given that this was another temporary exhibition, that is not always an option. So how can museums rectify this?

Solution 1: “Wearable technology”

If my mother had gone to this exhibition by herself, there would have been a greater chance of her being injured, or bumping into objects and other people. This is a problem visually impaired people face all the time in their daily lives, regardless of where they are. Guide dogs and white canes are the norm for helping with this issue, but not everyone can afford or accommodate a guide dog, and while canes are useful for helping to avoid obstacles, they fall short in allowing the user to discern what’s around them. They are also not practical for use in certain places (my mother doesn’t always use hers if we’re at a place like the supermarket where there is already limited walking space).

Enter “wearable technology.” Car company Toyota is developing prototypes for devices that visually impaired people can use to know more about what’s around them. Called Project BLAID, the device is mounted on the shoulders and includes a camera that records images of the wearer’s surroundings. It speaks to the wearer and tells them how far away something is, and how long it would take for them to get to that spot. The technology is similar to what Toyota uses in some of their car models. This could be adapted for use in museums to accompany an audio tour.

Solution 2: Universal Design

One major way some of these problems can be minimized (or eliminated entirely) is if we consider them from the beginning. During the initial exhibition design, we can use Universal Design principals to better incorporate inclusivity. Dr. Sheryl Burgstahler of the University of Washington sums it up best:

“When UD principles are applied, products and environments meet the needs of potential users with a wide variety of characteristics. Disability is just one of many characteristics that an individual might possess. For example, one person could be Hispanic, six feet tall, male, thirty years old, an excellent reader, primarily a visual learner, and deaf. All of these characteristics, including his deafness, should be considered when developing a product or environment he, as well as individuals with many other characteristics, might use.” (Emphasis added.)

Dr. Burgstahler is the founder and director of DO-IT (Disabilities, Opportunities, Internet-working, and Technology) at the University of Washington. I have included her article outlining Universal Design Principals in my list of further reading.

Final Thoughts

Obviously, the biggest roadblock to adopting these technologies is budget. Not every museum has money they can magically draw out of a hat to pay for these things. This is where grants come into play. Many foundations and other grant-giving institutions specialize in funding for technology, and they are great places to reach out for this. Additionally, loan policies don’t have to apply exclusively to collections objects; if a museum has extra resources they can provide to another museum, a long-term loan agreement can be reached so the technology can reach as many people as possible. The groups that make the technologies can also partner with museums, which is not unheard of in modern times.

In our current world of increasing inclusivity, we can’t afford to ignore accessibility. This means that we must also acknowledge developments in technology outside the museum field, and use them to our advantage wherever necessary. Using new technology to help those who can’t see not only enhances their museum experience, but can also allow sighted people to look at museum exhibitions in a new way (pun intended).

About the author:

Samantha Silverberg is an emerging museum professional living in Northern Virginia. She worked on this issue of accessibility for the visually impaired for her thesis at Arizona State University, where she earned her Master of Arts degree in Museum Studies in 2016. Accessibility is an important issue for her, as her mother is a person with a visual impairment, and she looks to advocate for better learning environments for everyone.

Further Reading

Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, as Amended

“Universal Design Process Principals and Applications” by Dr. Sherry Burghstahler

“How Haptic Technology Works” by William Harris

“App Spots Objects for the Visually Impaired” by Rachel Metz

“Haptic Interactive Technology Brings Visitors Closer to Museum Collections” from Museums and Heritage Advisor

“Please Feel the Museum: The Emergence of 3D Printing and Scanning” by Liz Neely and Miriam Langer

“Project BLAID: Toyota’s Contribution to Indoor Navigation for the Blind” by Jamie Pauls

“What is Haptics?” from whatis.com

“Haptic and Tactile Museum Experience” from Zero Project

Hello! We are working for making our museum accessible, I’d like to speak to the author directly if possible? Thank you!