Exhibition labels are a primary tool museums use to communicate with visitors, so every word (and punctuation mark!) counts.

To underscore this, AAM’s Curators Committee sponsors a yearly competition spotlighting the work of outstanding label writers and editors. CurCom leads the Excellence in Exhibition Label Writing Competition in cooperation with the EdCom and NAME networks and in partnership with the Museology Graduate Program at the University of Washington, Seattle.

The jurors for this year’s awards were the label writers Swarupa Anila, Bonnie Wallace, Michael Rigsby, and Emilie S. Arnold. Presented with 240 submissions, from a diverse range of museums around the world, they selected eleven winners. Read the winning labels below, and see the full announcement for statements from the winners and notes of praise from the jurors.

1. “Keeping Clean on a Diesel Submarine”

From A View from the Deep: The Submarine Growler & The Cold War; Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum; New York, NY

Jessica Williams, writer; Alex Wellerstein, writer; Adrienne Johnson, editor

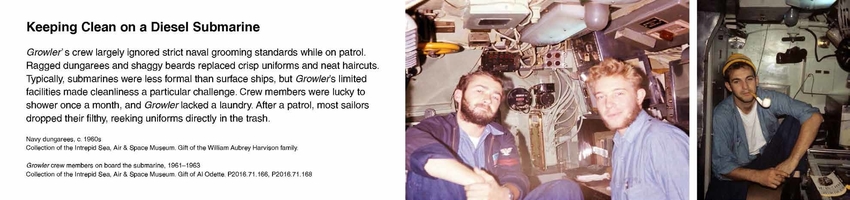

Keeping Clean on a Diesel Submarine

Growler’s crew largely ignored strict naval grooming standards while on patrol. Ragged dungarees and shaggy beards replaced crisp uniforms and neat haircuts. Typically, submarines were less formal than surface ships, but Growler’s limited facilities made cleanliness a particular challenge. Crew members were lucky to shower once a month, and Growler lacked a laundry. After a patrol, most sailors dropped their filthy, reeking uniforms directly in the trash.

Navy dungarees, c. 1960s

Collection of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum.

Gift of the William Aubrey Harvison family.

Growler crew members on board the submarine, 1961–1963

Collection of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum. Gift of Al Odette.

P2016.71.166, P2016.71.168

2. “President Kennedy is Shot”

From A View from the Deep: The Submarine Growler & The Cold War; Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum; New York, NY

Jessica Williams, writer; Alex Wellerstein, writer; Adrienne Johnson, editor

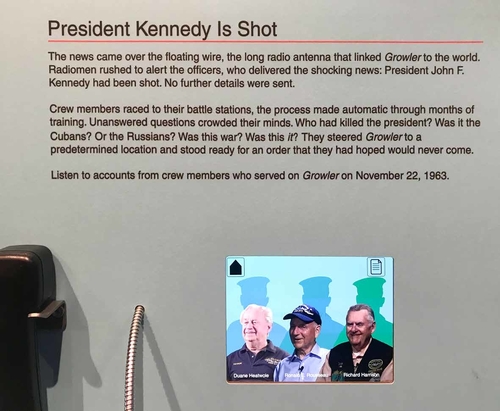

President Kennedy is Shot

The news came over the floating wire, the long radio antenna that linked Growler to the world. Radiomen rushed to alert the officers, who delivered the shocking news: President John F. Kennedy had been shot. No further details were sent.

Crew members raced to their battle stations, the process made automatic through months of training. Unanswered questions crowded their minds. Who had killed the president? Was it the Cubans? Or the Russians? Was this war? Was this it? They steered Growler to a predetermined location and stood ready for an order that they had hoped would never come.

Listen to accounts from crew members who served on Growler on November 22, 1963.

3. “Segregated drinking fountains in the county courthouse in Albany, Georgia, 1962”

From Danny Lyon: Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement; Delaware Art Museum; Wilmington, DE

Ashley SK Davis, writer; TAHIRA, writer; Melva Ware, writer; Amelia Wiggins, editor; Heather Campbell Coyle, editor

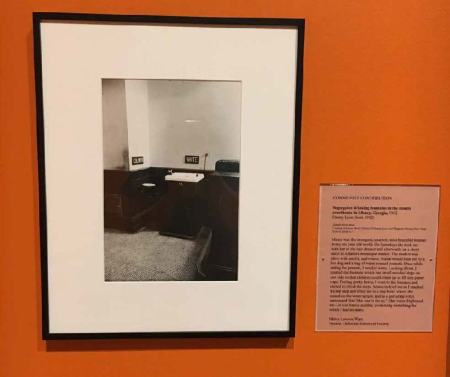

COMMUNITY CONTRIBUTION

Segregated drinking fountains in the county courthouse in Albany, Georgia, 1962

Danny Lyon (born 1942)

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery © Danny Lyon and Magnum Photos, New York

DAM L-2018-4.7

Mame was the strongest, smartest most beautiful woman in my six year old world. On Saturdays she took me with her to the hair dresser and afterwards on a short stroll to Atlanta’s municipal market. The market was alive with smells, and voices. Mame would treat me to a hot dog and a bag of warm roasted peanuts. Once while eating the peanuts, I needed water. Looking about, I spotted the fountain which had small wooded steps on one side so that children could climb up to fill tiny paper cups. Feeling pretty brave, I went to the fountain and started to climb the steps. Mame tackled me as I reached the top step and lifted me to a tiny bowl where she turned on the water spigot, and in a quivering voice announced that “this one is for us.” Her voice frightened me—it was barely audible, awakening something for which I had no name.

Melva Lawson Ware

Trustee, Delaware Historical Society

4. “Mixed Up and Recombined”

From Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World; National Museum of Natural History; Washington, DC

Angela Roberts, writer; Laura Donnelly-Smith, editor

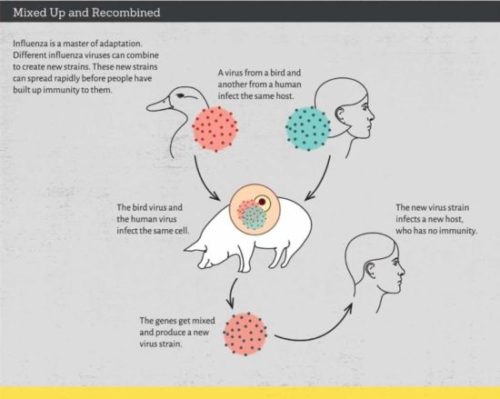

Mixed Up and Recombined

Influenza is a master of adaptation. Different influenza viruses can combine to create new strains. These new strains can spread rapidly before people have built up immunity to them.

A virus from a bird and another from a human infect the same host.

The bird virus and the human virus infect the same cell.

The genes get mixed and produce a new virus strain.

The new virus strain infects a new host, who has no immunity.

5. “Scientists say the way jellies move through water…”

From Underwater Beauty; John G. Shedd Aquarium; Chicago, IL

Ashleigh Braggs, writer; Nancy Goodman, writer; Judy Rand, editor/writer

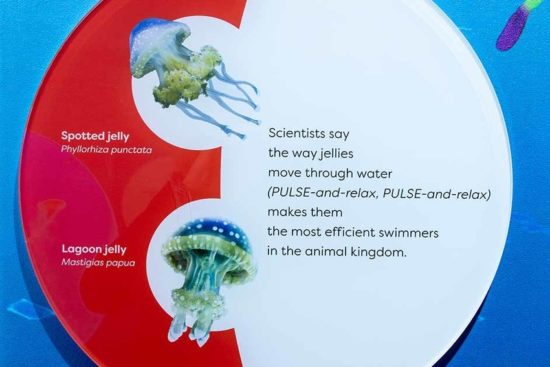

Scientists say

the way jellies

move through water

(PULSE-and-relax, PULSE-and-relax)

makes them

the most efficient swimmers

in the animal kingdom.

Spotted jelly

Phyllorhiza punctata

Lagoon jelly

Mastigias papua

6. “Why did the artist paint her this way?”

From “Modern Times: American Art 1910-1950,” in conjunction with “Art Splash: Bright Lights, Little City;” Philadelphia Museum of Art; Philadelphia, PA

Liz Yohlin Baill, writer; 3rd grade students at Friends Select School, writers; 5th grade students at Masterman Elementary School, writers; Amy Hewitt, editor

Why did the artist paint her this way?

This is March, the artist’s 12-year-old daughter. Her dad decided to leave her face blank.

_________

Kid’s Take

Did he do it by accident? Can he just not draw faces?

—Gianna

I think he did that to show that she does not need a pretty face to be amazing.

—Pelham

7. “Imagine a life spent entirely in water…”

From Underwater Beauty; John G. Shedd Aquarium; Chicago, IL

Ashleigh Braggs, writer; Nancy Goodman, writer; Judy Rand, editor/writer

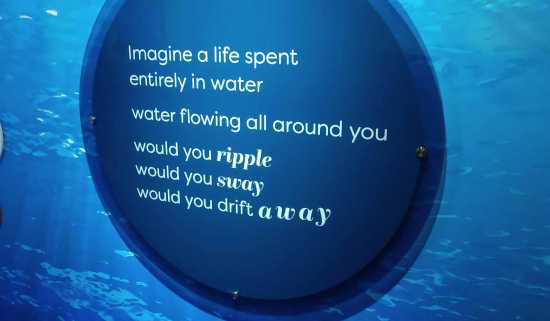

Imagine a life spent

entirely in water

water flowing all around you

would you ripple

would you sway

would you drift a w a y

8. “Jim Crow: South”

From Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow; New-York Historical Society; New York, NY

Marjorie Waters, writer; Marci Reaven, editor

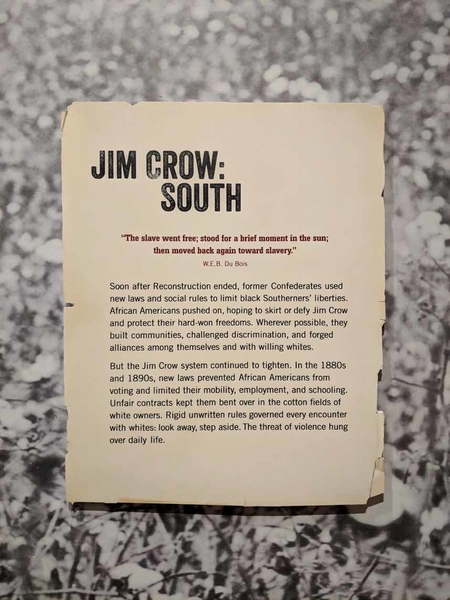

JIM CROW: SOUTH

“The slave went free; stood for a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.”

–W.E.B. Du Bois

Soon after Reconstruction ended, former Confederates used new laws and social rules to limit black Southerners’ liberties. African Americans pushed on, hoping to skirt or defy Jim Crow and protect their hard-won freedoms. Wherever possible, they built communities, challenged discrimination, and forged alliances among themselves and with willing whites.

But the Jim Crow system continued to tighten. In the 1880s and 1890s, new laws prevented African Americans from voting and limited their mobility, employment, and schooling. Unfair contracts kept them bent over in the cotton fields of white owners. Rigid unwritten rules governed every encounter with whites: look away, step aside. The threat of violence hung over daily life.

9. “Atlanta, police car window, 1963”

From Danny Lyon: Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement; Delaware Art Museum; Wilmington, DE

Ashley SK Davis, writer; TAHIRA, writer; Melva Ware, writer; Amelia Wiggins, editor; Heather Campbell Coyle, editor

COMMUNITY CONTRIBUTION

Atlanta, police car window, 1963

Danny Lyon (born 1942)

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery © Danny Lyon and Magnum

Photos, New York

DAM L-2018-4.31

My home from birth to age 22 was directly across the street from a police station. As small child in 1960s, I remember hearing calls come out over the police car radio, “Seeking male, black 18 to 25, wearing dungarees and white tee shirt.” It was description that fit every young man in our neighborhood, including my two big brothers. It was a call that meant the police would be rounding up our men indiscriminately and, in many cases, physically assaulting them for all the neighborhood to see. So, when I would hear that radio call, I did what my parents trained me to do, holla down the street, “Stephen and Gerald get in the house!”

TAHIRA

Storyteller and Musician

10. “H is for Home”

From Intrepid A to Z; Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum; New York, NY

Jessica Williams, writer; Adrienne Johnson, editor

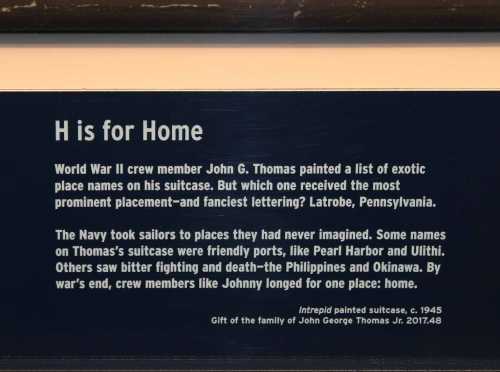

H is for Home

World War II crew member John G. Thomas painted a list of exotic place names on his suitcase. But which one received the most prominent placement—and fanciest lettering? Latrobe, Pennsylvania.

The Navy took sailors to places they had never imagined. Some names on Thomas’s suitcase were friendly ports, like Pearl Harbor and Ulithi. Others saw bitter fighting and death—the Philippines and Okinawa. By war’s end, crew members like Johnny longed for one place: home.

Intrepid painted suitcase, c. 1945

Gift of the family of John George Thomas Jr. 2017.48

11. “Reckoning”

From T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America; Peabody Essex Museum; Salem, MA

Karen Kramer, writer; Rachel Allen, writer; Bridget Devlin, writer; Rebecca Bednarz, editor

RECKONING

Cannon’s work is a powerful reclamation of America as indigenous country.

We are standing on the contested grounds of America. The land below us belonged to the indigenous Naumkeag community long before settlers claimed it as Salem and longer still before Columbus “discovered” the so-called New World. A wave of destruction followed his arrival: war, disease, land-hungry colonists, and hundreds of years of federal policies nearly wiped out Native populations across the United States. Emerging during the anti-war protests and civil rights movement of the 1960s, Cannon interrogates these troubling aspects of America’s histories. He urges us to grapple with the contradictions and questions of history—and our place in it.

Why Did He Paint Her Like That? Is My Favorite.